Jazz music: Billie Holiday genius

by Warren

2 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Billie Holiday, Just Because…

“The Blues Are Brewing” with Louis Armstrong

Billie Holiday (born Elinore Harris;[1] April 7, 1915 – July 17, 1959) was an American jazz singer and songwriter. Nicknamed Lady Day[2] by her friend and musical partner Lester Young, Holiday was a seminal influence on jazz and pop singing. Her vocal style, strongly inspired by jazz instrumentalists, pioneered a new way of manipulating phrasing and tempo. Above all, she was admired all over the world for her deeply personal and intimate approach to singing.

Critic John Bush wrote that she “changed the art of American pop vocals forever.”[3] She co-wrote only a few songs, but several of them have become jazz standards, notably “God Bless the Child”, “Don’t Explain”, “Fine and Mellow”, and “Lady Sings the Blues”. She also became famous for singing jazz standards including “Easy Living” and “Strange Fruit”.

Jazz music: genius Jazz Jon Hendricks vocalese

by Warren

1 comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Have Some Jon Hendricks To Take The Edge Off A Little

W/O.C. Smith — Lambert, Hendricks and Ross perform “Every Day I Have The Blues”

Jon Hendricks (born September 16, 1921) is an American jazz lyricist and singer. He is considered one of the originators of vocalese, which adds lyrics to existing instrumental songs and replaces many instruments with vocalists (such as the big band arrangements of Duke Ellington and Count Basie). Furthermore, he is considered one of the best practitioners of scat singing, which involves vocal jazz soloing. For his work as a lyricist, jazz critic and historian Leonard Feather called him the “Poet Laureate of Jazz” while Time dubbed him the “James Joyce of Jive.” Al Jarreau has called him “pound-for-pound the best jazz singer on the planet—maybe that’s ever been”.[1]

Jazz music: Eddie Jefferson genius vocalese

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Eddie Jefferson Makes Me Smile

Trane’s Blues

Eddie Jefferson (3 August 1918 – 9 May 1979) was a celebrated jazz vocalist and lyricist.

He is credited with having invented vocalese, a musical style in which lyrics are set to an instrumental composition or solo. Perhaps his best-known song is “Moody’s Mood for Love”, though it was first recorded by King Pleasure, who cited Jefferson as an influence. Jefferson’s songs “Parker’s Mood” and “Filthy McNasty” were also hits.

One of Jefferson’s most notable recordings “So What”, combined the lyrics of artist Christopher Acemandese Hall with the music of Miles Davis to create a masterwork that highlighted his prolific skills, and ability to majestically turn a phrase, in his style [jazz vocalese].

Jefferson’s last recorded performance was at the Joe Segal’s Jazz Showcase in Chicago and was released on video by Rhapsody Films.

Wiki

So What

The first time I heard his studio version of “So What” it just knocked me out. He captured Miles’ lyricism and openness perfectly…all the while singing a paean to the trumpeter. The live version is a bit faster, and Richie Cole plays great.

Here’s a studio recording from 1976 of “Sherry”

His voice is so full of warmth and welcome. I always felt that Eddie Jefferson was my friend.

Although there were a couple obscure early examples (Bee Palmer in 1929 and Marion Harris in 1934, both performing “Singing the Blues”), Eddie Jefferson is considered the founder, and premier performer of vocalese, the art of taking a recording and writing words to the solos, which Jefferson was practicing as early as 1949.

Eddie Jefferson’s first career was as a tap dancer but in the bebop era he discovered his skill as a vocalese lyricist and singer. He wrote lyrics to Charlie Parker’s version of “Parker’s Mood” and Lester Young’s “I Cover the Waterfront” early on, and he is responsible for “Moody’s Mood for Love” (based on James Moody’s alto solo on “I’m in the Mood for Love”). King Pleasure recorded “Moody’s Mood for Love” before Jefferson (getting the hit) and had his own lyrics to “Parker’s Mood,” but in time Jefferson was recognized as the founder of the idiom.

Jefferson worked with James Moody during 1955-1957 and again in 1968-1973 but otherwise mostly performed as a single. He first recorded in 1952 (other than a broadcast from 1949) and those four selections are on the compilation The Bebop Singers. During 1961-1962 he made a classic set for Riverside that is available as Letter from Home and highlighted by “Billie’s Bounce,” “I Cover the Waterfront,” “Parker’s Mood,” and “Things Are Getting Better.”

