Education Indian music music: layakari practice riyaaz

by Warren

10 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Practice: Layakari And Melodic Variation Within A Bandish

When students remark that they “don’t know how to practice,” I usually interpret it as meaning that they haven’t yet internalized the processes of time allocation and work analysis to make the best use of their limited practice time — and they wind up doing vaguely “sloppy” practice and feeling guilty about not being more rigorous.

Now, don’t get me wrong. There is a time and a place for relaxed, sloppy practice. If all your practice is rigid and meticulous, you’re missing out on the serendipitous possibilities of musical free inquiry.

But instructions as to the methodology of messing around are a different order of being, and that’s not what this posting is about. Just as a singer should spend a certain amount of time in free play, he or she needs to put in some regular time on building the skills that will ensure easy, consistent and correct performance capability.

Probably the easiest of these skills to teach through a blog post is layakari, the manipulation of rhythm in interesting patterns — which is why previous practice postings have focused on this area. Today’s is no exception.

I will present another reductionist approach to developing layakari skills within the confines of a teentaal bandish.

In this article I’m using the first line (mukhda) of the famous Malkauns composition mukh mora mora musakaata jaata (“laughingly turning her face, she goes”) as an example, but it’s a good idea to go methodically through these exercises in whatever bandish you happen to be practicing at the moment.

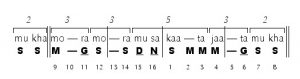

Here’s the first line of mukh mora mora in Romanized Bhatkhande notation:

First, count the words.

Mukh / mora / mora / musakaata / jaata

There are five words; W = 5. The total number of permutations in this exercise is W squared: 25.

How many beats in each word?

mukh = 2

mora (1) = 3

mora (2) = 3

musakaata = 5

jaata = 32 + 3 + 3 + 5 + 3 = 16

There are two parts of this exercise. First, using text syllables and melodic variations. Second, reciting tabla bols for the appropriate parts of the theka, going through all the permutations in exactly the same way.

FIRST — TEXT & MELODY:

Each word in the song segment gets a new melody line, built up one word at a time from the starting word, and keeping the original word length unchanged.

Let’s say I begin at mukh, which is two beats long in the original. That means I need two beats’ worth of melody — and for ease of singing, it should be melody that links easily with the starting note of the next word in the sequence, which will be sung as it usually is.

The second pass through the material asks for new melody on the first and second words. The next word is mora (1), which lasts three beats in the original — so I must add three more beats’ worth of melody that connects nicely to the original melody at mora (2). The third pass through the material asks for new melody on words 1, 2 and 3 — from “mukha” to “mora (2).” See how this works?

1st word to:

2nd word: beat 7 to beat 8

(starts at “mukha,” rejoins “mora (1)”) = 2;

3rd word: beat 7 to beat 11

(starts at “mukha,” rejoins “mora (2)”) = 5;

4th word: beat 7 to beat 14

(starts at “mukha,” rejoins “musakaata”) = 8;

5th word: beat 7 to beat 3

(starts at “mukha,” rejoins “jaata”) = 13;

1st word: beat 7 to beat 6

(starts at “mukha,” rejoins “mukha“) = 16;

I composed some melodic variations, just to give the basic idea — but please compose your own; there is nothing particularly special about the lines I’ve written.

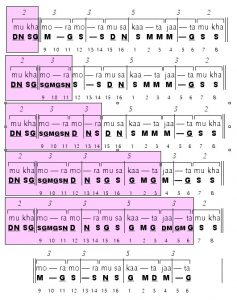

Here is the complete set, beginning on “mukha.” Each successive variation is one word longer; the final 16-beat variation rejoins the original melody at the starting word. For your convenience, the variations are highlighted.

Next, let’s start the variations on the second word of the song, in this case “mora (1).”

