India Indian music music Personal vocalists Warren's music: concert khyal Raga

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Toronto Concert, July 20, 2013

Toronto, June 20, 2013. Ragas Kamod, Nayaki Kanada, Pahadi, Bhairavi. With Ravi Naimpally on tabla and Raya Bidaye on harmonium, performing under the auspices of Toronto’s Raga Mala society.

Music videos below the fold:

India Indian music music Personal Warren's music: concert mehfil Raga

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Pune Concert, August 11, 2013

A mehfil at a private residence in Pune, with Chaitanya Kunte on harmonium and Milind Pote on tabla. A dream team of accompanists, and made more special by the presence in the audience of Rajeev, Medha, and Eeshan Devasthali. A lovely evening.

Here are ragas Chhayanat, Bihagada, Jayant Kanada, Khamaj, Gorakh Kalyan and Bhairavi. There are some other short items which I haven’t posted yet.

Music videos below the fold:

Education India Indian music music Personal: autodidacticism heuristics learning lecture-demonstrations

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Composers & Improvisors: Invent Your Own Raga!

This is a rough approximation of the content of my lecture-demonstration on raga. This is how I introduce students in a university classroom to the underlying conceptual structure of raga-based melody:

With a simple recipe for making our own raga.

Here’s what we do:

Start with a tonic – fifth drone. Choose a second degree – either natural or flat. Choose a third degree – either natural or flat. Choose a fourth degree – either natural or sharp. Choose sixth and seventh degrees – either natural or flat.

For example, let’s say we choose: 1, b2, 3, #4, 5, 6, b7, 8.

Play or sing this for a few minutes over the drone to experience the intervals.

Now, pick a number between 2 – 4. For example, 4.

Pick a number between 5 – 7. For example, 7.

Now we play/sing the original scale, but this time OMIT 4 & 7 on the way up, and include them on the way down. Thus:

1, b2, 3, 5, 6, 8 — 8, b7, 6, 5, #4, 3, b2, 1.

We play or sing this for a few minutes over the drone so we can learn the interval structure…the diminished triad ascending from the 2, the juicy diminished fourth that emerges on the way down between the b7 and the #4…all kinds of goodies are there to be found. Notice that certain phrases evoke ascent and others descent, giving improvisation a lot of motion.

Just going this far generate a ton of beautiful material. But there is one more refinement we can make on the process which will make our “raga” hang together even better.

Pick a group of three adjacent numbers. Any three; doesn’t matter. Let’s say we pick 5,6,7. Now…take those three notes, and make up a special tweak — just a little phrase, or a small shift in the sequence. For example, we’ll make the descent from the upper octave ALWAYS follow the rule 8, 6, b7, 5 — expressly forbidding a straight pathway.

Mess around with this for a while and we’ll start generating melodies automatically.

There is nothing special about this particular combination of intervals.

There are many ragas in the Hindustani system which are entirely built from an ordinary major scale.

In general, inside any raga, the more complex the intervals, the harder it is to *hear*; the more complex the rules of ascent/descent/tweaking, the harder it is to *think*.

Mess around. See what you can come up with.

Education environment music: climate change cultural extinction extinction music

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Music Is A Climate Issue — Endangered Musics: Sunda

I am not a climate scientist. I’m a scientifically literate musician. Climate change scares me for dozens of reasons. And it makes me deeply and terribly sad.

With rising sea levels, many island nations will lose much of their land, or even cease to exist. Which raises the question:

What music will become extinct?

A look at the list of island nations gives you a sense of what’s at stake. A large nation, like Indonesia, will experience incredible economic impacts and the forced inland migrations of entire regional populations. Perhaps millions of people will be forced by rising sea levels to abandon their homes and their traditions. A small island nation may find its land area reduced to the point of unsustainability; its culture and population forced into refugee status.

Languages will become diluted and eventually dissipate. Cultural forms (like dance, drama, traditional storytelling, and music) will lose much of their context and setting, eventually becoming preserved by a few interested afficionadi as “museum pieces” — no longer embodied as living, breathing traditions.

There are a lot of island nations. Each one has its own music.

For example, in Indonesia, there is an ethnic group called the Sunda:

The Sundanese are of Austronesian origins who are thought to have originated in Taiwan, migrated though the Philippines, and reached Java between 1,500BCE and 1,000BCE.[2]

According to the Sundanese legend of Sangkuriang, which tells the creation of Mount Tangkuban Parahu and ancient Lake Bandung, the Sundanese have been living in the Parahyangan region of Java for at least 50,000 years.[citation needed]

Inland Sunda is mountainous and hilly, and until the 19th century, was thickly forested and sparsely populated. The Sundanese traditionally live in small and isolated hamlets, rendering control by indigenous courts difficult. The Sundanese, in contrast to the Javanese, traditionally engage in dry-field farming. These factors resulted in the Sundanese having a less rigid social hierarchy and more independent social manners.[1] In the 19th century, Dutch colonial exploitation opened much of the interior for coffee, tea, and quinine production, and the highland society took on a frontier aspect, further strengthening the individualistic Sundanese mindset.[1]

Court cultures flourished in ancient times, for example, the Sunda Kingdom, however, the Sundanese appear not to have had the resources to construct large religious monuments similar to those in Central and East Java.[1]

Wikipedia says around 27 million people speak Sunda. That’s a lot of people.

