humor India Personal: hippies sociology Tribhuwan Kapur

by Warren

1 comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

A Few Words About Hippies and India

Anyone who’s spent time in India knows the phenomenon of the hippie. Hippie participation in Indian music started thanks to George Harrison and Ravi Shankar; while many professional Hindustani musicians earn healthy teaching fees from these questing souls, most of them regard “hippies” with a justifiably skeptical eye.

About ten years ago, members of the USENET newsgroup for Indian classical music (rec.music.indian.classical) engaged in a lengthy and vociferous discussion of “hippies in ICM.” As a former hippie and a full-time professional Hindustani musician, I was in a unique position to clarify matters, and I assembled a post which, it was agreed, shed some light on the matter. I thought I’d share it with you, only slightly revised.

The word “hippie” is bandied about indiscriminately by commentators from different parts of the cultural/political spectrum. Please allow me to address a few of the varied nomenclatural issues attendant upon this term, which is rich in emotional and cultural resonances ranging from extremely positive to extremely negative.

First: basic history, with jokes.

“Hip” was originally jazz musicians’ slang dating from the 20s or 30s, with two related connotations. The first was an adjective, translating roughly as “culturally aware.” One who understood the music and the lifestyle of jazz musicians was “hip.” Within the musicians’ community, the term carried strong approbative meaning, and was used generally to mean “knowing,” “appreciating” or “understanding.”

General conversational example:

Q: Have you heard Roy Eldridge’s version of “Let Me Off Uptown”? What a great record!

A: I’m hip!

…that is, yes, I’ve heard it, and yes, it’s a great record.

Second example:

Q: what’s that really hip chord substitution that Sadik Hakim used on the bridge of “I Cover the Waterfront?”

A: He’s using a subV-to-diminished sequence instead of the standard ii-V progression. Yeah, it is really hip!

In this example the word has added connotations of “innovative,” “engagingly novel,” and “giving evidence of exploratory thinking.”

BTW, Sadik Hakim was originally named Argonne Dense Thornton (can you imagine having the word “Dense” for a middle name?), but converted to Islam in the mid-1940s, one of the first African-American jazz musicians to do so.

The second connotation of the word was an antonymic relationship with the adjective “square.” A “square” was one who didn’t understand any part of the musicians’ world, and indeed had no sympathy with it. Squares were the folks who didn’t want their daughters marrying saxophonists, (and, by analogy, they’re the ones in India who don’t want their daughters marrying sitarists). In general, a “square” was somebody driven primarily by economic motivations, somebody for whom possessions, social status and conformity with prevailing norms was the sine qua non of day-to-day life.

The word “hippy” came about as a jazz musicians’ pejorative in the 40s and 50s, denoting a person originating in the square world who had aspirations to hipness…who attempted to speak in jazz jargon, but didn’t quite connect, as in the following example, where the adjective ‘hip’ is used incorrectly in place of the verb ‘dig’:

HIPPY (to jazz musician): Hey man, hip that chick over by the bar.

Jazz musician (going along with it): Yeah, I’m dig!

The “beatniks” emerged from the so-called “beats;” the suffixual ‘nik’ is a Yiddishism, as in the engaging “nogoodnik,” meaning “rascal.” During the fifties, “hippy” was a synonym for “clueless wannabe beatnik.” The term, however, fell into an innocuous desuetude by the early sixties….just in time for its revival (often attributed to Herb Caen of the San Francisco Chronicle) as a descriptor for the young people of that decade who were rebelling against the “square” values exemplified by their parents, World War II veterans who were partaking of the new American prosperity along with the old American hypocrisy.

These new hippies didn’t particularly want to be jazz musicians, and they didn’t particularly want to be black — it was more that they DIDN’T want to be their parents.

With the inevitable passage of time at the rate of twenty-four hours a day, this generation of youth has gotten somewhat older; when Ted Richards’ comic strip “The Forty-Year-Old Hippie” was first published in the early 70s it was hilariously improbable. Now that same hippie is a card-carrying member of AARP and may be eligible for Senior discounts. Most of the time s/he doesn’t smoke pot any more, and most of the time her/his hair is no longer a tangled mass. Hell, some of the time they’re “ex-hippies” with big investment portfolios and George W. Bush stickers on their SUVs. There are some, however, who continue to reject mainstream American values, and more power to them, I say. I’m glad they’re there; they represent the best aspects of “hippiedom” — a willingness to take chances, a deeply felt idealism, an indifference to superficial consumerist trends…all of which I hope I am not alone in regarding as positive attributes!

