environment music: garbage George Ward Killooleet Pete Seeger

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

I Learned This Song in Summer Camp…

…a camp which was, not coincidentally, run by Pete’s elder brother John Seeger, who died just about a month ago at age 95. At Camp Killooleet, community singing was a regular feature, and one of the musicians who led the kids was a guy named George Ward. I learned this song from hearing him sing it.

Here’s Pete Seeger doing it.

Education Indian music music: muscle training practice rhythmic cycles riyaaz tabla

by Warren

9 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Practicing Inside Rhythmic Cycles

One of the most challenging areas for many students of Hindustani music is working within rhythmic cycles. The ready availability of tabla machines has not solved this problem, because the core issue has more to do with not knowing how to practice than with not having a tabla player available all the time.

It is helpful to spend some time analyzing the various components of rhythmic-cycle practice. Once a singer begins this work, the cognitive load goes waaaaaay up; a lot more brain cells are required to keep all the elements of the musical equation under control. While holistic, gestalt-oriented practice is a must, it can be very helpful to break things down into smaller components and approach them with reductionistic ruthlessness.

To be competent in rhythmic-cycle-based improvisation, a singer must:

1 – be able to process rhythmic information concurrently with intonational information. That is to say, you have to be able to hear and feel the beats without getting distracted by them to the point that you go out of tune.

2 – be able to recognize important beats in the cycle and recalibrate according to position. That is, you have to hear crucial structural points and have enough cognitive strength available to lengthen or shorten your melodic line if necessary.

3 – be able to make coherent melodic shapes of specific lengths. In performance, it’s not enough to start an improvised melody at a specific point in the rhythm and finish it at another point — the melody you’re making needs to make sense. And (as if that weren’t enough) it needs to make sense at several levels; it has to be correct in raga terms, and it has to have gestural integrity. Those two are emphatically not the same thing.

Let’s take those distinct skills in turn, and I’ll discuss some ways of approaching them in the course of your practice.

India Indian music music: 78s old masters Ramakrishnabua Vaze

by Warren

1 comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

More Music from Ramakrishnabua Vaze

Here are three more of the classic 78 rpm discs recorded by Pandit Ramakrishna Vaze (1871 – 1945). At some point soon I will post the long version of his Miyan ki Malhar, a classic recording from the AIR archives; it’s longer than the maximum allowed by YouTube, so I’ll be using Vimeo for that one.

The complex compound raga Khat

Deodhar tells some amusing stories of Vazebua’s eccentricity:

“In 1927 I requested Buwasaheb to pay a visit to my music school. He appeared in a loose shirt and haphazardly torn cap…Some of our boys and girls sang for him. After this I requested him to say a few words to the students. He started his address with these words, ‘I am a simple person. I do not like to dress up. I have a jacket — I even wear it sometimes. I say, Mr. Deodhar, come to my house and I shall show you my jacket. Very beautiful material. One cannot acquire learning by putting on fine clothes — can one now?’ Some of our girls could not help laughing at this. They put their hankies to their lips and giggled. I felt embarrassed. IN an attempt to change the subject I told Buwasaheb that our students were anxious to hear him sing…He duly appeared at the school as promised, and sang beautifully for our students.

(snip)

“Shri Korgavkar…decided to start a harmonium class in Belgaum…he sent a most courteous invitation to Vazebuwa to preside over the inauguration function. Vazebuwa agreed….Buwasaheb was requested to give his presidential address. Buwasaheb stood up. The audience was all attention. Buwasaheb started, ‘Friends…friends.’ But he was at a loss to find anything more to say. After an embarrassingly long silence he said, ‘Nothing…nothing,’ and sat down. After repeated clamour from the audience and entreaties from the organizers, Buwasaheb once again stood up and continued his speech, ‘Ladies and Gentlemen! Today we are inaugurating this harmonium class. This instrument is known as a harmonium. We call it bend-baja (a derogatory term usually associated with a mouth-organ). So from today anyone who wants to learn to play bend-baja can do so.’