Here’s some of their music. It’s beautiful.

This music is called Kacapi Suling, a style which developed in the 1970s. The name simply refers to the instruments involved. There are two stringed instruments (kacapi) and a flute (suling):

The Sundanese zither (kacapi) often serves to represent Sundanese culture. It plays as either a solo or an ensemble instrument, associated with both villagers and aristocrats. The instrument may take the form of a boat in tembang Sunda, or the form of a board zither in kacapian.

{snip}

In a typical performance (still primarily in recordings, as kacapi-suling is rarely performed live), the kacapi player outlines a cyclic structure of a song and the suling player improvises a melody based on the original song from the tembang Sunda repertoire. Kacapian refers to a flashy style of playing a board zither, and it is known as one of the sources of Sundanese popular music. It can be accompanied by a wide variety of instruments, and can be played instrumentally or as the accompaniment to either a male or female vocalist.

What will rising sea levels, an acidified ocean, and drastically increased heat do to Sunda, and to the rest of Indonesia?

Climate Change in Indonesia:

The devastating impact of global warming is already evident in Indonesia and will likely worsen due to further human-induced climate change, warns WWF.

The review from the global conservation organization, Climate Change in Indonesia – Implications for Humans and Nature, highlights that annual rainfall in the world’s fourth most populous nation is already down by 2 to 3 per cent, and the seasons are changing.

The combination of high population density and high levels of biodiversity, together with a staggering 80,000 kilometres of coastline and 17,500 islands, makes Indonesia one of the most vulnerable countries to the impacts of climate change.

Shifting weather patterns have made it increasingly difficult for Indonesian farmers to decide when to plant their crops, and erratic droughts and rainfall has led to crop failures. A recent study by a local research institute said that Indonesia had lost 300,000 tonnes of crop production every year between 1992-2000, three times the annual loss in the previous decade.

Climate change in Indonesia means millions of fishermen are also facing harsher weather conditions, while dwindling fish stocks affect their income. Indonesia’s 40 million poor, including farmers and fishermen, will be the worst affected due to threats including rising sea levels, prolonged droughts and tropical cyclones, the report said.

“As rainfall decreases during critical times of the year this translates into higher drought risk, consequently a decrease in crop yields, economic instability and drastically more undernourished people,” says Fitrian Ardiansyah, Director of WWF-Indonesia’s Climate and Energy Programme. “This will undo Indonesia’s progress against poverty and food insecurity.”

WWF’s review shows that increased rainfall during already wet times of the year may lead to high flood risk, such as the Jakarta flood of February this year that killed more than 65 people and displaced nearly half a million people, with economic losses of US$450 million.

Climate change impacts are noticeable throughout the Asia-Pacific region. More frequent and severe heat waves, floods, extreme weather events and prolonged droughts will continue to lead to increased injury, illness and death. Continued warming temperatures will also increase the number of malaria and dengue fever cases and lead to an increase in other infectious diseases as a result of poor nutrition due to food production disruption.

Sunda Islands Part of the coral triangle, one of the most diverse coastal areas. Already at threat from destructive fishing and reef fish trade.

Education environment music Personal: agriculture culture ethnomusicology sustainability

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Year 4, Month 8, Day 12: Oh, Didn’t We Ramble?

The NOLA Defender (New Orleans, LA) gives the Big Easy’s perspective on climate:

Global warming often conjures images of melting ice caps and smokestacks spewing soot. On Friday, a group of New Orleans cultural pillars put brass bands and New Orleans food in the conversation. Community leaders and climate change awareness activists flooded the docks at Mardis Gras World Friday afternoon to support the I Will #ActOnClimate campaign, and to discuss the potential impact of climate change on New Orleans.

After Glen Hall III, of the Baby Boys Brass Band, piped out his rendition of the National Anthem on the trumpet, New Orleans Tourism Marketing Corporation President and CEO Mark Romig gave his opening comments.

“We are all affected by climate change, including this city’s tourism industry, which is a major economic driver,” he said. “Tourism relies on the things that make New Orleans so great, like our picturesque wetlands, our world-renowned seafood, our rich culture, our heritage, all of which are at risk due to the changing climate. Chefs, musicians, tour guides, artists, and event planners have gathered here to urge action to end climate change. Not only for the sake of our industry, but because we have a moral obligation to future generations.”

