India Indian music music vocalists: genius Jaipur Gharana khyal

by Warren

9 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Singing Is Nothing But Joy: An Appreciation of Mallikarjun Mansur

The first time I heard the music of Pandit Mallikarjun Mansur was in 1978, very early in my study of Hindustani music. I’d taken a survey course on Indian music at the Harvard Extension, and the professor gave me an assortment of vocal music that included Mansur’s rendition of a beautiful rainy-season raga, Gaud Malhar.

It was strikingly different from the other music on the tape. More than any of the other singers represented, this vocalist really seemed to be enjoying himself. There was a rhythmic playfulness that spoke to my jazz-loving self, integrated with the serene aesthetic flow that characterizes Hindustani music. His voice was a high, slightly raspy tenor; his range was relatively narrow; his breath control preternatural.

I asked other people about Mansur. This was the late 1970s, and most of the people I knew in the Indian music community had never heard of him; as it turns out, he had not been performing widely for decades and had only recently returned to the notice of the concertgoing public in India. Over the next few years I gradually acquired tape recordings of his LP records, whetting my appetite for more of this remarkable singer’s remarkable music. Nobody I knew on the Indian tape-trading network had any concert recordings, and the Internets hadn’t been invented yet.

He did not clothe himself in princely robes. He did not care to be the center of attraction. He was content to be inconspicuous. He continued to look like a shopkeeper’s accountant. He did not speak like an oracle. He rarely referred to his triumphs. He won not only the respect but the affection of his contemporaries. He was wholly without envy. His was an unfailing geniality and lightness of heart. His airs were what he sang. He did not put on any.

— H.Y. Sharda Prasad —

The music we’ll be hearing is from the tradition of khyal singing, the most popular form of vocal classical music in North India. There are thousands of khyaliyas throughout India and the world. In almost any area with a significant Indian population there will be people who study, teach and perform khyal.

It’s a highly improvisational genre; the very word khyal literally means “imagination.” Singers are expected to generate new material inside flexible melodic structures called raga-s, with performances lasting for many hours.

All khyal performances have a basic structural model in common. Here it is:

Sing a song. It can be a short song or a long song, a slow song or a fast one. Paradoxically, the slower the tempo, the fewer words in the song; some pieces in ultra-slow tempo may have only five or six words stretched over a minute of melody.

The first word or words of the song are rhythmically set to coincide with an important beat played on the tabla drums, which play a continuous, repetitive cycle of beats (which can be slow or fast along a considerable range of possible tempi).

After singing the song once or twice, the khyaliya begins to make variations — each time returning to those first few words and the important beat. Each successive cycle features more elaborate improvisations, and a more interesting and nuanced return to those first few words and the important beat. As the performance goes on, the amount of melo-rhythmic content that gets crammed into each rhythmic cycle increases dramatically, but without exception there’s going to be a return to those first few words and the important beat. At some point there’s another set of song lines that go into the upper register, and the singer will spend some time up there using a different way of resolving her/his ideas — but eventually that, too, will come to a conclusion…by returning to those same first few words and that same important beat. By the end of the performance, the material incorporated into the improvisations is intricate (arguably the most intricate of any vocal genre in world music), self-referential (you do notice how these sentences work, don’t you?), and convoluted (with the musical equivalent of (occasionally even (multiply) nested) parenthetical clauses showing up regularly) — in short, a dazzling display of virtuoso technique and musical imagination (assuming, of course, that you’re listening to one of the great ones, which (if you’re listening to the musical examples that accompany this essay) you are) that invariably winds up resolving neatly on those first few words and that important beat.

Whew.

—————————————————

Live in New Delhi, 1985

—————————————————

It wasn’t until after I went to India in 1985 that I first heard Mansur sing at full length. It was in November of that year; I had business to attend to with the organization that administered my fellowship, so I needed to go to Delhi. Bhimsen Joshi and several members of his family were also headed North; he was to sing as part of a weekend-long music festival at Delhi’s Siri Fort Auditorium. That was the first time I was part of Bhimsenji’s “entourage,” an experience in itself. I was excited to learn of the other participants in the concert series: in addition to Bhimsenji’s performance, we were to hear the great shehnai virtuoso Bismillah Khan, the brilliant violinist N.Rajam…and Mallikarjun Mansur, on Sunday morning.

And I was sitting in Siri Fort Auditorium on December 1, 1985, when Mallikarjun Mansur came out on stage, sat down, and completely blew me away.

