Education Indian music music: layakari practice riyaaz

by Warren

10 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Practice: Layakari And Melodic Variation Within A Bandish

When students remark that they “don’t know how to practice,” I usually interpret it as meaning that they haven’t yet internalized the processes of time allocation and work analysis to make the best use of their limited practice time — and they wind up doing vaguely “sloppy” practice and feeling guilty about not being more rigorous.

Now, don’t get me wrong. There is a time and a place for relaxed, sloppy practice. If all your practice is rigid and meticulous, you’re missing out on the serendipitous possibilities of musical free inquiry.

But instructions as to the methodology of messing around are a different order of being, and that’s not what this posting is about. Just as a singer should spend a certain amount of time in free play, he or she needs to put in some regular time on building the skills that will ensure easy, consistent and correct performance capability.

Probably the easiest of these skills to teach through a blog post is layakari, the manipulation of rhythm in interesting patterns — which is why previous practice postings have focused on this area. Today’s is no exception.

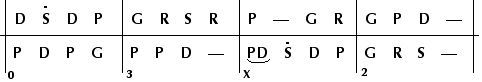

I will present another reductionist approach to developing layakari skills within the confines of a teentaal bandish.

Education Indian music music: layakari practice riyaaz

by Warren

1 comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Layakari Practice: The N+1 Game

Here’s another installment in my series of practice materials. This is another approach to the mastery of layakari in the 16-beat teentaal cycle. I call this the N+1 Game.

The object of this exercise is to explore a rich yet tightly constrained set of melodic materials in a variety of rhythmic phrasings. The same melody is sung in thirty-six slightly different rhythmic variations, each one fitting neatly into one cycle of teentaal.

Education Indian music music: layakari practice riyaaz tintal

by Warren

3 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

The Half-Speed Switcheroo: Rhythmic Cycle Practice in Exhaustive Detail

Let’s go back into the problems of working within rhythmic cycles (too many climate-change letters makes a dull blog, I know).

One of the most productive strategies for practicing rhythmic awareness is the half-speed switcheroo (note: I am not a nomenclatural traditionalist, so if you need paramparik lingo you’ll be disappointed). In this type of practice, a composed line is moved in and out of half-speed, first at the most important points of the taal (in tintal, that would of course be sam and khali), then at secondary, tertiary and quaternary points.

Let me demonstrate.

We’ll continue working with the simple sargam composition in Bhoopali:

The melody begins at khali, so the first shift into half speed will happen there, too. I’m just going to notate the transform using the first line; you can do the second line yourself (or make your students do it). Paper notation is useful but not really necessary; it’s a very good exercise to go through every aspect of this without writing anything down, keeping it all in your head, ears, voice and hands.

Education Indian music music: muscle training practice rhythmic cycles riyaaz tabla

by Warren

9 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Practicing Inside Rhythmic Cycles

One of the most challenging areas for many students of Hindustani music is working within rhythmic cycles. The ready availability of tabla machines has not solved this problem, because the core issue has more to do with not knowing how to practice than with not having a tabla player available all the time.

It is helpful to spend some time analyzing the various components of rhythmic-cycle practice. Once a singer begins this work, the cognitive load goes waaaaaay up; a lot more brain cells are required to keep all the elements of the musical equation under control. While holistic, gestalt-oriented practice is a must, it can be very helpful to break things down into smaller components and approach them with reductionistic ruthlessness.

To be competent in rhythmic-cycle-based improvisation, a singer must:

1 – be able to process rhythmic information concurrently with intonational information. That is to say, you have to be able to hear and feel the beats without getting distracted by them to the point that you go out of tune.

2 – be able to recognize important beats in the cycle and recalibrate according to position. That is, you have to hear crucial structural points and have enough cognitive strength available to lengthen or shorten your melodic line if necessary.