This one was pretty deeply felt. July 21:

Blues and jazz may have been born of hard times, but New Orleans’ musical genius took its character not only from sorrow and oppression, but from the region’s productive agriculture and essentially benign environment. The same is true everywhere in the world: music flourishes where there’s enough to eat, where people have enough security to devote time to refining their artistry, and performing for audiences, and teaching their craft to others. Thanks to its location, the Crescent City is feeling the punishing effects of climate change more immediately than many other locations, so this formulation is no abstraction.

Whether it’s New York or New Delhi, Laos or Louisiana, the arts only flourish when the climate allows people to invest their time in cultural expression. Subtract climatic stability, and it’s not just agriculture and infrastructure that’ll suffer; without a habitable future, all of humanity’s priceless and unique musical expression is at risk.

Warren Senders

Education India Indian music music Personal vocalists

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

An Excellent Sort Of Memory: Creativity in Khyal Singing

This essay was written for the recent Learnquest Conference and printed in their program guide.

============================================================

“The past does not influence me. I influence it.”

— John Cage —

“It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards.”

—The White Queen, to Alice —

Hindustani music is rich in paradoxes of aesthetics, pedagogy, personality, imagination and execution — paradoxes which, ceaselessly spinning, provide a source of creative power within this complex and interdependent universe.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the endless push and pull between imagination and tradition. A khyal performer is expected to show the imprint of her or his teachers, and therefore the imprint of their teachers as well. A performance is unsatisfying to the educated listener if it is entirely of the moment; rather, the imprimatur of multiple artistic and pedagogical generations is what lends depth and resonance to a singer’s music. To the educated ear, a singer’s influences lend themselves to as many interesting combinatorial possibilities as the notes of a complex raga.

For example, Vamanrao Deshpande (in “Indian Musical Traditions”) recounts the khyaliya Miya Alibaksha’s response to the singing of Bhaskarbuwa Bakhle:

“…in response to a request from Alibaksha Saheb, Buwa took up the vilambit khayal ‘Tu aiso hai Karim’ from raga Darbari which was followed by the fast khayal ‘Nain so nain.’ The recital was punctuated with appreciative comments from Miya Alibaksha: ‘This is the gamaktan of Haddu Khan Saheb; this is reminiscent of Faiz Mahammad Khan’s elaborative skill; this is Rahimat Khan’s phirat (rapid ‘wandering’ passages); this intricate tana reminds me of Mubarak Ali….Bhaskarbuwa’s music is excellently developed in all respects.”

Indeed.

And Mohan Nadkarni describes Bhimsen Joshi’s interweaving of source material in his biography of the great vocalist:

“It is in his drut singing that Bhimsen presents a rare amalgam of gayakis as diverse as those of Gwalior, Atrauli-Jaipur, and Patiala. For example, right in the midst of a Patiala-style sapat taan, he can startle his listeners with a lightning array of intricate, odd-shaped patterns from the Atrauli-Jaipur gharana. A sarangi-like, seemingly slippery flourish from the Kirana style would then be deftly grafted to the laya-oriented taankari of the Gwalior tradition. Who else, but a maestro of his talent and genius, can achieve such marvelous homogeneity in content, treatment and approach?”

While this would suggest that a singer is collagistically assembling a performance from a collection of vocal mannerisms, techniques, and methods, the model of khyaliya-as-bricoleur is incomplete. Singers who’ve received training from multiple teachers do not automatically become creative aggregators; they are in fact more likely to display a kind of musical multiple-personality syndrome in which different pieces are rendered in the styles of their originators. I vividly remember a Pune concert in the mid-1980s in which a young vocalist (who has since gone on to recognition and acclaim) rendered successive pieces in the styles of three separate major vocalists. The first piece was a Marwa uncannily sung in the style of Amir Khan, the second a Darbari Kanada presented a la Bade Ghulam Ali, followed by an equally derivative thumri. While the tonal material of the ragas was skillfully handled, the artist’s music was hardly “excellently developed in all respects.”

Musicians sometimes choose security over danger, exalting their own preceptors and lineage at the expense of their own individuality. There are two ways this manifests. The first is an over-reliance on traditionally sanctified methodology; those who play it safe in this way are criticized with words like “dry” and “grammatical.” The second is epigonisation, in which the Master is imitated so thoroughly and completely that all vestige of the human artist is submerged under the borrowed mannerisms and repertoire of a single more charismatic and culturally dominant figure. A prominent disciple of a very popular khyal singer was known within the musicians’ community as “HMV” — His Master’s Voice — for his slavish duplication of his guru’s mode of singing.