There are many different styles of khyal. All share the basic ensemble: a voice, a drum, a drone, and a melodic accompaniment that echoes the singer’s lines. The traditions differ in repertoire and in approaches to improvisation, with individual artists maintaining personal styles within the “sub-genre.” Singers may have highly idiosyncratic ways of combining notes, of ornamenting passages, of articulating words, of intoning — and all of these combine to mark an artist as an individual. Some khyaliyas are highly original artists, some are formally correct grammarians, authoritative but uninspiring, and some are frankly derivative, either of their own teachers’ approach or that of a charismatic performer like Bhimsen Joshi.

Mallikarjun Mansur was pretty clearly an inspiring original. His singing that day in Delhi completely floored me. Good thing I had a tape recorder.

By the time he’d been singing this piece for 20 minutes or so, his imagination was in astonishing flower. The incredible burst of undulating melody at around 4:20 in the final video is a type of line known as a gamak taan. You can hear the audience’s rapturous response before he moves briefly to a shorter, faster piece in the same raga.

Over the ensuing years I found out more about Mallikarjun Mansur, learned to appreciate his music, learned some of the songs he presented, acquired quite a collection of his recorded performances, and heard him perform live two more times.

Let’s listen to some singing. Here’s a pair of videos made at a concert quite close to the end of Mansur’s life. His enthusiasm and artistry are quite undiminished by age:

Raga Sughrai:

Raga Kafi Kanada & Kafi:

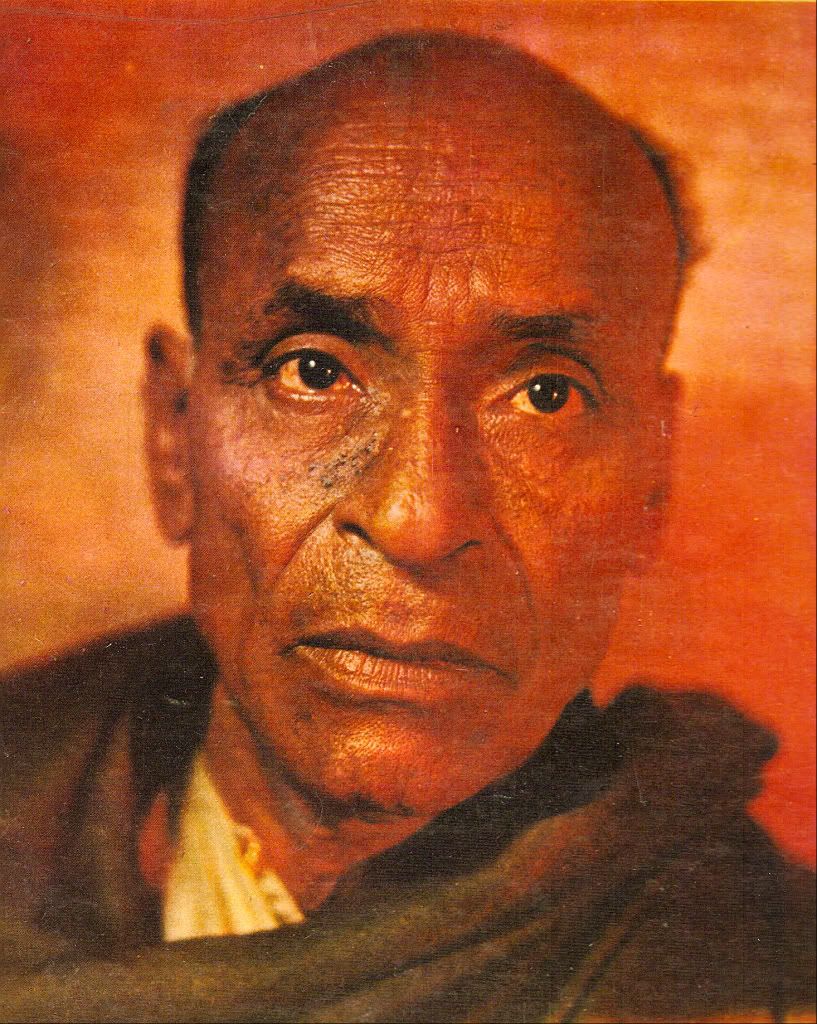

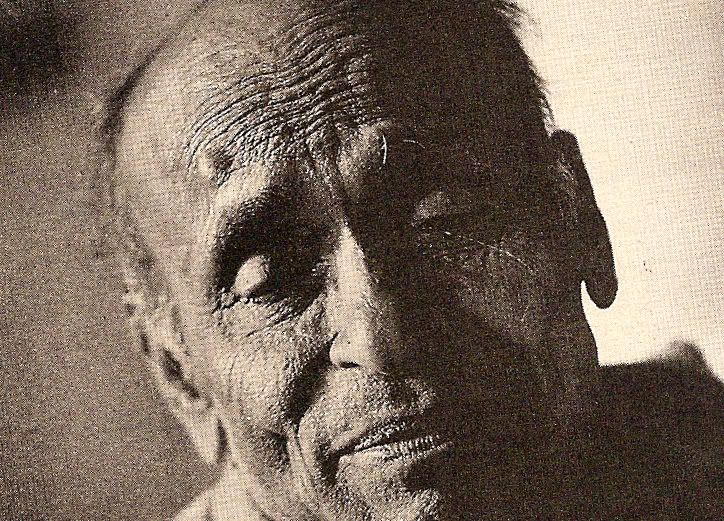

His first recorded music was in the 1930s, when he made a number of 78 rpm discs, including this lovely version of the cheerful pentatonic raga Durga. Enjoy his scintillating improvisations and his ingenious ways of returning to the first few words of text (“Chatur sugara,” a reference to the clever and beguiling Lord Krishna).

Mallikarjun Mansur: Raga Durga

As a young man.

In this pair of videos made at a private morning concert, he’s accompanied by his son Rajashekhar Mansur. You can hear the younger man’s voice continuing his father’s ideas, sustaining long tones and maintaining the flow of melody. While the video quality is wretched, the audio is fine — and the music is sublime.

Raga Bhairav:

The songs of Hindustani classical tradition are in an archaic dialect of Hindi known as Braj (which bears the same relationship to modern spoken Hindi as, say, Elizabethan English to the speech you’ll hear on the streets of London or New York). However, Mansur’s mother tongue was Kannada, a South Indian language. Devotional songs in this language are known as Vachanas. As with any song where the text is of paramount importance, there is relatively little melodic or rhythmic variation — but enjoy the passion and expression that Panditji brings to his rendering:

When an Indian classical musician is introduced to an audience, there is an important preliminary step. Unless the artist is very well-known (and often even then), the compere is expected to provide as much detail as possible about her or his training. To have learned from an important teacher is a point of pride, and the recitation of a singer’s “pedigree” gives the listeners a much clearer sense of what to expect.

Thus, when an educated listener reads a paragraph like this one, it conveys a great deal of information:

“Born at Mansur, in Dharwar district, Karnataka State, Mallikarjun Mansur was initiated into the mysteries of Hindustani music by Pandit Neelakanth Buva Alurmath, a disciple of the Gwalior maestro, Pandit Balkrishna Buva Ichalkaranjikar. After six years of rigorous studentship with this veteran, he sought further training from Ustad Manji Khan and Ustad Bhurji Khan, the gifted sons of Ustad Alladiya Khan. Rigorous discipline and patient practice under the guidance of the two ustads groomed young Mansur to become one of the ablest exponents of a difficult singing style…”

Liner notes for INRECO 2411-5094, “Morning and Evening Ragas from Pandit Mallikarjun Mansur”

I’m going to unpack that dense mass of factual tissue for you.

The singer’s last name is the same as that of his hometown; it is often the case in India that one part or another of an individual’s name will reveal his or her “native place.” Dharwar (also called Dharwad) is a small city in Karnataka State which has provided many of India’s greatest musicians.

Mansur’s first teacher was Neelakanth Buwa Alurmath. “Buwa” is an honorific commonly applied to senior male musicians which can be applied equally easily to first or last names. This man was a disciple of a very significant singer named Balakrishna Ichalkaranjikar. Ichalkaranji is a small city in Maharashtra state, and “kar” is a suffix denoting affiliation. Thus Balakrishna Buva Ichalkaranjikar is “Senior male musician Balakrishna who comes from Ichalkaranji.” He was one of the most important singers to represent the Gwalior sub-genre of khyal singing, and one of the people most responsible for the growth of khyal singing in Maharashtra in the late nineteenth and early twentiety centuries.

Mallikarjun Mansur’s early training was six years long, and was “inside” the Gwalior style, which focused on the clear presentation of relatively short songs, with improvisations that emerged organically from the composed material.

After that, the young singer “jumped ship,” changing his allegiance to the more complex tradition pioneered by the great khyal singer Ustad Alladiya Khan, and learning with the master’s sons, Manji Khan and Bhurji Khan:

He was introduced to Manji Khan…. Mallikarjun had by then sung Gaud Malhar and Adana for HMV. Manji Khan was impressed by the records and tied the red thread of discipleship around Mallikarjun’s wrist.

Practice began at eight every morning and went on until 1.00 p.m. {snip} “Whether it was a straightforward raga like Yaman, or a twin raga like Basanti Kedar, or a complex raga like Khat, the stream of his (the guru’s) singing flowed with astounding power and beauty. And once I began learning from him, my personality underwent a change. I felt there was nothing other than music for me. Here was nectar for a thirsty man.’