3 – be able to make coherent melodic shapes of specific lengths. In performance, it’s not enough to start an improvised melody at a specific point in the rhythm and finish it at another point — the melody you’re making needs to make sense. And (as if that weren’t enough) it needs to make sense at several levels; it has to be correct in raga terms, and it has to have gestural integrity. Those two are emphatically not the same thing.

Let’s take those distinct skills in turn, and I’ll discuss some ways of approaching them in the course of your practice.

Education music: music learning practice riyaaz

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Two Techniques for Regulating Your Practice

More from the Brian O’Neill Interview. This post has the two of us discussing two techniques for controlling the use of practice time to maximize ROI.

The Technique of a Hundred Beans

WS: Here is a very good technique that my teacher showed me for helping to regulate one’s practice: Get two bowls, or cups, and, from the supermarket buy a bag of kidney beans or garbanzo beans or something. Garbanzos are good for this. Count out a hundred of them. Put them in one bowl. Transfer one bean from the source bowl to the target bowl after each repetition of the line.

Later, I introduced a refinement. You see, you take one lick and you repeat it exactly a hundred times. My refinement was that sometimes in those bags of garbanzo beans you get one that’s misshapen or miscolored or something. I put that one in there, and whenever I got that one, I improvised for the same length of time. So at some point, I’d get a little vacation, and it was always a pleasant surprise.

BTO: What’s the unit of time per garbanzo bean?

WS: It was one lick, whatever the lick was — you know, typically not more than a minute. A hundred minutes is a long time!

BTO: Oh, each repetition?

WS: Yeah, each repetition. Finish a repetition, transfer a bean — This is the way to really regulate repetition.

If you don’t repeat it, then you wind up thinking that you know it, but not really having it there when you need it. It’s gotta be like tying your shoes, you know? It has to be completely fixed in muscle memory.

Index Cards

One way of handling the question of “what should I practice today?” is to get some index cards. On each card you jot down the nature of a particular practice, along with a stipulated length of time — however long that particular practice is going to last.

“Expanding & contracting, going up six notes and going down, and then doing that from the tonic, third and fifth of the natural minor scale.” 10 minutes

“Four-note paltas in Raga Kafi, from Mandra Pa to Tar Ma.” 20 minutes.

“Major 7, Dom 7, Minor 7 and Min7 b5 arpeggios in all twelve keys, through the cycle of fifths.” 25 minutes.

“Sightreading from Captain O’Neill’s book of fiddle tunes.”10 minutes.

“This specific piece of complex bol-bant in ‘Piyu pal na laagi mori ankhiyaa’ (Raga Gaud Sarang).”15 minutes.

“Fast scales in 16th note triplets across a two octave range, sung & played on guitar. 20 minutes. Starting at metronome thus-and-such, going up to at least metronome thus-and-such.”

And, so, every time that you invent a new practice, you note down what it is. Then, after a little while, you wind up with a batch of cards; you have, perhaps, 15 or 20 cards.

Then, after you’ve done your basic warm-ups, you shuffle the cards, and whatever comes up, you do that. And then your practice for the day is however many cards you can fit in the unit of time that you have allotted to practice. And then, here’s the nice part: the next day, you don’t just start where you left off — you shuffle the cards again.

Which means that some of the time you wind up doing the same practice three days in a row. But over all, over the space of, say, two weeks, you wind up meeting everything in there, and experiencing it as a sort of total repertoire of stuff to do. Then you may observe, in the course of those practices, “Huh, it really seems like in this part of this thing [= practice, card], I’m really not making it.” Then you design a lick that embodies that particular [problematic] thing, and that’s when you do the technique-building, metronome-incrementing practice (described in “One Lick for Two Hours.” Then you go back to that same practice [on the index card] next week or something, and you’ll ace it!