The road to genuinely innovative musicianship in the khyal idiom, then, is as cluttered and obstructed as any Indian street. A singer can be too timid, too dominated by a single guru or charismatic figure, too susceptible to the influences of the moment or those of the century.

While the central paradox (a constantly changing improvisational genre operating freely within the constraints of centuries of tradition) is unresolvable, a study of the ingredients of musical expression offers some insight.

In any khyal performance we witness the superimposition of multiple sets of constraints and stipulations within which the singer is charged with finding himself or herself.

Most obvious to the listener is the raga itself. Ragas provide the tonal material for extensive improvisations and elaborations; taught orally, they can be described structurally using widely understood formulae (N notes in ascent, N+x notes in descent, this note emphasized, that note de-emphasized, this melodic phrase heard cadentially, that melodic phrase heard rarely, this part to be treated strictly, that part to be treated freely, the whole adding up to a recipe for sustained variation). A singer must present this material accurately, avoiding not just errors of intonation or omission but also unintended passages from other ragas with similar structures. Certain ragas are common property; others are so inextricably associated with particular artists or lineages that performing them is fraught with pitfalls for anyone outside the proprietary circle. The challenge for the khyaliya is to render the raga with structural fidelity while finding something new — a melodic road less traveled by. A singer who offers only the standard formulae may find praise for his or her fidelity to the tradition — but is equally likely to be dismissed for lack of useful insight.

The fact is that even in the most tightly constrained raga structure, there are always new combinations, phrases and gestures awaiting discovery. A singer who abdicates this responsibility fails the central task of khyal.

The raga repertoire subsumes the bandish repertoire; certain songs are likewise known and performed by, almost all professional singers, while others are a single singer’s “personal private thing.” Ragas are sometimes announced by their affiliations. It is common to speak of an “Agra bandish,” or a “typical Jaipuri chiz,” and educated listeners will recognize these pieces like old friends, acknowledging their association with particular styles and the expectations this raises for the specific content of a performance.

There are some compositions (e.g., “Sakhi mori rum jhum” in Durga, “Jabse tumhi sanga” in Bhoopali) which were fixtures in the professional repertoire of the early twentieth century, but have now become propadeutic vehicles on which aspiring singers can cut their teeth. The American baseball great Yogi Berra once commented of a particular restaurant that, “Nobody goes there anymore because it’s too crowded.” It could be said of these songs that, “Nobody sings them anymore because they’re too popular.”

Conversely, a “rare” bandish may be announced with considerable fanfare. Some of these items are in fact newly composed — but Hindustani musical culture devalues the new and exalts the old. More prestige accrues to an ancient or unusual song than to a new item, so it’s not uncommon for performers to give their own compositions a provenance far back in the tradition, sometimes including the pen-name of a noted historical composer in the song text, lending the piece further credibility. While it’s tempting to regard this reverse plagiarism as an ethical transgression, it can also be seen as an organic manifestation of the tradition’s fluidity and creativity: four hundred years after his death, Sadarang (the pen-name of Niyamat Khan, a great khyal composer) continues to create new material!

The particular structure of the bandish may have a huge influence on the performance as a whole. This is especially true of medium and fast tempo songs, whose rhythmic structures and melodic contours direct improvisation in particular ways. For example, a song with high syllabic density nicely supports text-based rhythmic variations (known as “bol-bant”), while one with fewer syllables and more prominent melismata is a felicitous vehicle for virtuoso melodic passagework.

Intersecting with these fields of constraint is the responsibility a singer bears to her or his musical extended family. The guru, the guru’s guru, the guru’s guru’s guru, the guru’s brother’s guru, the guru’s brother’s guru’s brother’s disciple, etc., etc. — all contribute to an environment in which some musical behaviors are privileged above others, leading eventually to culturally accepted formulations in which particular lineages (known as “gharanas”) are recognized for expertise in particular aspects of khyal.

Musically adept listeners can recognize a singer’s gharana very easily — and conversely, if a singer’s gharana is known and announced, a trained listener will already have a good idea of what the performance will be like. In performance, khyaliyas are expected to develop a coherent portrait of their lineage — while they’re also developing the raga material and exploring the contours of the song. Singers may be criticized for violating the aesthetic guidelines of their gharanas, or for being overly conservative in their expression of those same guidelines — a dilemma which parallels the critique on raga-interpretation grounds. From one perspective, the gharana provides the conceptual framework for a raga’s expression; from another, the raga is the medium through which a gharana’s characteristics are expressed.