But this discipleship lasted for only a year and a half. It came to an abrupt end with Manji Khan’s premature death. Mallikarjun went to his master’s father, the venerable Alladiya Khan, and begged to be vouchsafed more insights into the Jaipur style. The elderly man said he was no longer in a position to devote five hours a day to a disciple and directed him to his second son, Burji Khan.

Mallikarjun found that Burji Khan was a true teacher, in that he understood the disciple’s strengths and shortcomings. Above all he learnt from Burji Khan how to eschew slackness and how to achieve creative independence within the framework of tradition.

H.Y. Sharda Prasad

Characteristics of Alladiya Khan’s “Jaipur-Atrauli” tradition include a wide repertoire of uncommon ragas (perhaps analogous to a jazz musician who chooses obscure material for improvisation rather than rely on the same standards everyone else uses) and an approach to improvisation that builds extraordinarily complex melodic lines using repetition and variation. A common criticism of this style is that it tends to be overly intellectual and “dry.”

As you can hear, Mansur resolved that issue by singing with fervor, passion and joy. Even the most complex melodic structure was handled with a contagious enthusiasm. I have a very poor quality recording of him singing one of the most majestic ragas in the tradition, Raga Darbari Kanada. It is meant to be handled with dignity and majesty, and indeed Mansur presented these aspects with a power that went well beyond what it seemed his tiny frame could encompass. And at the end…the first thing you hear after the final concluding notes — before even the audience’s applause has a chance to begin — is Mansur’s full-throated, roaring laughter.

Here are two of his favorites, ragas Bihari and Paraj:

His one vice was tobacco; he was as enthusiastic about the smoke entering his lungs as he was about the songs coming out of them.

Mallikarjun had always led a simple life. He worshiped music and wanted to share its purity and joy with all his listeners. Worldly success meant little to him. Struck by lung cancer, the end came on Saturday September 12, 1992. In a Doordarshan interview telecast after his demise, he had expressed satisfaction at the vastly growing interest in classical music saying, `In the olden days we had so many veritable colossi in music of the highest calibre, but the audiences were small, exclusive and limited. Today, there are mammoth audiences, but sadly very very few musical giants left.`

Wiki

Eighty-two years old. Not bad for a lifelong smoker. The last time I heard him sing was in 1991; he performed for about forty-five minutes to a small and very enthusiastic audience in Pune. His voice was weaker than it had been a few years before, but his spirit and will were indomitable.

In a a tribute to Mansur published in 1991, the famous Marathi writer P.L. Deshpande recalled:

When (he) turned 60, some of us went to pay our respects to him in Dharwad. When the greetings were over, the tambouras were tuned. He sang Multani, then Shri, LalitaGauri and Naat. The following morning we heard Khat Todi, Shuddh Bilawal and Sarang. It was an uninterrupted cascade of music. One of us asked him, “Isn’t music a lot of hard work?” He shot back, “Hard work? No. Music is nothing but joy. I’m lucky to be a singer.”

And I’m lucky to have heard him.

Thank you for reading and listening. I hope you enjoyed the music.

Mansur is intoxicating. Its like waves which keep on coming to a seashore as infinite repetitions. It enters your heart, and comes out as tears through our eyes.

This piece of Mallikarjun melts my heart. I am listening to it the third time today

This is another article where reference to Mallikarjun’s rendition of Gaud Malhar is mentioned

“We return to maana na kare ri in what is indisputably the greatest performance of Gaud Malhar on record. Mallikarjun Mansur‘s tour de force is manna for the soul. This manner of singing can only come to those in whose bones the daemon of ‘madness’ has taken refuge. This cannot be the handiwork of rational beings.”

I chanced upon this article while googling for Mallikarjun who has recently become my favourite singer. Thanks a ton for this all encompassing article on the musical genius of Mansur, a musician of extreme simplicity and discipline. You are lucky that you could listen to him in person unlike people o my generation. Hope you like the link below:

What is your E-mail contact? (Mine : pgrnair@gmail.com)

Dear Warren:

Some two videos of the maestro which you have linked to in youtube are missing. If you have downloaded them, can you upload them again or could you mail them to me? Please leave me your email id.

Naveen Bharathi

There is something Mansur-like in this article: making very complex things look and sound very easy. Thank you for the words and the music.

He’s one of our favorites around here! We did indeed enjoy the music! Thanks for this insightful article!

The emotion expresses by this so called “Dry” Gharana singer is astounding and is the Hall mark of Greatness !