B.R. Deodhar: “Pillars of Hindustani Music,” pp. 128-130

India Indian music music: Amir Khan genius

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Ustad Amir Khan

Because everybody should fall in love with a voice, and Amir Khan’s has filled my ears for over three decades now.

Raga Malkauns

Raga Todi

Raga Yaman

Jazz music: jazz vocals Mildred Bailey

by Warren

2 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Bessie Smith’s Overtones: Everybody Should Enjoy Mildred Bailey Every So Often

I acquired Henry Pleasants’ wonderful book, “The Great American Popular Singers” at Manny’s Books in Pune, where it rested, long-ignored, on a small shelf with other publications about Western music. The books on Indian music were in another section of the store; the only customer who went routinely to both shelves was me. I bought the book and began reading it in the rickshaw to Deccan Gymkhana. By the time I got home I’d learned things I never knew about Bessie Smith, Al Jolson and Bing Crosby (all of whom I’d heard, and heard of), and about Mildred Bailey, an unfamiliar name. Pleasants rhapsodized about her musicality, whetting my appetite.

Opportunities in India to hear Mildred Bailey’s music were nonexistent….so it wasn’t until a couple of years later that I found a 10″ lp in the collection of my friend Gene Nichols, and taped it for my own enjoyment.

And enjoyment was definitely what resulted. Bailey’s pitch, her sense of swing, her deceptive melodic simplicity, the subtlety of her ornamentation and phrasing…she sounded like a trumpet, or an alto saxophone.

Leonard Feather: “Where earlier white singers with pretensions to a jazz identification had captured only the surface qualities of the Negro styles, Mildred contrived to invest her thin, high-pitched voice with a vibrato, an easy sense of jazz phrasing that might almost have been Bessie Smith’s overtones.”

(Feather — The Book of Jazz)

Or, as Leonard Feather says, like Bessie Smith’s overtones.

Thanks for the Memories

India Indian music music photoblogging: Amjad Ali Khan Hindustani instrumentalists Shahid Parvez Shivkumar Sharma Sultan Khan Zakir Hussain Zarin Daruwalla

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Hindustani Instrumental Photoblogging

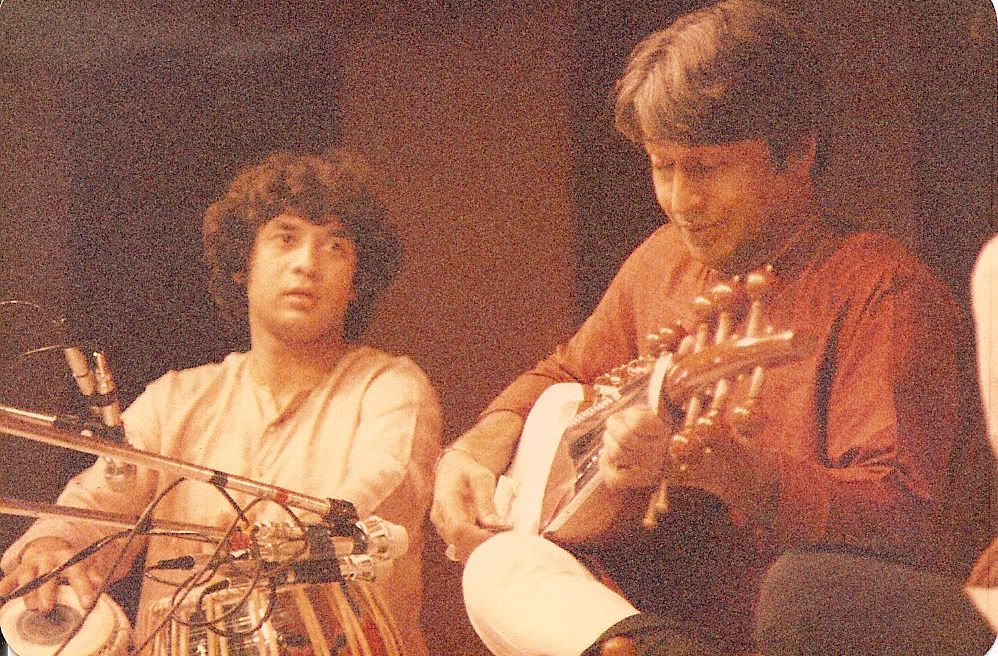

As part of my continuing drive to provide visual, auditory and intellectual content, here is an assortment of the photographs I took of Hindustani instrumentalists during the 1980s. Zakir was performing a great deal in Pune during that time, and I got many good images of him.