A number of these 60s hippies got drawn to India and Indian culture; while some of these were enraptured by George Harrison and “all that,” others were looking for various types of spiritual elixir. Thus, by the late 60s, India was subject to an extraordinary new category of tourist, and here is where another and wholly different set of connotations for the word “hippie” enters the picture. These connotations have more in common with the Rush Limbaugh perspective, but the drug-addled gasbag would be unable to articulate them as cogently as the author I’m about to cite.

In a book published sometime in the late 70s, Tribhuwan Kapur strikes a new note in academic research, combining the style of sociological description (sentences in 3rd-person passive voice, ponderous syntax, jargon-laden phrases, etc., etc. ad infinauseum with soft-core pornography (more on THAT in a second; keep yer shirts on, folks). This tome, tantalizingly entitled “Hippies: A Study of Their Drug Habits and Sexual Customs,” appears to be a master’s or doctoral thesis from an Indian university. I found my copy at the block-long used-book sale that runs continually near Churchgate in Bombay; suspecting a fabulous period piece, I snapped it up at a mere Rs. 125.

Kapur’s definition of “hippie” conveys the gist of the prevalent Indian conception of the term.

Allow me:

“PERSONALITY TRAITS PROPOSED AS CHARACTERISTICS OF THE HIPPIE

Given below, as propositions, are properties that hippies might, or might not, have but some of which, as mentioned earlier, are inalienable to them, and in extreme cases, are all found in a single person. It is proposed that a hippie is:i – A person in rebellion against his own culture.

ii – A person in rebellion against each and every culture.

iii – A person who is, and has been, using certain drugs.

iv – A person who is, and has been, using every available kind of drug.

v – A person who has sexual mores and norms overtly apart from the cultural idea of mores and norms regarding sexuality.

vi – A person who has sexual mores and norms that would violate all ideas of ‘normality’ no matter what culture they belonged to.

vii – A person who had a rich/very rich economic-cultural background, or at least a middle-class upbringing with little economic want.

viii – A person, irrespective of background, who discovered within himself an apathy to or violent hatred of affluence.

ix – A person who has negated, and is negating, every form of employment and is against the concept of a boss.

x – A person for whom a job is only a means to carry on with his ‘real’ life which is lodged in the propositions, i to ix.

xi – A person who feels that itinerance is an essential part of life.

xii – A person to whom itinerant travel is life itself, and who perceives that stabilization in terms of living in one place for a stretch of more than three to six months is ‘stagnation.’

xiii – A person to whom ‘freedom’ is the essence of life and to whom all all effort should be garnered around that concept.

xiv – A person who feels freedom is the hippie way of life, i.e. following properties given above is freedom itself..

xv – A person who feels that religion needs to be reinterpreted to become truly religious.

xvi – A person who feels that to be free one must negate one’s own religion especially if one feels that it is false, and carry on one’s quest for freedom with the help of another religion.

xvii – A person who perceives himself as being superior in every way to all human beings not following his way of life.

xviii – A person who feels he is THE most superior being in the world and that all others are not as free as him or her; perceives himself or herself as being ‘wholly enlightened,’ as being ‘saved’ while all the rest are ‘doomed.’

xix – A person who has acquired an indifference to his or her clothes, personal appearance, and physical cleanliness.

xx – A person who sees in his indifference to the body signs of having transcended the flesh.

xxi – A person who is weak, malnourished and suffering from some chronic disease.

xxii – A person who sees in living with disease evidence of a total detachment from the problems of the physical world.The above cover the basic propositions that comprise the basic personality traits commonly found among those that can be classified, hippie. However, as we have noted, not all those who can be so called have all these traits, but there do exist several of the propositions which are necessary, and in themselves sufficient, to categorize a certain type of person as a hippie.” (Kapur, pp. 3-4)

Kapur goes on to offer details of methodology, noting that his research team’s methods of gathering information left them open to false input from their reluctant informants, which

“…led us to feel that the only real way of knowing whether a certain group of hippies was, or was not ‘ripping us off’ with false information was to observe them through a day or so and see the motions they went through. The method used to get valid information during such times was that of non-directed conversation allowing them to ramble, interspersing questions only when one needed clarification on any matter.

Such non-directed conversation helped us participate-observe in many hippie situations and listen to a great deal of hippie conversation ranging across all the concerns that will be tackled in this study. It also helped us cross-check, without really appearing to do so, some of the dubious information that other hippies had given us. We also got to see the kind of places they slept in, the food they ate, who their sexual partners were, and so on.