The guru himself or herself is the principle source of a khyaliya’s repertoire of songs and conceptual resources, and respect for the guru is foundational in Hindustani pedagogical tradition. Singers frequently attribute their own successes in performance to their gurus’ virtue and genius. In much the same way that the bandish is a single crystallized expression of a raga’s characteristics, the guru can be understood as a single human expression of a gharana’s salient features — and in the same way that singers strive to express the raga’s essential qualities, they wish to express some of their guru’s musical conceptions as well. The guru’s experience, values, aesthetics, vocal production, kinesics, and a host of other elements are, for better or worse, transmitted to the disciple.

And, finally, there is the individual singer herself or himself. Singers strive to integrate the influences of repertoire, gharana, and guru in the moment of performance and in the process of teaching their own disciples; while the precise relationship is always fluid and varies from artist to artist — and indeed from moment to moment — the general tendency is an avoidance of extremes — what can be described as a “conservation of innovation.” An unusual repertoire item (a rarely heard or newly composed raga or bandish) will usually receive a palpably traditional mode of presentation, while a predictable repertoire choice may need to be counterweighted by a more novel treatment if it is to engage listeners. The most notable exception to this principle would be Kumar Gandharva, who presented newly composed ragas in a highly original style, triggering tradition-versus-innovation controversies that continue to this day.

To describe a khyaliya as “creative,” then, is to recognize the success of a balancing act in which freshly imagined melodies and rhythms are endlessly re-contextualized in a historically-grounded milieu. The listeners’ understanding of a singer’s musical heritage undergoes continual revision in the light of each new passage, each new improvisation.

In the world of the khyaliya, remembering is a deeply creative act, and it’s an excellent sort of memory, working perfectly well in both directions.