Amjad Ali Khan and Zakir Hussain. Sawai Gandharva Mahotsaav, Pune, 1985

India Indian music music: genius Jaipur Gharana Kesarbai Kerkar khyal

by Warren

10 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Kesarbai Kerkar’s Music Is, In Fact, Out Of This World.

One of the greatest voices of the twentieth century belonged to Kesarbai Kerkar, the legendary singer of Jaipur-Atrauli tradition, who bestrode the narrow concert platforms of India like a colossus until a few years before her death in 1977. To listen to Kesarbai is to experience intellectual, emotional and artistic depth in a way that can hardly be matched anywhere else.

Nat Kamod

Jazz music Warren's music: Chazz Rook Jazz Composers Alliance Orchestra Mingus

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Chazz’ Mingus Story: A Composition for Jazz Orchestra and Two Speaking Voices

I write music for the 20-piece big band run by Boston’s Jazz Composers’ Alliance. The JCA Orchestra does several concerts a year (recently we’ve had some Sunday club dates at Johnny D’s, in Somerville, MA, which is really a blast), always featuring writing by all the composers in the collective. I am one among many, the seniormost being the Alliance’s founder, Darrell Katz. You can find out more about the Jazz Composers Alliance here.

In 2007 we decided to present a “tribute concert,” where we’d undertake to give our impressions of the music of three important jazz composers: Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, and Charles Mingus. After some dithering, I decided to develop a piece on Mingus. Notice the preposition. I did not want to do an arrangement of a Mingus tune; while I enjoy arranging other people’s music, I had an idea in mind.

One of my oldest friends is a sarod player, an American whom I met in the early years of my study of Indian music. His given name was Charles Rook, but he was known to one and all as “Chazz.” When I asked him how he’d gotten the name, he told me a long and amazing story about his relationship with the great bassist and composer. Since that time (in the mid-70s) I’d heard him tell it over and over, and I’d had it told to me by other mutual friends (“You know Chazz’ story about Charlie Mingus? No? Well…”). So I knew the outline pretty well.

