Indian music Jazz music Personal: concerts

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Brief Update…

…”Violins Against Climate Change” was a spectacular success. We sold out the hall (actually running out of chairs!) and raised a whole buncha money for 350.org. I will be posting videos and photos this week.

India Indian music Jazz music Personal: ektaal form musical conception

by Warren

1 comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Some Thoughts on Rhythmic Cycles and Form

In late 1994 I was invited to give a lecture-demonstration on “world music” to a local cultural society in Pune. I talked about the similarities and differences in structure, conception and aesthetic values between, principally, Hindustani music, Ghanaian music and Jazz (since these are the musics I know best and love most); Vijaya and I demonstrated some ideas and patterns from these idioms, and I played a lot of examples from our collection.

For instance, I wanted to demonstrate how a jazz standard is used as the starting point for improvisation — so Vijaya sang “Body and Soul,” accompanying herself on guitar, and then played Coleman Hawkins’ version, which seemed to go over big.

Lecture-demonstrations are hard to predict, and the fellow who’d arranged this one had invited quite a few of his Hindustani rasika friends. For the most part they listened carefully, nodding appreciatively and making sage remarks sotto voce during our singing. Toward the end of the two-hour program, I started taking questions, and P______ B_______, an elderly vocalist, stood up. His question went more or less like this:

“All of these examples you have played us, they are all in medium or fast speed. Isn’t it true that only in Hindustani music do we have the vilambit tempo?”

This was another manifestation of the “only in India” concept, and as with all such, an answer requires considerable care in order to avoid either error or offense.

I asked him: “When you listen to a khyal in vilambit ektaal, do you actually count beats so slowly? One every five seconds?”

Immediately there was a corrective tumult. Nobody, it seemed, wanted me to believe that they really felt a pulse that glacial; several people fell over themselves in their eagerness to disabuse me of my misunderstanding, and began reciting the rhythm syllables of a vilambit cycle, showing me its internal subdivisions.:

Audience members: “No, no! Of course not — each beat has divisions, like te — re — ke — ta —…”

Warren: “So in vilambit ektaal, each beat is actually a larger unit, not a pulse you actually feel?”

Everybody agreed that this was so.

Warren: “So, a vilambit ektaal cycle is basically a kind of framework that forces the singer to organize his ideas in time, and fit his improvisation to the structure?”

Audience members: “Yes, yes, exactly!”

Warren: “But somebody who knew nothing of Indian music could listen to a vilambit ektaal piece, hearing only the subdivisions, and might not understand how the larger structure is outlined?”

Also yes.

Warren: “This is exactly what happens when you listen to our jazz pieces. In much music of the jazz tradition, there is a basic laya, which moves at a comfortable tempo and is maintained by the drums — and there is another rhythm, which moves much more slowly, and is maintained by the piano by changing harmonies according to a preset structure. Because you are used to hearing the large structure played by the tabla, you find it difficult to understand a large structure outlined by a totally different instrument.”

Well, the dialogue went on and on, and I’m not sure if I convinced anybody. After all, they sure didn’t hear any large structure in Hawk’s “Body and Soul!”

But the point I’m getting at is that all musical cultures have some way of organizing their performances in larger time-frameworks, and that we won’t find them by looking (or listening) where they’re not. Both khyal singing and traditional jazz of Hawkins’ ilk rely constantly on large-scale structures; the first articulated by tabla, and called the tala, the second articulated by piano, guitar or other harmonic instrument, and called, well, “the form.” Western musicians have adopted the generic term “form” to denote any structural constructs which guide a performance over time: “Repeat the first four bars of the A section under the sax solo, but play the bridge straight through” is a statement of form, as is “When the minuet begins, let’s remember to keep the tempo steady until we begin the decelerando at bar 37,” as is “Hey, let’s have a couple of choruses of guitar solo!”

In singing a khyal, by contrast, the form is the rhythm, writ large. Note the following example, and note it well, for it embodies a crucial principle:

Ektaal is a pattern of strokes played on the tabla; the same strokes, played in the same order, over and over and over. In fast and medium tempi, ektaal is a pleasant 6-beat or 12-beat groove, very catchy, easy to follow, each beat perhaps a third or quarter of a second; I just listened to a performance of madhya (medium) ektaal in which each complete rhythmic pattern took around four seconds to complete. When it’s performed in vilambit, however, ektaal’s drum strokes now occur once every four or five seconds — each cycle taking perhaps just under a minute!