environment India music: benefit concert

by Warren

2 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

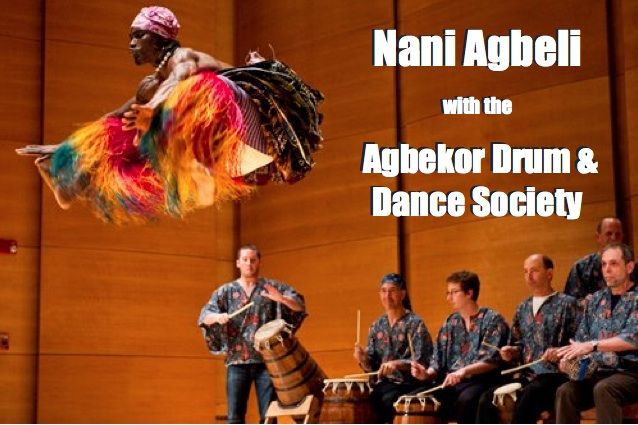

Dancing For The Planet

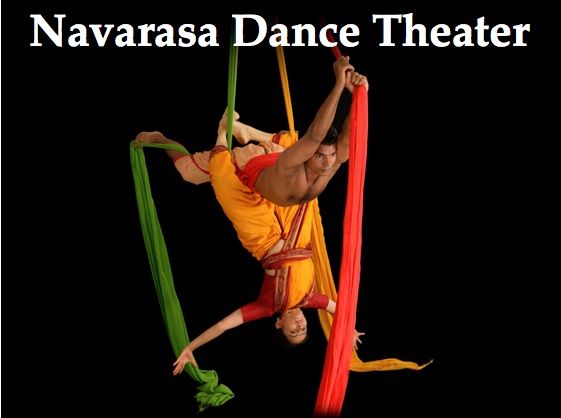

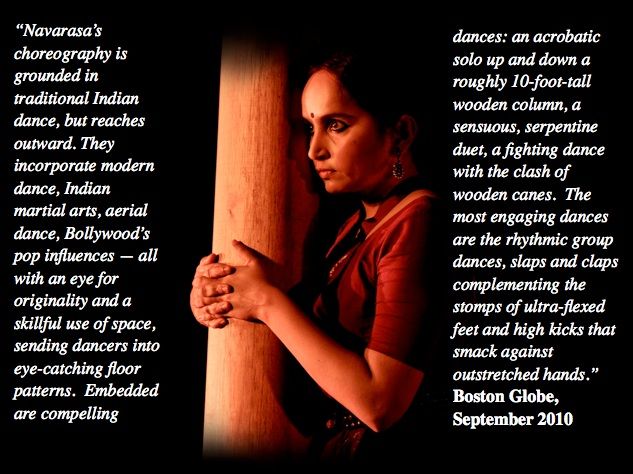

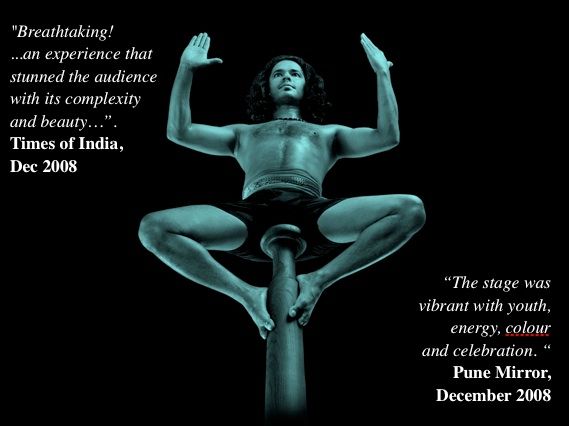

Navarasa Dance Theater

Nani Agbeli & The Agbekor Society

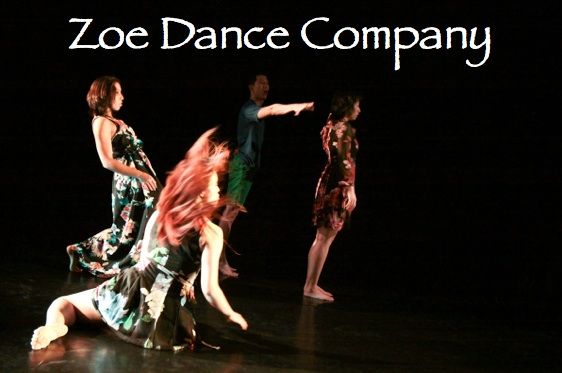

Zoé Dance Company

Friday, June 21 — 7:00 pm — Boston

On Friday, June 21, three dance companies representing diverse movement traditions will join together to draw attention to the global climate crisis. Featured artists are the Zoé Dance Company, the Navarasa Dance Theater, and Nani Agbeli & The Agbekor Society. The music begins at 7:00 pm, at Emmanuel Church, 15 Newbury Street, Boston, MA. Tickets are $20; $15 students/seniors. All proceeds will go to 350ma, the Massachusetts chapter of the environmental organization www.350.org. For information, please call 781-396-0734, visit “Dancing For The Planet” on Facebook, or send us an email.

“Dancing For The Planet” is the seventh concert in the “Playing For The Planet” series, conceived as a way for creative performers to contribute to the urgent struggle against global warming. Because the climate problem recognizes no national boundaries, the artists represent styles from three different parts of the globe. Their choice of beneficiary, 350MA.org, is focused on building global consensus on reduction of atmospheric CO2 levels — action which climatologists agree is necessary to avoid catastrophic outcomes. It’ll be an evening of brilliant dance and movement — for the central cause of our century.

Purchase tickets online from CCNOW:

Regular admission: $20

Student/Senior Admission: $15

Advance Ticket Orders Are Accepted Until 3 pm on June 21. Orders received after Tuesday, June 18 will be held at the door.

About the Artists

=======================================================

Navarasa Dance Theater was founded by renowned dancer/choreographer Dr. Aparna Sindhoor. Inspired by the eclectic performing arts traditions and boldly knitting together dance, singing, martial arts, and original music into seamless theatrical presentations, Navarasa’s multilayered, multilingual productions inspire, engage and entertain audiences around the world.

With original movement vocabulary created by choreographers Sindhoor and Anil Natyaveda along with theatrical narratives designed by S M Raju, Navarasa Dance Theater’s work is simultaneously specific and universal.

Navarasa Dance Theater has performed in North America, Asia and Europe and has been presented at various festivals and venues including the Bates Dance Festival, Lincoln Center (NYC), East West Players, LA and NJPAC, Jacob’s Pillow and Asian American Theater Festival, USA; Teesri Duniya Theater, Canada; Amol Palekhar’s Beyond Words Theatre Festival and Bahuroopi National Theatre Festival, India; and Franco Dragone’s INDIA show in Germany. With performing arts training schools in USA and India, Navarasa’s ongoing teaching programs include the “Dance for Everyone” project that offers scholarships and free dance training for underprivileged children and adults.

======================================================

Founded in 2002, Zoé Dance has presented works by Callie Chapman Korn, Ivan Korn, Emily Beattie and Meghan Ballog. Zoé Dance nurtures the art of dance, dance theatre and performance through accessible performance venues, educates the public and creates social awareness through themes explored in repertory, and has presented its work since 2002 in various venues and performance opportunities around Boston and internationally such as: World Music/CRASH Arts’ “Ten’s the Limit” (2005 and 2007), ArtBeat 2004 and 2009, “Virgin”, produced by the Dance Renewal Project, Harvard Square’s “May Fair” 2004, with the Choreographers Group 2004, Earth Dance’s Outdoor Performance Festival 2003, Corporación Cultural de Las Condes (Santiago, Chile) 2007, Boston Center for the Arts’ Mills Gallery as a featured artist of the Movement at the Mills residency.