Chazz Rook, visiting Pune in 1987

India Indian music music photoblogging: Dagar brothers dhrupad

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

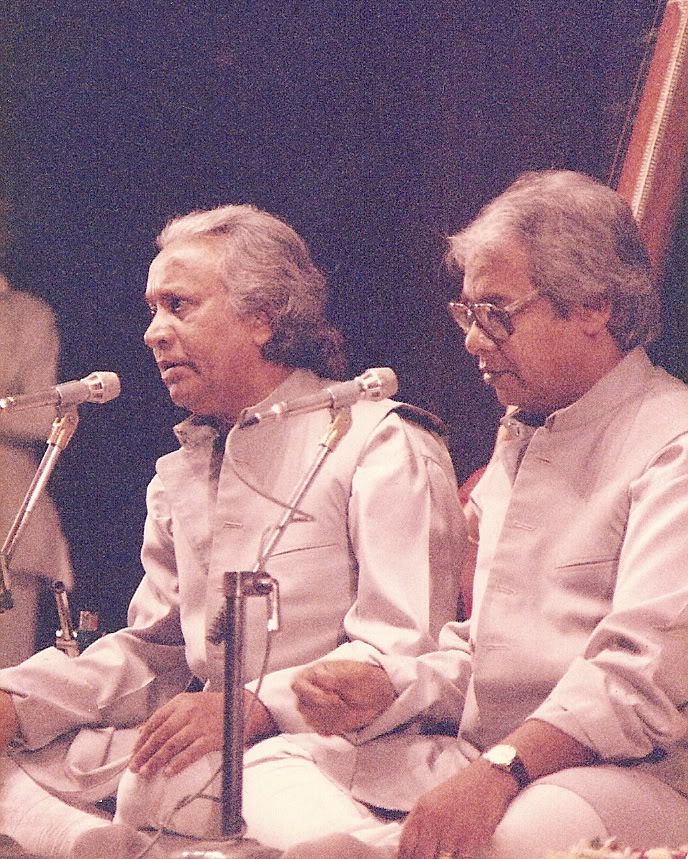

Dagar Photoblogging: Pune, 1985

These photographs were taken at a Dhrupad Sammelan in Pune, late in 1985. These are Zahiruddin and Faiyazuddin Dagar, the “Younger Dagar Brothers.”

Zahiruddin (L) and Faiyazuddin Dagar.

Education music: music learning practice riyaaz

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Two Techniques for Regulating Your Practice

More from the Brian O’Neill Interview. This post has the two of us discussing two techniques for controlling the use of practice time to maximize ROI.

The Technique of a Hundred Beans

WS: Here is a very good technique that my teacher showed me for helping to regulate one’s practice: Get two bowls, or cups, and, from the supermarket buy a bag of kidney beans or garbanzo beans or something. Garbanzos are good for this. Count out a hundred of them. Put them in one bowl. Transfer one bean from the source bowl to the target bowl after each repetition of the line.

Later, I introduced a refinement. You see, you take one lick and you repeat it exactly a hundred times. My refinement was that sometimes in those bags of garbanzo beans you get one that’s misshapen or miscolored or something. I put that one in there, and whenever I got that one, I improvised for the same length of time. So at some point, I’d get a little vacation, and it was always a pleasant surprise.

BTO: What’s the unit of time per garbanzo bean?

WS: It was one lick, whatever the lick was — you know, typically not more than a minute. A hundred minutes is a long time!

BTO: Oh, each repetition?

WS: Yeah, each repetition. Finish a repetition, transfer a bean — This is the way to really regulate repetition.

If you don’t repeat it, then you wind up thinking that you know it, but not really having it there when you need it. It’s gotta be like tying your shoes, you know? It has to be completely fixed in muscle memory.

Index Cards

One way of handling the question of “what should I practice today?” is to get some index cards. On each card you jot down the nature of a particular practice, along with a stipulated length of time — however long that particular practice is going to last.

“Expanding & contracting, going up six notes and going down, and then doing that from the tonic, third and fifth of the natural minor scale.” 10 minutes

“Four-note paltas in Raga Kafi, from Mandra Pa to Tar Ma.” 20 minutes.

“Major 7, Dom 7, Minor 7 and Min7 b5 arpeggios in all twelve keys, through the cycle of fifths.” 25 minutes.

“Sightreading from Captain O’Neill’s book of fiddle tunes.”10 minutes.

“This specific piece of complex bol-bant in ‘Piyu pal na laagi mori ankhiyaa’ (Raga Gaud Sarang).”15 minutes.

“Fast scales in 16th note triplets across a two octave range, sung & played on guitar. 20 minutes. Starting at metronome thus-and-such, going up to at least metronome thus-and-such.”

And, so, every time that you invent a new practice, you note down what it is. Then, after a little while, you wind up with a batch of cards; you have, perhaps, 15 or 20 cards.

Then, after you’ve done your basic warm-ups, you shuffle the cards, and whatever comes up, you do that. And then your practice for the day is however many cards you can fit in the unit of time that you have allotted to practice. And then, here’s the nice part: the next day, you don’t just start where you left off — you shuffle the cards again.

Which means that some of the time you wind up doing the same practice three days in a row. But over all, over the space of, say, two weeks, you wind up meeting everything in there, and experiencing it as a sort of total repertoire of stuff to do. Then you may observe, in the course of those practices, “Huh, it really seems like in this part of this thing [= practice, card], I’m really not making it.” Then you design a lick that embodies that particular [problematic] thing, and that’s when you do the technique-building, metronome-incrementing practice (described in “One Lick for Two Hours.” Then you go back to that same practice [on the index card] next week or something, and you’ll ace it!