The chief advantage, then, of this method was that we got to see hippies inside their homes and often witnessed acts that even we, who had come prepared to see and hear all, found bizarre in the extreme; yet it was these very sights — hippies making love in one corner oblivious of the others; a junkie preparing himself a fix, and shooting it in his thigh where a hive of needle marks formed a mini-galaxy; hippies sharing a hashish chillum; eating malnourishing broth for all three meals; living without water — that convinced us that our study was worthwhile, and worth pursuing over the four years it took us to conceive the project and slowly bring it around to a scientific basis, and perform an adequate ethnography.

The disadvantage, in the main, was that often it appeared we were simply wasting our time, for a hippie who has dropped sleeping pills and is awake is hardly capable of talking sense, often simply ‘passing out’ for hours on end. We learnt, too, that some hippies were beyond communication and had had their minds ‘bombed out’ by over-use of one or the other drug. Their case histories could not be had first-hand but only from some of the hippies with whom they were staying and who claimed to be their friends.” (Kapur, pp 11-12)

This must have been one heck of a study, folks. Do you think he got funding from India’s University Grants Commission to send graduate students out into the field to do ‘participant-observation’?

Eventually he gets around to the case histories, and here is where the, er, non-veg bits start creeping in. Antecedent to actual excerpts from the interviews with the hippies (in which their drug habits and sexual customs are outlined in a detail sufficiently vivid that this report must have been pretty titillating to the stolid academics to whom it was putatively directed) are brief descriptive paragraphs:

“CASE FIVE. PROMISCUOUS HETEROSEXUALITY AS PURE HEDONISM.

ULLA, 26, GERMAN.

Ulla is 5’4″, and has pure Aryan features with a creamy complexion, blue eyes, and long light brown hair which comes down to her shoulders. She wears a tight kurta, which accentuates her figure. She wears denims and chappals. Her lips are painted purple and are full, sensuous and moist. She constantly runs her tongue over her lips as she talks about her sexual history.”

(Kapur, pp 81-82)

and, just in case you didn’t get the point:

“CASE TWENTY. SOPORIFICS TO BE IN THE CROWD.

SHERRY, 23, FRENCH.

Sherry is an attractive young woman, with a magnificent figure. She wears harem pants and a gossamer-thin vest through which her pink nipples are clearly visible. She has evenly formed lips and a sensual mouth. She smiles dreamily, and shifts forwards time and again revealing the tops of her creamy breasts. She is of medium height, has blue eyes with dark circles under them. Her skin is creamy, and there isn’t an inch of fat on her slim body. Her hair is bobbed and looks clean. She is barefoot. She speaks in a sensual American-French accent, smiling seductively once in a while.” (Kapur, pp 58-59)

The male interviewees don’t receive the same treatment, even when the interview content was sensational.

“CASE SEVENTEEN. POLY-SEXUALITY AS AN INROAD TO PSYCHIC POWER.

VINCENTE, 30, MEXICAN.

Vincente is 5’6″, hollow-cheeked and bright-eyed, and has matted black hair, is dressed in a saffron robe, and has sandal paste on his forehead; he carries a begging-bowl and a trisul (trident). He has a bag slung around his shoulder and is dark-skinned, and barefoot. He wears three layers of coloured beads around his neck. While talking he generally does not look you in the face, looking over your shoulder or at the floor.” (Kapur, p. 132)

Vincente described a personal history that would have raised Alfred Kinsey’s eyebrows; if you want to read it, you can find a copy of Kapur’s book.

Some of the interviews focus on drug-use habits, but as long as the subject is female, the descriptive style is consistent:

“CASE ELEVEN. SPEED AS CORE OF LIFE ENERGY.

HENRIETTA, 22, POLISH.

Henrietta is 5’7″, and has a pale, unhealthy complexion. Her hair is dirty and knotted; her lips are thin and usually curled in a smirk. Her breasts are unusually large though flabby, and her blue-brown-eyes are animated with hysterical intensity. On her fingers are rings, all synthetic. Shye wears dirty denim jeans with hippie slogans like ‘Make Love Not War’ stitched onto them. She wears rubber slippers. She admits that she is ‘hyped on speed-balls’ even before the ethnographer has a chance to go beyond naming the origin of his…introduction…” (Kapur, p. 45)

Further excerpts will be left to the imaginations of those readers meshugeneh enough to have gotten this far.