Zoe has also presented its work at the Dance Complex, Cambridge Multicultural Arts Center, Tower Auditorium at Massachuestts College of Art, the Boston Common, Union Square Plaza, and Green Street Studios. Zoé Dance was awarded a project grant from the Somerville Arts Council (2010) and was a finalist for the Boston Dance Alliance’s Rehearsal and Retreat Fellowship (2009).

Callie Chapman Korn (artistic director): Callie holds a B.F.A. from the Boston Conservatory. With Zoé, Callie has presented her work in venues such as CrashArts‘ “Ten’s the Limit” at the ICA and Green Street Studios, Corporacion Cultural de Las Condes (Santiago, Chile), multiple self-produced concerts, festivals, part of the Dance Renewal Project’s “Virgin”, Dance Complex’s Shared Choreographers Concert. She currently dances for Prometheus Dance and has worked with artists such as: Nicola Hawkins, Karen Murphy and Emily Beattie. She has collaborated with video artists Greg Shea and Ken Kinna, composer Ivan Korn, and composers/musicians Pancho Molina and Billy Herron. Callie also helped develop the Dance Renewal Project and is currently the Marketing and Design Associate for the Boston Dance Alliance.

======================================================

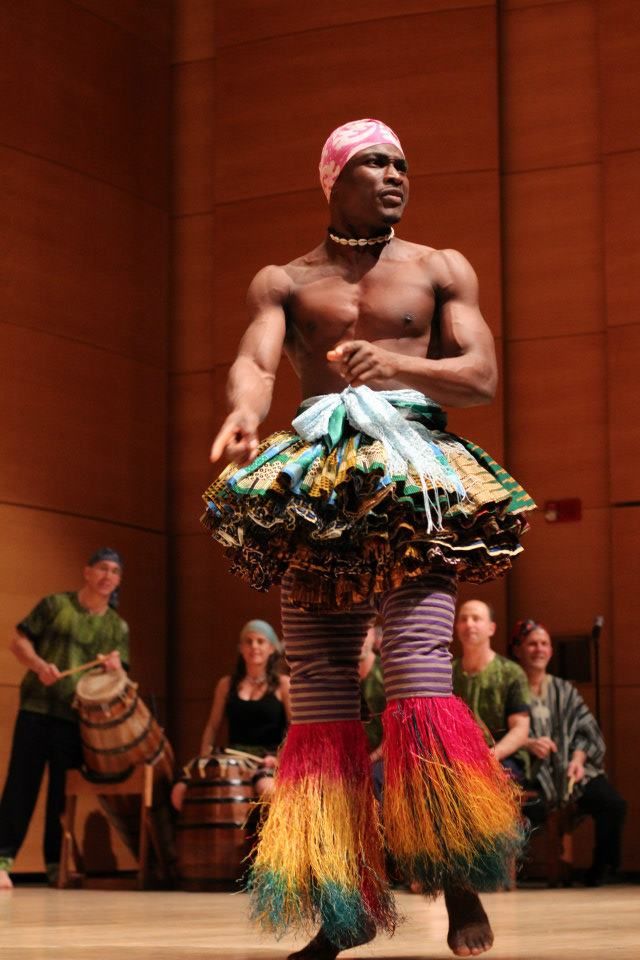

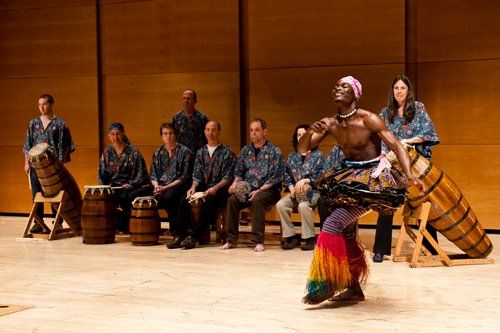

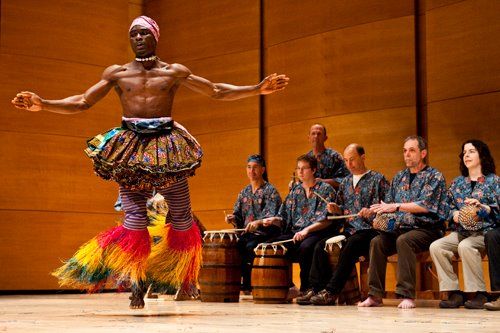

Known for his energy, athleticism, and precision on stage, the charismatic Nani Kwashi Agbeli is a native of the Ewe from the Volta Region of Ghana, W. Africa. He received his drum and dance training from his father, Godwin K. Agbeli, who was the chairman of the National Folkloric Company at the Arts Council of Ghana. Nani performed with and led the cultural group Sankofa Root II in Ghana where they received many awards.

