Education Indian music music: muscle training practice rhythmic cycles riyaaz tabla

by Warren

9 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Practicing Inside Rhythmic Cycles

One of the most challenging areas for many students of Hindustani music is working within rhythmic cycles. The ready availability of tabla machines has not solved this problem, because the core issue has more to do with not knowing how to practice than with not having a tabla player available all the time.

It is helpful to spend some time analyzing the various components of rhythmic-cycle practice. Once a singer begins this work, the cognitive load goes waaaaaay up; a lot more brain cells are required to keep all the elements of the musical equation under control. While holistic, gestalt-oriented practice is a must, it can be very helpful to break things down into smaller components and approach them with reductionistic ruthlessness.

To be competent in rhythmic-cycle-based improvisation, a singer must:

1 – be able to process rhythmic information concurrently with intonational information. That is to say, you have to be able to hear and feel the beats without getting distracted by them to the point that you go out of tune.

2 – be able to recognize important beats in the cycle and recalibrate according to position. That is, you have to hear crucial structural points and have enough cognitive strength available to lengthen or shorten your melodic line if necessary.

3 – be able to make coherent melodic shapes of specific lengths. In performance, it’s not enough to start an improvised melody at a specific point in the rhythm and finish it at another point — the melody you’re making needs to make sense. And (as if that weren’t enough) it needs to make sense at several levels; it has to be correct in raga terms, and it has to have gestural integrity. Those two are emphatically not the same thing.

Let’s take those distinct skills in turn, and I’ll discuss some ways of approaching them in the course of your practice.

Processing rhythmic and pitch information simultaneously.

One of the factors in developing this skill is that the percussive sounds of the tabla are at first a distraction, taking your limited attention away from the pitch dimension. So the way to work with this is to turn on your tamboura and your tabla machine…and then set the tabla at an almost inaudibly low volume. It should sound like somebody playing in the building next door. Of course, at that level, you won’t be able to recognize beats, but that’s not the point of this exercise.

With the tabla turned down as low as possible, sing freely. Sing slow alap, making sure you’re in tune, and making sure you’re not distracted. Take a long time doing this practice; it can be part of your daily routine for months.

Every so often, sing a long tone, and while you’re singing, train your attention on the sound of the tabla. Can you listen to the distant tapping of the drums without losing your intonational focus? Practice shifting your attention back and forth between your long tones and the sound of the tabla.

Put your hand on the volume control of the electronic tabla, and try turning it up very slightly while you’re singing long tones — and then back down again. Attempt slightly more involved lines in the raga/scale of your choice (an easy one is best; keep the cognitive load as low as you can) while shifting the tabla volume freely.

Another approach to this is to turn on your tamboura and tabla machine (at full volume) — and do domestic tasks. Don’t sit down; don’t practice. Let the tabla be part of the background environment. Do the dishes or the laundry, and every so often, sing a snatch of melody.

Eventually you’ll be able to ignore the tabla when you need to focus on what you’re doing in melody-space.

Which brings me to the next necessary skill:

Recognizing important beats, and recalibrating according to position.

If you haven’t already read my advice on theka recitation, you can find it here. Clear and flowing recitation is hugely important for beat recognition. Once you’ve developed a good spoken tabla sound, try recording your own voice reciting theka for a few minutes, and use this recording instead of your tabla machine to accompany your practice. Hearing your own voice providing theka is hugely useful. Use sound manipulation software to make an accompaniment recording that’s as long as you need it to be.

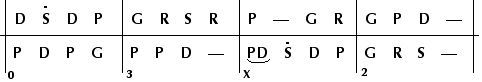

If you have a practice partner, switch back and forth between reciting theka and singing a simple composition. Here is a sargam composition in Raga Bhoopali that is admirably uncomplicated.

While you sing the melody, your partner recites theka; then switch.

Practice singing only fractions of the melody: the first half but not the second; the second half but not the first. Sing from the 13th beat through the 4th beat, leaving beats 5-12 open. Make up other combinations of singing and silence…all while your partner continues reciting theka. Switch frequently. When you’re not singing, listen carefully to the recited theka — don’t let your attention drift!

Sing from khali to the sam, then from the 10th beat, the 11th beat, the 12th beat, etc. Practice each combination of singing and silence multiple times. Getting it accurately once is not enough; you need to be able to get it accurately 85-90% of the time. When you feel comfortable with some of these combinations and can do them without mistakes, practice switching freely between two or three, while your partner recites. Then switch.

Then try doing this with the tabla machine. Play with your ability to pay attention to the rhythm at different volume levels; occasionally practice the ignoring-the-tabla activity discussed above for a little while…and then return to the compositional activity.

As you do this, you’re gaining facility in switching from listening mode to singing mode and back again, while simultaneously getting better at correlating the bols of the theka with particular positions in the rhythmic cycle. That is to say, you’re getting better at figuring out where you are and recalibrating accordingly.

I’ll post more such exercises in the future. This is sufficient for the moment.

Let’s move on to the last area of competence:

Making coherent shapes within a set time-span.