2nd word to:

3rd word: beat 9 to beat 11

(starts at “mora (1),” rejoins “mora (2)”) = 3;

4th word: beat 9 to beat 14

(starts at “mora (1),” rejoins “musakaata”) = 6;

5th word: beat 9 to beat 3

(starts at “mora (1),” rejoins “jaata”) = 11;

1st word: beat 9 to beat 6

(starts at “mora (1),” rejoins “mukha”) = 14;

2nd word: beat 9 to beat 8

(starts at “mora (1),” rejoins that word) = 16;

3rd word to:

4th word: beat 12 to beat 14

(starts at “mora (2),” rejoins “musakaata”) = 5;

5th word: beat 12 to beat 3

(starts at “mora (2),” rejoins “jaata”) = 8;

1st word: beat 12 to beat 6

(starts at “mora (2),” rejoins “mukha”) = 11;

2nd word: beat 12 to beat 8

(starts at “mora (2),” rejoins “mora (1)”) = 13;

3rd word: beat 12 to beat 11

(starts at “mora (2),” rejoins that word) = 16;

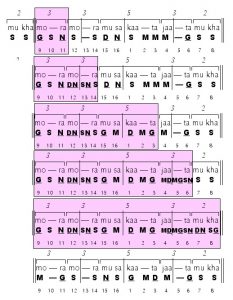

4th word to:

5th word: beat 15 to beat 3

(starts at “musakaata,” rejoins “jaata”) = 5;

1st word: beat 15 to beat 6

(starts at “musakaata,” rejoins “mukha”) = 8;

2nd word: beat 15 to beat 8

(starts at “musakaata,” rejoins “mora (1)”) = 10;

3rd word: beat 15 to beat 11

(starts at “musakaata,” rejoins “mora (2)”) = 13;

4th word: beat 15 to beat 14

(starts at “musakaata,” rejoins that word) = 16;

5th word to:

1st word: beat 4 to beat 6

(starts at “jaata,” rejoins “mukha”) = 3;

2nd word: beat 4 to beat 8

(starts at “jaata,” rejoins “mora (1)”) = 5;

3rd word: beat 4 to beat 11

(starts at “jaata,” rejoins “mora (2)”) = 8;

4th word: beat 4 to beat 14

(starts at “jaata,”rejoins “musakaata”) = 11;

5th word: beat 4 to beat 3

(starts at “jaata,” rejoins that word) = 16;

Remember, the composed variations I’ve supplied are just filler. You (or your students) should compose your own. I usually go through each line multiple times, trying to create variations that start on all convenient scale-tones.

Try this process out on the bandishes you’re practicing. Count the words in the first line, and begin developing elaborations in the same way. It’s fun, and it will keep you engaged with the material much longer than you would have been otherwise.

SECOND – USING TABLA SYLLABLES:

This is really simple.

Do exactly what you’ve just done, only this time, instead of making up a melodic variation, simply recite the tabla bols that match whatever part of teentaal you’re in.

Thus:

Dhin-Dha-mora mora musakaata jaata

Dhin-Dha-Dha-Tin-Tin mora musakaata jaata

Dhin-Dha-Dha-Tin-Tin-Ta-Ta-Dhin musakaata jaata

Etcetera, etcetera.

Do all twenty-five of these (or whatever number is appropriate for the bandish you’re working on).

This exercise will solidify your relationship to the theka more than anything else I can suggest. Do it while keeping taal; don’t use a tabla machine until you’ve gotten it solidly internalized in muscle memory.

Finally, a word on a related subject.

If you’re studying or teaching music, you’re engaged in the long, slow, work of taking parts of our past and preparing them to travel into the future.

Therefore, you owe it to yourself and to the music you cherish — to educate yourself about climate change.

No stable climate – no music. It’s as simple as that.

MUSIC IS A CLIMATE ISSUE</strong

>

Warren, You are a amazing teacher,thanks for sharing you knowledge.Can’t thank you enough.

it’s crystalline, the way the form repeats upon itself. and beautiful even to Look at in your finely illuminated manuscript. Yes, i, too would like to hear the examples on audio. Thank you.

Excellent explanation! Only you can do this.

would you be able to post the audio clip of these exercises under them?

Good, very intelligent exercise…

Awesome explanation of layakari. Thanks, Warren.

Wonderful!

This should keep me busy and organised for a while. Thanks for the post.

Pretty glorious stuff, Warren. You go, guy.

Thank you for the post, this is a wonderful lesson!