For nine years, he served as the lead drum and dance instructor at the Dagbe Cultural Center, a school that trains domestic and international students in Ghanaian traditional arts, and is now on the faculty of the Music Department at Tufts University, where he and directs the Kiniwe Ensemble and teaches an integrated curriculum in the traditional singing, drumming and dancing of Ghana.

Nani also teaches Ghanaian dance and drumming at Brandeis University and Mount Holyoke College, along with Berklee College of Music, the Edna Manley School in Jamaica, Bowling Green University, and the University of Virginia, among others. He currently lives in Boston, Massachusetts.

The Agbekor Drum & Dance Society began in 1979 as a project to study and perform repertory from Africa, primarily focusing on two separate repertoires: Ewe and Dagomba. The homeland of the Ewe people is along the Atlantic Coast of western Africa in the nation states of Ghana and Togo. The Dagomba homeland is in savanna grasslands several hundred miles to the north and the lands of their traditional kingdom, Dagbon, are entirely within the current borders of Ghana. In Ewe drumming, each instrument has a specific rhythm that it repeats over and over. Riding on this musical wave, so to speak, the lead drum sends musical signals that cue dancers when to do their different variations. In Dagomba dance-drumming, four different drum parts intertwine their variations. In both Ewe and Dagomba traditions, each item of repertory has its unique purpose, meaning, history, and performance personality.

In their frequent collaborations with Ghanaian master drummers, the Agbekor Society continues to renew its connection with its African sources. The Society has appeared in clubs, concerts, lecture-demonstrations and festivals throughout New England, and in collaborations with jazz and “world music” artists like Natraj, Antigravity and the Jazz Composers Alliance Orchestra.

======================================================

About www.350.org and the number 350:

Co-founded by environmentalist and author Bill McKibben, 350.org is the hub of a worldwide network of over two hundred environmental organizations, all with a common target: persuading the world’s countries to unite in an effort to reduce global levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide to 350 parts per million or less. Climatologist Dr. James Hansen says, “If humanity wishes to preserve a planet similar to that on which civilization developed and to which life on Earth is adapted, paleoclimate evidence and ongoing climate change suggest that CO2 will need to be reduced to at most 350 ppm.” (Dr. Hansen headed the NASA Institute for Space Studies in New York City, and is best known for his testimony on climate change to congressional committees in the 1980s that helped raise broad awareness of the global warming issue.) Activists involved in the 350 movement include Rajendra Pachauri (Chairman, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), Vandana Shiva (world-renowned environmental leader and thinker), Archbishop Desmond Tutu (1984 winner of the Nobel Peace Prize and a global activist on issues pertaining to democracy, freedom and human rights), Van Jones, Bianca Jagger, Dr. James Hansen, Barbara Kingsolver and many more.

======================================================

Warren Senders is the contact person for “Dancing For The Planet.” He is one of thousands of concerned global citizens hoping to trigger positive change through social action and the arts. He can be reached at warvij@verizon.net or by telephone at 781-396-0734.

======================================================

“Dancing For The Planet” will be pleased to supply photographs and promotional materials for each of the artists performing at this event.

environment music vocalists: benefit concert

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Dean Stevens: Cuida El Agua

This guy sure can sing.

Come and hear him on April 19!

Purchase tickets online from CCNOW:

Regular admission: $20

Student/Senior Admission: $15

Advance Ticket Orders Are Accepted Until 3 pm on April 19. Orders received after Tuesday, April 16 will be held at the door.

When Did You Leave Heaven?

Big Bill Broonzy sings sooooo beautifully. Enjoy his careful phrasing and subtle guitar accompaniment on this film clip from “Low Lights and Blue Smoke.”

And on these songs, from the film “A Musical Journey: The Films of Pete, Toshi and Dan Seeger.”

Pete Seeger: “This is the last time Big Bill Broonzy ever sang. The following day he got operated on for cancer, and he didn’t have a voice from then on. This was a little place called Circle Pines Camp in Western Michigan, and that’s his own guitar he’s playing, he brought it with him. He said to me, ‘Pete, you got that camera with you?’ I had told him I wanted to film him sometime. I said, ‘Yeah, I have it with me.’ He says, ‘Well, you better film me now, I’m going to go under the knife tomorrow.’ ”

Irrelevant aside: I was at an LRY conference at Circle Pines Camp in August of 1975. Amazing.

environment music: benefit concert shakuhachi

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

A Solo Shakuhachi Against Climate Change

Here is the complete May 19 set by Elizabeth Reian Bennett. It’s taken a long time to get this up…but it’s worth it.

Enjoy:

Honte Jyoshi / Shizu No Kyoki

===============================

Oshu Sashi

===============================

Six George Street Melodies

===============================

Tsuki No Kyoku

===============================

If you enjoy this music, please consider making a donation to www.350.org