“Filthy McNasty”

Jazz music Personal: Robert Rutman Sun Ra

by Warren

11 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Hanging Out With The Man From Saturn

Several people have asked me to tell the story of my encounters with Sun Ra.

Over a span of about six or seven years, I caught Sun Ra and his Arkestra in Boston at least eleven times. While that’s not a lot by Deadhead standards, it’s probably more than I’ve seen any other musician live, with the exception of the great khyal singer Bhimsen Joshi.

To an alienated, jazz-obsessed teenager in Boston’s western suburbs, the knowledge that there was a bandleading madman who claimed to be from outer space was incredibly welcome. My high school library maintained subscriptions to a wide variety of periodicals — the usual suspects (Time, Newsweek, Life), some slightly more unconventional choices (The New Yorker, Ms.), and a few that were pretty bizarre. Of these last, there were three that made a huge impression on me: The Village Voice (where I first read about conceptual art, Nam June Paik and Charlotte Moorman), Source: Music of the Avant-Garde (where I first heard of Cornelius Cardew, Christo, Steve Reich and Alvin Lucier), and Downbeat (where I kept up to date on all the latest jazz happenings, and where I first learned of the existence of Sun Ra).

Jazz music: jazz vocals Mildred Bailey

by Warren

2 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Bessie Smith’s Overtones: Everybody Should Enjoy Mildred Bailey Every So Often

I acquired Henry Pleasants’ wonderful book, “The Great American Popular Singers” at Manny’s Books in Pune, where it rested, long-ignored, on a small shelf with other publications about Western music. The books on Indian music were in another section of the store; the only customer who went routinely to both shelves was me. I bought the book and began reading it in the rickshaw to Deccan Gymkhana. By the time I got home I’d learned things I never knew about Bessie Smith, Al Jolson and Bing Crosby (all of whom I’d heard, and heard of), and about Mildred Bailey, an unfamiliar name. Pleasants rhapsodized about her musicality, whetting my appetite.

Opportunities in India to hear Mildred Bailey’s music were nonexistent….so it wasn’t until a couple of years later that I found a 10″ lp in the collection of my friend Gene Nichols, and taped it for my own enjoyment.

And enjoyment was definitely what resulted. Bailey’s pitch, her sense of swing, her deceptive melodic simplicity, the subtlety of her ornamentation and phrasing…she sounded like a trumpet, or an alto saxophone.

Leonard Feather: “Where earlier white singers with pretensions to a jazz identification had captured only the surface qualities of the Negro styles, Mildred contrived to invest her thin, high-pitched voice with a vibrato, an easy sense of jazz phrasing that might almost have been Bessie Smith’s overtones.”

(Feather — The Book of Jazz)

Or, as Leonard Feather says, like Bessie Smith’s overtones.

Thanks for the Memories

Jazz music Warren's music: Chazz Rook Jazz Composers Alliance Orchestra Mingus

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Chazz’ Mingus Story: A Composition for Jazz Orchestra and Two Speaking Voices

I write music for the 20-piece big band run by Boston’s Jazz Composers’ Alliance. The JCA Orchestra does several concerts a year (recently we’ve had some Sunday club dates at Johnny D’s, in Somerville, MA, which is really a blast), always featuring writing by all the composers in the collective. I am one among many, the seniormost being the Alliance’s founder, Darrell Katz. You can find out more about the Jazz Composers Alliance here.

In 2007 we decided to present a “tribute concert,” where we’d undertake to give our impressions of the music of three important jazz composers: Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, and Charles Mingus. After some dithering, I decided to develop a piece on Mingus. Notice the preposition. I did not want to do an arrangement of a Mingus tune; while I enjoy arranging other people’s music, I had an idea in mind.

One of my oldest friends is a sarod player, an American whom I met in the early years of my study of Indian music. His given name was Charles Rook, but he was known to one and all as “Chazz.” When I asked him how he’d gotten the name, he told me a long and amazing story about his relationship with the great bassist and composer. Since that time (in the mid-70s) I’d heard him tell it over and over, and I’d had it told to me by other mutual friends (“You know Chazz’ story about Charlie Mingus? No? Well…”). So I knew the outline pretty well.

Chazz Rook, visiting Pune in 1987

Jazz music: Jazz Jon Hendricks Mel Torme Scat singing

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Mel Torme is Amazing

Here’s Mel doing two terrific duets, the first with Jon Hendricks, the second with his son Steve.

Torme’s intonation, voice production and melodic imagination are a joy to the ear. I particularly enjoy his work with Hendricks, which seems a little raw-er, a little looser.