Education Indian music music: practice riyaaz

by Warren

4 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

More Notes on Practicing

More material taken from my long-ago interview with my student Brian O’Neill. This discusses a practice technique called:

One Lick for Two Hours

Now, when you’re trying to build up speed and technical fluency the following exercise is very useful:

Compose a line (preferably in your head) 2 or 3 notes at a time… and keep building it up until you have something that covers the range that you want to cover and includes whatever kind of technical things you want to address (scalar segments, intervallic jumps, whatever).

Switch the metronome on (at around 60 bpm) and do the line in half notes, keeping the metronome not on the downbeats, but on the upbeats (2 & 4). That is, your sung articulations and the metronome’s strokes aren’t happening at the same time.

Go through the whole line in sargam, in neutral syllables, and in open vowels. If you’re an instrumentalist, go through the line using individual articulations on each note, then with a legato approach.

At which point you double the speed, so that the same line is now sung in quarter-notes, one note per pulse. The metronome needs to stay on the offbeats! Again, do it in sargam, neutral syllables and one or two open vowels.

Then go back to the original tempo and revisit that for a few iterations.

Now move the metronome up a click. If you have a digital metronome, go up by three or four beats per minute.

Repeat the process exactly as before, and when you’re done, move the metronome up another few bpm.

Eventually you’ll get up to mm 120, which is exactly double your starting tempo. Do the same exercise at that tempo…and then shift the metronome back to 60.

Only this time, maintain the same sung/played speed you had at mm 120 — with the metronome at the slower tempo. Now you’ll be singing the line in quarter and eighth notes relative to the speed of the metronome.

Repeat the alternation of “single” and “double” speed, with the metronome still on 2 and 4. (For extra credit, why does this practice work better when the metronome’s on the offbeats?). Keep going up by a few bpm at a time.

Eventually you’ll reach a point where you can go no further; a point where your technique is on the edge of failure.

Don’t stop the practice just yet. Instead, back down by a notch or two, repeat the material, then back down again. Do this eight or nine times, so that when you finally conclude the practice, you’re midway between your maximum speed and mm 60.

Stop.

Go take a walk or something. That’s enough of that practice for the day.

This is not a ten minute practice, this is a two hour practice. Two hours on one lick. The important thing is to keep that process going, all the way up and then retreat, incrementally, back down to about halfway from your original starting point.

This gradual up and down incrementation turns out to be very useful for building a solid technique at all levels of speed. It’s boring as hell, but it works a treat.

I remember sitting down to practice in my apartment in Pune. I was practicing Yaman, I sat down to practice, and I practiced one line for about an hour and forty-five minutes — using this metronome technique. Then I finished, I turned off the sruti box, and immediately my doorbell rang. And I went over and it was Atul, the sitarist in my ensemble. And he said, “That was incredible!” I said, “You were listening to the practice? How long were you there?” He said, laughing, “Oh, I arrived just before you began!” So he had been outside my door for an hour and forty five minutes listening to me go over the same thing and he was completely thrilled to have heard this practice. That was very interesting to me. Not everybody would find that interesting, but Atul did.

Education Indian music music: paltas patterns permutations practice Raga riyaaz

by Warren

9 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Thinking About Palta Exercises

More of the material from my long-ago interview with my student Brian O’Neill. Here, I discuss the permutational practice routines known as Palta Exercises.

Hindustani musicians already know what I’m talking about. Western musicians will describe them as short phrases transposed up and down a scale: 123, 234, 345, 456, etc.

Paltas can be practiced within ragas, of course, but they are also useful for practicing ear-training and pattern manipulation inside scales.

To clarify the distinction: a palta in Raga Bhimpalasi would accommodate the omission of the second and sixth degrees in ascent, and the inclusion of these notes on the way down. Violating the raga’s rules of motion is off the table. On the other hand, a palta in Kafi Thaat (the Dorian mode, if you will) would not have any such restrictions.

Here’s a useful way to do paltas:

Pick a scale — any scale, preferably one that has 7 notes. Take a single short pattern (let’s call it a “cell”), and transpose it up and down in the scale.