A groove slowed down by a factor of twenty becomes an important form for improvisation in khyal. Now that’s an expansion of time!

Jazz music vocalists: genius

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

The Man Who Made James Moody “James Moody”

Here’s a little classic from King Pleasure:

Jazz music vocalists: genius

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Without Music…

…why go on?

Have some Sheila Jordan. Steve Elman introduced me to her music years ago and I have always been a big fan of her work. She never over-sings…and always communicates perfectly.

A tribute to Billie Holiday

Sheila Jordan grew up in Summerhill, Pennsylvania before returning to her birthplace in 1940/41 playing the piano and singing semi-professionally in Detroit clubs. She was influenced by Charlie Parker and was part of a trio called Skeeter, Mitch and Jean (she was Jean) which composed lyrics to Parker’s Arrangements. Sheila also claimed in her song “Sheila’s Blues” that Charlie Parker wrote the song, “Chasing the Bird” for her, as she and her friends were known to chase him around the jazz clubs in the 1940s.

In 1951 she moved to New York and started studying harmony and music theory taught by Lennie Tristano and Charles Mingus. From 1952 to 1962 she was married to Charlie Parker’s pianist Duke Jordan.

In the early 1960s she had gigs and sessions in the Page Three Club in Greenwich Village, where she was performing with pianist Herbie Nichols,[3] and was working in different clubs and bars in New York.

In 1962 she was discovered by George Russell who did a recording of the song “You Are My Sunshine” with her on his album The Outer View (Riverside). Later that year she recorded the Portrait of Sheila album (recorded in September 19 and October 12, 1962) which was sold to Blue Note.[4]

Wiki

1992. Her brilliant duet with bassist Harvie Swartz: “Let’s Face The Music And Dance,” “Cheek to Cheek,” “I’ve Grown Accustomed to (the Bass).”

I greatly enjoy her handling of folk and traditional material. This is her version of “The Water Is Wide.”

Ornette Coleman…

…is a genius.

His “Harmolodic Ballet,” titled “Architecture in Motion.”

I wish I knew who the tabla player was.

environment Jazz June 12 Action music vocalists

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Dominique Eade’s Set (excerpt)

Because of technical issues, only these two tunes from Dominique Eade’s wonderful set at the “Singing For The Planet” concert are available. She is accompanied very sympathetically and supportively by Will Graefe on guitar and Will Slater on bass.

Here is her version of Hoagy Carmichael’s “Buttermilk Sky,” a song which I’d never heard before.

This is her original piece, called “The River.” She begins with some nice singing and kalimba:

The other performances from “Singing For The Planet” can be found here:

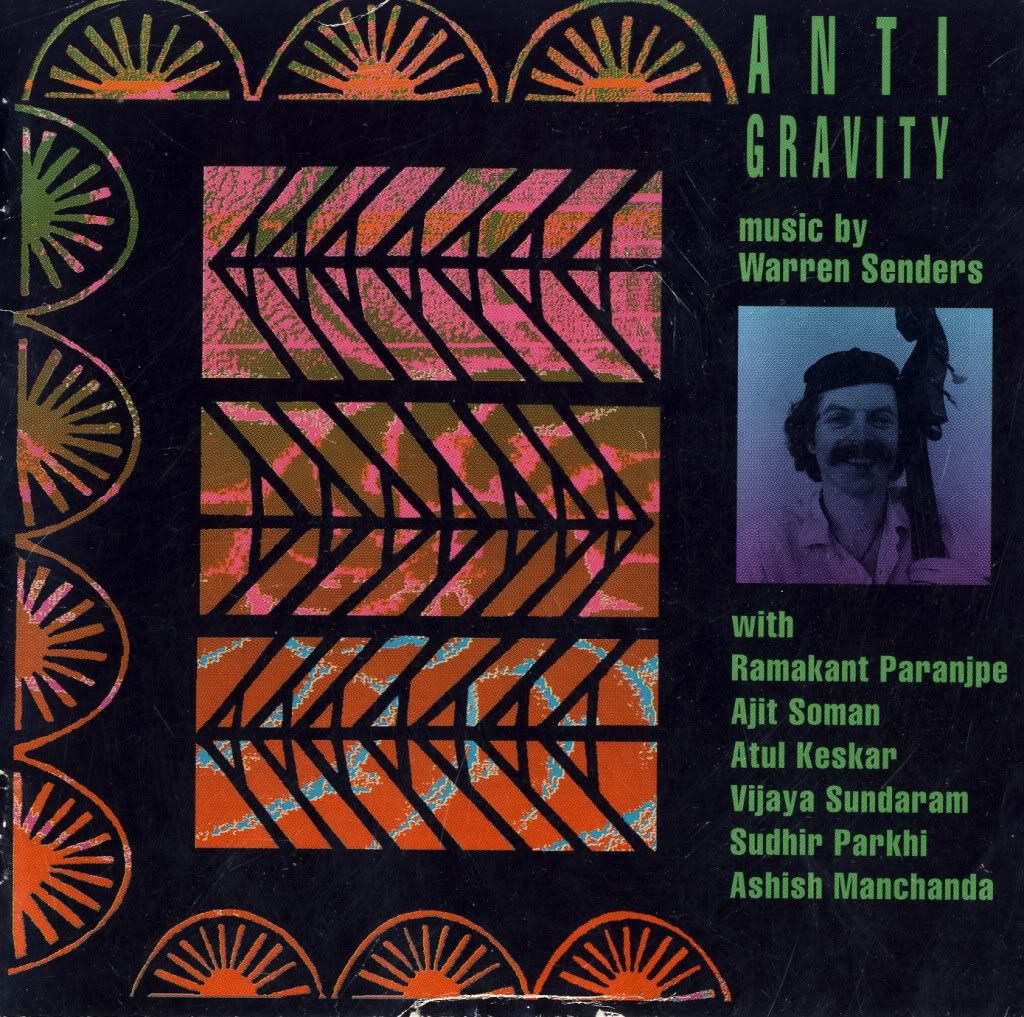

India Indian music Jazz music Warren's music: Ajit Soman Antigravity Ashish Manchanda Atul Keskar Indo-Jazz Ramakant Paranjpe Sudhir Parkhi Vijaya Sundaram

by Warren

4 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Antigravity — The Indian Group, 1990-1991

Here are the pieces which make up the first Antigravity CD, released as “Antigravity — The Music of Warren Senders” (Accurate AC-4307), along with scans of the complete CD booklet & tray card. These were recorded at Ishwani Kendra Studios in Pune in 1990 and 1991.

This has been out of print for years. I only have a few mint copies left.

more »

environment Jazz June 12 Action music vocalists: jazz vocals Latin Jazz Mili Bermejo

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Singing For The Planet: Mili Bermejo’s Set

Here is the complete set by Mili Bermejo and her trio: Dan Greenspan – bass, and Doug Johnson – piano.

They began with a bass/voice duet:

Te abrace en la noche , by Fernando Cabrera

Noche, by Nando Michelin

environment Indian music Jazz June 12 Action music photoblogging Warren's music: Mili Bermejo Singing For The Planet

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

A Quick Report on the June 12 Concert

The “Singing For The Planet” concert happened as planned last Saturday. We had an excellent crowd and raised a little over $800 for www.350.org — and the music was lovely.

Mili Bermejo, Dominique Eade and Me

I’m just putting a few photographs up for now. A full report with video will go up later this week. These images are courtesy of Hadley Langosey, and there will be more to come.

Dominique, Will Slater, Will Graefe, some guy, Harriotte Hurie, Mili Bermejo, Dan Greenspan, Priti Chakravarty, Akshay Navaladi. Missing: Doug Johnson

First Set: The Mili Bermejo Trio

Mili Bermejo with Doug Johnson on piano and Dan Greenspan on bass

Second Set: Warren Senders & The Raga Ensemble

Me, with Akshay Navaladi, tabla; Priti Chakravarti, harmonium; Harriotte Hurie, tamboura.

Third Set: Dominique Eade & Friends

Dominique Eade with Will Slater on bass and Will Graefe on guitar.

Profile: Dominique Eade

I first heard Dominique Eade sing around 1980, when Matt Darriau and I had put together a short-lived big band. She sang on one or two of the charts, and I was bowled over by her musicianship. I still am, and I find it amazing that we have not shared the stage since then. Thirty years, huh?

This post duplicates the information about Dominique on the “Singing For The Planet” page, but it includes some music. Listen. She’s an extraordinary artist.

About Dominique Eade

Since her arrival in Boston in the late 1970s, vocalist and composer Dominique Eade has stood out as a musician of exceptional quality. Combining conceptual daring with superb technique, she has won admirers around the world for her fearlessness and artistry.

Dominique Eade — “Go Gently To The Water”