Jazz music: genius thomas quasthoff

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Thomas Quasthoff

The extraordinary Thomas Quasthoff, singing improvisations on Miles Davis’ All Blues. One of the interesting things about this is that since he comes from a classical background (although he’s apparently loved and enjoyed jazz his whole life, which is pretty obvious from this performance), his handling of this piece has not a whiff of the “doing-a-standard-that’s-been-done-to-death-already” atmosphere which you sometimes find in the work of hipper-than-thou musicians who wouldn’t be caught dead singing something as hackneyed as, say, All Blues.

Or, for that matter, My Funny Valentine.

Education Jazz music: charlie banacos obituaries

by Warren

2 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

The Harmonics of Intensive Care: Charlie Banacos, R.I.P.

One of the country’s greatest music teachers died yesterday. Charlie Banacos taught jazz theory and ear-training for decades from his Massachusetts home; his students include many of the most famous names in jazz music.

His students have performed or recorded with Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Maynard Ferguson, Chick Corea, Wynton Marsalis, David Liebman, Wayne Shorter, Michael Brecker and Joe Henderson, among others.

I never studied with Charlie, although many friends and colleagues did. Most importantly for me, the man who taught me most of what I know about jazz was a long-time student of his, so although we never met, I am part of his pedagogical lineage.

But that’s not what this post is about. When I heard about Charlie’s death (through a post on Facebook) I went to the “Charlie Banacos Students” FB page to learn more. And there I read a post called “Email from Charlie.”

Education Jazz music: Charlie Haden Dewey Redman Edward Blackwell Harmolodic Concept improvisation lecture-demonstration Ornette Coleman

by Warren

9 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

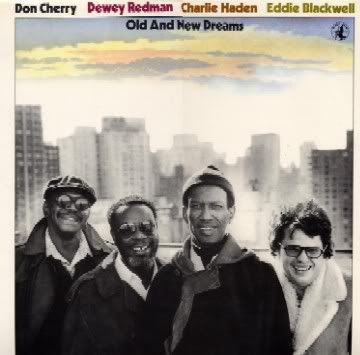

The Old And New Dreams Band: A Lecture-Demonstration

The first Old and New Dreams record on Black Saint has long been one of my Desert Island Discs. The rhythm section of Charlie Haden and Ed Blackwell serves up a magnificent polytextural stew in support of the melodic initiatives of Don Cherry and Dewey Redman; everybody plays brilliantly throughout.

In many ways, the work of this band always struck me as a purer presentation of Ornette Coleman’s concepts than many of Ornette’s performances. I mean by this that the shifting tonalities and re-centerings of melodic structure that are at the heart of Coleman’s work are in many ways easier to hear when the composer’s unique alto saxophone sound is not present. Ornette’s sonic presence is undeniable, but when he’s not there it becomes easier to think of the Harmolodic approach as a system that can be used by other musicians. When Ornette’s concept is used (and, as we hear below, explained) by other players, it is easier to separate the things they play from their performance personae. Ornette is such a dramatic and eccentric figure that it is tempting to explain Harmolodics as a species of musical crankery. When Don Cherry, Dewey Redman, Charlie Haden and Ed Blackwell interpret his music and influence, the importance and essentiality of Coleman’s Harmolodic Concept is indisputable.

They came to Harvard University in 1980 and played, if memory serves me correctly, at the Loeb Drama Center — an unusual venue. Hearing the band perform live in Cambridge was a truly wonderful experience; some memories from that gig still stand out (like watching Ed Blackwell create a huge blanket of rhythms without, apparently, moving his hands at all). I heard them again at a Cambridge jazz club (Jonathan Swift’s? I forget) a few years later, and they were brilliant then, too. But I digress.

One of the most memorable features of their time under Harvard’s auspices was the lecture-demonstration that Cherry, Redman and Haden gave at Adams House on February 29 (Blackwell was unavailable due to medical issues; IIRC he was doing daily dialysis). I recently digitized the recording of that lec-dem (made on a lo-fi boombox belonging to the drummer and drum-maker Betsy McGurk, who can be heard asking a few questions in the Q&A portion of the presentation) and I’m happy to present it here, along with a transcription (the result of many enjoyable late-night hours).

I have my own thoughts on what Ornette’s “Harmolodics” is all about (the fact that Ornette uses the word “love” a lot when he talks about his music theory is an interesting clue) and someday I’ll write them down and put them out here…but for now, here are Don Cherry, Dewey Redman and Charlie Haden, talking and playing about their music and their mentor, Ornette Coleman. Enjoy.