A truly robust definition of “coherence” in a musical context is probably unachievable. For the moment, let’s agree that a “coherent melodic shape” is one which has a clear beginning, middle and end, which obeys the melodic rules of the raga, and which is rhythmically consistent throughout.

Notice that a lot of the shapes that meet this definition are, um, kind of dull. As they say in the computer industry, “that’s not a bug, that’s a feature.” Dull is good in this context. You are striving for coherence within a fixed time-frame, and at the beginning, that means simplicity above all else.

Here’s how to approach that process. Pick a time-span. For example, two complete cycles of tintal from khali to khali to khali. There is nothing inherently special about this one, it’s just the first one that came to mind. Here are some others:

One complete cycle, from beat 13 to beat 13 — and joining the last 4 beats of the mukhda;

One and a half cycles, from sam to khali to khali — and joining the complete mukhda;

Three-quarters of a cycle, from sam to beat 13 — and joining the last 4 beats of the mukhda;

Two and a quarter cycles, from beat 5 to khali to khali — and joining the complete mukhda;

One and thirteen-sixteenths of a cycle, from sam to khali to beat 14 — and joining the last 3 beats of the mukhda.

Pick a rhythmic value: two beats per note (BPN), perhaps. Pick a time-span that works (you can’t fit 2 BPN into 1 & 13/16 cycles, for example).

Begin with a basic arch shape — the default melodic gesture of Hindustani music. How many notes have to go up before you have to come down again? Make a melody that fits this stipulation. Remember, it should be dull. Don’t try for fancy, don’t try for twiddly, don’t try to do something that will earn daad from the invisible listeners in your head.

Eventually, try the same shape, but starting on a different scale-tone. Try a different shape. Try the same shape, but using a different rhythmic value. Once you get four or five different phrases memorized, practice moving from one to another — always, of course, with the appropriate version of the mukhda in between.

A similar exercise is very helpful in learning how to make meaningful melodic gestures inside vilambit cycles. Here, rather than working with specific numbers of beats, simply pick a length of time: 40 seconds, 32 seconds, a minute…and use a watch to time yourself. Make simple shapes that last precisely the stipulated length — and follow them with the mukhda of whatever vilambit piece you’re working on.

In these exercises, you are not involved in making art. You are teaching your muscles to measure time precisely.

Which is why it’s important to temper the time that you spend in this activity with time spent making art.

Don’t confuse the two activities. If you’re going to do art-making and muscle-training in the same practice session, get up and stretch in between; drink a glass of water. Change your posture; change the direction you’re facing — all of these will help you avoid accidental art-making when you’re muscle-training, and accidental muscle-training when you’re art-making.

When you’re making art, just try stuff. By now you’ve got a lot of stuff to try. See if you can get lost in the rhythm…and if you can get found again. See if you can make wiggly and unpredictable shapes. Don’t be afraid to make things that go out of tune or out of raag; fear of such an outcome is a potent inhibiting factor.

When you’ve done some art-making, think back on it. Remember areas where you were strong or weak. Strong areas don’t need as much focus in your next muscle-training session…but the pathway to mastery, as always, is in practicing the things you’re not good at.

Have fun.

Finally, a word on a related subject.

If you’re studying or teaching music, you’re engaged in the long, slow, work of taking parts of our past and preparing them to travel into the future.

Therefore, you owe it to yourself and to the music you cherish — to educate yourself about climate change.

No stable climate – no music. It’s as simple as that.

MUSIC IS A CLIMATE ISSUE

Hi iam learning to play E bansuri for last 7 years twice in a week of2hours duration. I am 1of the group of 30 student of varied level of skil.

My problem is of listening beats of taal while playing.

Thanks for the articles by both. I think i wiil be able to play properly with these exercisea.

THANKS AGAIN FOR SHOWING THE PATH.

ANIL MOGHE

very interesting and helpful

This is very interesting to me as a tabla player who provides accompaniment to vocalists. Not being trained in vocal music myself, I probably under-appreciate the sheer number of things the vocalist has to balance at any given moment. It seems to be easier for instrumentalists (e.g. sitar players) who can strum their chikari strings to keep time, vocalists have no such device to fall back upon.

This is indeed a fantastic resource. Thank you for making this publicly available.

Very fine practical tips Warren, appreciate the insights.

Also, much appreciate Abhinav’s and Vishwas’ comments.

Warren, thanks for an interesting article and Vishwas, thanks for very interesting thoughts on this topic.

I would like to add a few thoughts from my own experience that I believe are very useful to learn this skill –

1. Learn to listen to music while keeping track of taal as well as sur (i.e. counting every beat as well as recognizing every note being sung)

2. Getting sense of laya is much more fundamental than taal. Learn to keep track of laya before attempting to learn to keep track of the taal. This can be done in a stepwise manner. At first singing/playing jod is a good step followed by simply trying to sing in laya without bothering to keep taal while the taal machine is going. One is likely to suddenly find themselves singing/playing in taal.

Abhinav

Thank you !

This is very helpful. I can totally relate to feeling lost when a tabla player comes on. I tend to forget even things that I was previously comfortable with. This explanation is very insightful in breaking down this complex process into simpler components and exercises.

Thanks much !