For example:

S N S / R S R / G R G / M G M / P M P / D P D / N D N / S N S

N D N / D P D / P M P / M G M / G R G / R S R / S N SAnd once you’ve memorized it, then do another pattern.

S N D / R S N / G R S / M G R / P M G / D P M / N D P / S N D

S R G / N S R / D N S / P D N / M P D / G M P / R G M / S R G…Again, do that for 10 minutes.

And then alternate the two patterns, one after the other. Do it all from memory.

Then combine the two patterns:

S N S / S N D

R S R / R S N

G R G / G R S

M G M /M G R

P M P / P M G

etc., over as much of a range as you feel comfortable singing or playing.Then try combining the two in the other order:

S N D / S N S

R S N / R S R

G R S / G R G

M G R / M G M

P M G / P M P

etc.Try doing two iterations of the first “cell” and one of the second:

S N S / S N S / S N D

R S R / R S R / R S N

G R G / G R G / G R S

etc.Begin making up your own combinations of cell sequences, always using your memory to keep the material fresh in your mind’s ear.

Try, instead of alternating cells, alternating successive notes of the two different cells. S N S / S N D thus becomes S S N N S D; S N D / S N S becomes S S N N D S.

Instrumentalists should be singing these patterns as well as playing them. It is also a very good exercise to sing while fingering them on your instrument (without activating it in any other way). This builds a powerful cognitive link between instrument and voice that pays off in future fluency and expressiveness.

Education Indian music: hindustani music practice rhythmic cycles riyaaz tala theka

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Understanding Tala – Internalizing Talas and Thekas

A thread on rec.music.indian.classical (USENET) attracted my attention today.

It started with a request:

“I am learning ICM at my own and also attending community school once in a week. I have following question when I tried to practice at home.”

1) In Teen Taal (16 Beats) From which beat the composition/bandish/alaap etc. starts ? i.e. should I start from Taali or Khali which beat #. ( I am using Radel DigiTaalmala)

2)Is there any book available to teach me the basic concept of starting composition with any Taala ? (means which will show me that in “xyz” taal – the composition will start from taali or khali or 3

or 4th beat etc.)Your advice/response will be highly appreciated.

With Kind Regards

Chandrakant

I responded as follows, in what strikes me as a pretty good summary of the advice I am frequently giving my students about working with theka:

There are two different issues at play here.

One is to understand the internal structure of the tala.

To do this it is very useful for a vocalist to practice theka

recitation. Note the relationships of the tabla bols to the tongue

and laryngeal position.All important right hand strokes use unvoiced dental “t” sounds: ta,

tin, tun tet. Na is the anusvar of that tongue position. Recite “ta

tin tin ta” over and over; experience the difference in overtone

structure between the “a” vowel and the “in” phoneme as each is

triggered by the “t” tongue attack.All important left hand strokes use the velar consonants. Ge and

Kat. Ge is a voiced velar that is sustained on an “e” vowel, Kat

begins with an unvoiced velar and ends with a retroflex “T” stop.Recite “Ge Ge Ge Ge Kat Kat Kat Kat” over and over, experiencing the difference between the voiced sustained and the unvoiced stopped velars.

But what of strokes that use both hands? Discover for yourself that

it is impossible to say “Ta” and “Ge” simultaneously. Try it; your

tongue won’t be able to do it.So how to speak the syllables for these strokes? Simple. Change the unvoiced dentals of the right hand to voiced dentals: ta + ge = dha; tin + ge = dhin, etc. Recite “Dha Dhin Dhin Dha” and feel that there is sonic activity taking place in two places in your vocal mechanism. Your vocal chords are making a steady stream of impulses (basically “uh uh uh uh uh uh” since shaping vowels is done by the mouth), and your tongue is articulating lightly between your teeth (“ta tin tin ta” etc.). The front of your mouth is the high drum, your throat is

the low drum.Now recite theka for a long time, and experience the rise and fall of impulses in your throat and mouth as you move through the cycle. Pay particular attention to the return of your vocal chords on the 14th matra, emphasize “dhin dhin Dha DHA” — that’s the sam.