Warren,

As I mentioned on facebook, I liked your elucidation of the learning process and the typical mental blocks one faces while trying to sing to a taala.

I have some random thoughts triggered by your blog that I may not be able to articulate as well as you have.

I realize that for a large number of music students learning from a good teacher for an extended period my not be practical or even possible so explanations like the ones you have offered become very important. But one caveat is that that sometimes, by explaining something very clearly, one tends to simplify and complicate it both at the same time. By making students conscious of all the faculties they need to commandeer while singing makes the process even more challenging than it is and also a bit unnatural.

First, one thing that is not realized is that a theka is not just a cyclic repetition of a set number of beats but has an ebb and flow, a set of phrases which make it somewhat equivalent to a purcussive melody. An indeed, tabla is a taal-vadya as well as a soor-vadya. This observation may be dismissed as being obvious but with the kind of thekas played by tabla palyers today, it is challenging to see this with slower thekas (vilambit) where the connection between the beats becomes more difficult to detect. To keep the phrases coherent is a challenge. But it is very easily discernible in good tabla *accompanists*, (not necessarily the same as good soloists)who are familiar with the musical aesthetics of the vocal style they are accompanying.

A properly played theka is of prime importance to Khayal singers; in fact, the teaching of vocal music is based on the presumption that an acceptable theka will be there, not just a count of beats. Unlike Dhrupad style, khayals need a theka. A dhrupad,on the other hand, can be sung on a taal alone with hand-claps (like in Carnatic music). And a theka although based on a taal, is not a taal by itself. e.g. Tilwada is a theka but is not a taal. I know you may be aware of this already but believe me, I am going somewhere with this.

Now, at least from my experience of having learnt from two Gwalior and two Jaipur gharana teachers and performing artists, raagas are taught primarily through representative phrases, which by themselves embody the rules of ascent, descent and signature patterns. Further these phrases have an intrinsic “laya” or tempo. A great deal of emphasis is placed on the proper enunciation of these phrases as it is otherwise difficult to impart the logic behind the rules. The phrases also lay bare the proper “uccharan” (musical pronounciation-not the same as pronounciation in diction) as many of north indian raags are based on “uccharan-bhed” or literally, differentiation through musical prounciation. This also distinguishes north indian music from carnatic. Mind you, these phrases are not rigid, not standardized but more organic and the intinsic laya I mentioned may differ from gharana to gharana or from musician to musician. The important thing is to know that it is there and to internalize it without being distracted by the these differences. Which is why learning from one teacher for a sufficiently long period of time is so important. Now, if properly taught and imbibed, alaaps become a natural extension by stringing together the phrases in a musically sensible sentence, or a melody. With regular practice and maturity, the student, out of his/her own need for novelty and expression, can apply his/her creativity in contructing new combinations, much like a student of oratory find ways of bending sentences either through changing the construction, richer vocabulary, etc. all in the persuit of enhancing the communication.

Interestingly, when singing on a theka, such students do not face much of a challenge as the intrinsic laya of the component phrases automatically fall in place with the laya of the theka. The only challenge that remains is to fit a meaningfully musical sentence within the space of the rhythmic cycle. With such training, even the “aamad” or the dovetailing of the alaap with the mukhda comes naturally and is not an awkwardly hurried abandonment of the alaap to catch the mukhda and “sama”. So properly trained singers actually derive strength from the theka rather than regarding it as a tightrope to be tread upon with extra care. Additionally, due to the intrinsic laya of the phrases, the entire alaap talks to the theka, intertwining itself with the beats (much like a vine with the branches of a tree) and not just meeting at the first beat.

Now if the phrases of the alaap acheive synergy with the phrasing of the theka, the alaap becomes more satisfying. This can be acheived by sometimes matching the two, or by contrasting or shifting them apart to create tension. Of course, the tension should be released by gracefully making them come back together at the first beat or “sama”. The tension and release is separate from that created through the melody itself, but both of these do feed off each other. If the synergy is sought through purposefully relating the two through extemporanous exploration (and some pre-meditated as well) and if the alaap is musically meaningful as in itself as well as in the context of the whole progression then the whole affair is elevated to an art, as opposed to just a technique.

An art form is easier to master if it is culturally relevant and provides an avenue to express oneself in the current cultural context. One thing I have observed is that the reason students, both in India and elswhere, find learning Indian classical vocal music disheartening is not due to the technical challenges involved but because of the challenge of trying to align themselves with the musical colloquialisms of a bygone era. It will be interesting to take the principles and techniques of indian vocal classical music and try to apply them to a more understandable context both in India and here in the West. And it may not -and need not- sound the same. Evolution of this kind has kept this classical form alive in India up until the last century. And every new form was challenged by the purists of its time. Today, although still alive and thriving in pockets here and there, indian claasical vocal music is in grave danger of becoming an antiquity and a curiosity if students and audiences lose interest due to lack of its relevance. Any art form that cannot enable you to express yourself in today’s language is doomed.

Vishwas

You have given a wonderful explanation of how to sing or play musical instrument with Tabla Taal. Even our highly experienced Guru tells the same thing in a different manner, but at times it becomes too frustrating when after umpteen number of trials also you miss the sum or khali. It is long process.