In order to understand the relationship between the bandish and the theka, it is very useful to recite theka while listening to vocal recordings. In this you want to have standard professional accompanists; attempting to recite theka while Zakir is embellishing is much more difficult. On many older recordings, tabla is very low in the mix. I often tell my students to listen to someone like Veena Sahasrabuddhe as her recordings are generally mixed very well and the tabla players are people like Omkar Gulwady, who keep beautifully flowing theka without much finger-chatter.

Listen to many different bandishes while you recite. Observe the many different ways they have of coming to the sam and maintaining a relationship with it.

A useful exercise is (once you know where the sam is located on a

particular bandish) to sing one line of the chiz, then recite theka

*from the point in the cycle where the song begins*. Thus, an 8-beat mukhda would start on khali; one would sing the song text once, then recite, starting at khali: “Jabse tumhi sanga LAagali / Dha tin tin ta ta dhin dhin dha DHA dhin dhin dha dha dhin dhin dha / Jabse tumhi sanga laagali / Dha tin tin ta ta dhin dhin dha DHA, etc., etc.” A five-beat mukhda, on the other hand, might yield something like “Bolana LAAgi koyaliyaa / ta ta dhin dhin dha DHA dhin dhin dha dha dhin dhin dha dha tin tin / bolana LAAgi koyaliya / ta ta dhin dhin dha DHA, etc., etc.”Practice these approaches assiduously and enthusiastically and you will gain many interesting rhythmic insights.

Warren

Education Indian music music: intonation khyal learning practice riyaaz singing

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Practice Tips and Techniques, No. 1

About ten years ago my student Brian O’Neill and I had a long discussion about practice techniques. He transcribed it and sent it along to me, and it languished on my hard drive. Recently, I remembered the material and dug it out. It needs editing, so it’s going to take a while to get it all tidy, but there’s some worthwhile stuff in that document. The first part of the conversation was about practicing the drone — the most basic type of self-tuning a singer can do.

WS: When I started out I did not have any particular deep sense of discipline in practice. Eventually I began by starting every day with a drone session. I would just sing the tonic, the Sa. And I would focus on that, and I would…

BTO: Tune up?

WS: Yeah. You try & get your temporomandibular joint a little bit loose; you do a little bit of overtoning; some tongue stretches; try and make sure the soft palate is down and you’re getting sinus resonance. What I tell my students is to begin with a little session (it might be 10 minutes) of Sa, every morning. And when you do that, you examine different variations.

For example, subtle intonational shifts. Get on Sa and move the note the smallest possible amount flat, then return it to the center, then move it sharp and return it. What you’re really doing is, you’re decreasing the intonational standard deviation of the pitch.

So that’s one approach to the Sa.

Another approach is breath control. You get a watch with a sweep second hand, sing Sa [one breath’s worth], and time yourself. “Hmmm, that was 11 seconds. OK, I’m going to go for 12.” And then you ask yourself, “Where does most of the air go out? Oh, most of the air goes out in the very first half a second. OK, let me try and regulate that. Good!, I got 5 more seconds on that.” So those are all good ways of occupying yourself on the drone. So 10 minutes turns out to be nowhere near enough time, and you just pick one or another of those exercises to do with the tonic.

There’s a lot more to come, including very specific methods for organizing your practice to get the most effective study in the time you have available. Stay tuned!

Finally, a word on a related subject.

If you’re studying or teaching music, you’re engaged in the long, slow, work of taking parts of our past and preparing them to travel into the future.

Therefore, you owe it to yourself and to the music you cherish — to educate yourself about climate change.

No stable climate – no music. It’s as simple as that.

MUSIC IS A CLIMATE ISSUE