In any case, Kapur’s interviews paint a pretty grisly picture of the (mostly Western) young people who overturned conventional tourism during those turbulent decades. Some of them can still be found, mostly in Goa and (to my perennial distress) in my Indian second home of Pune, where the Osho (Rajneesh) ashram has built a thriving spiritual cottage industry, a sort of Club Med-itation.

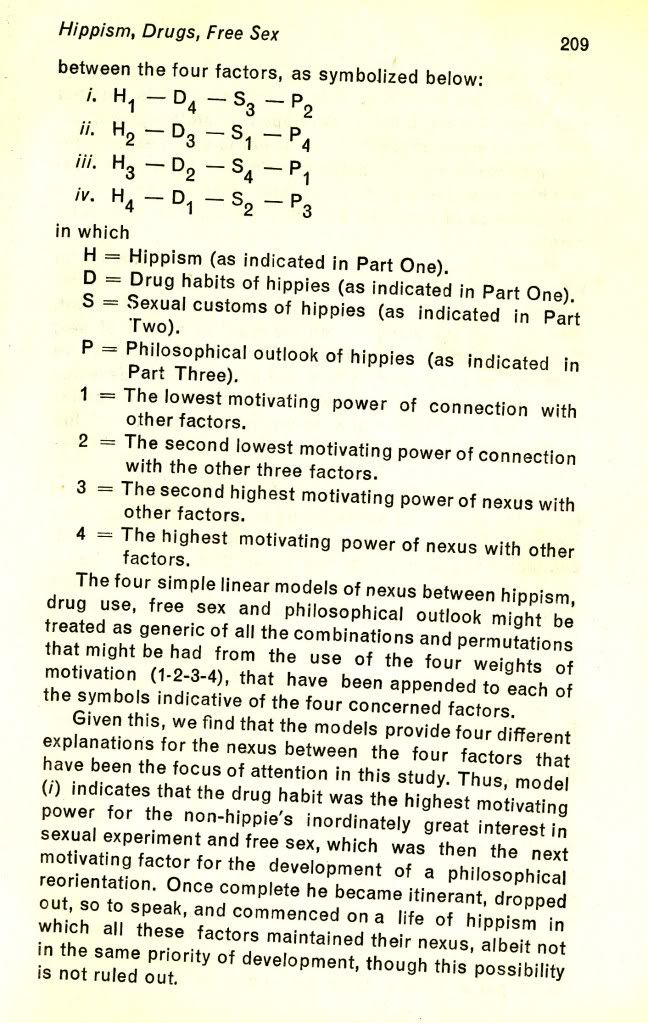

He concludes with a prismatic fusillade of sociological analysis:

I am afraid that the allure of this subject has led me astray. Let me try to regain my footing, as it were.

While “hippie” is jam-packed with connotations for Americans and westerners generally, quite a few of them are positive or at least neutral. I am not offended when old friends refer to me in my hearing as a “hippie,” because I recognize that they are referring to the few tattered vestiges of my idealism that flutter bravely in the breeze of the new millennium, or to the simple fact that I’ve stuck to my chosen life path despite its (all-too-evident, alas) lack of substantial remuneration. I was in fact too young to be a hippie; I was born in the late 50s and became conscious in the late 60s. But I had long hair and all the accoutrements of hippiedom during my callow youth in the 70s, and I had a pretty good and pretty interesting youth, too, for a Johnnie-come-lately hippie manque.

The subsequent years have been rather cruel to my hair, and what’s left of it hangs well above my ears, but my university students appear to see through my lack of locks to the unreconstructed individual beneath — one undergraduate told me he had joined my course because a friend had told him I was a “totally rad hippie professor.”

Ahem.

While negative connotations for “hippie” abound in the west, they are of two basic varieties: either indicating “hopelessly-out-of-it-old- fart-with-bald-spot-and-pony-tail-still-trying-to-get-people-to-join- the-food-cooperative” and variations on the above (by the way, food co-ops are a great way to save money)…or indicating squishy New Age spiritualism, most probably coupled with cluelessness so severe as to be pathological. Both of these general applications for the term ‘hippie’ can be found in the fatuous utterances of Rush Limbaugh and his adherents. Neither connotation is particularly damning, referring more to personal naivete or gullibility than to moral bankruptcy of a more extreme sort, and as I said above, there are a sufficient number of positive connotations that the term is not inherently one of abuse.

But the Indian connotation of “hippie” is quite different. Just as the demographic slice of Indians in the US is highly skewed in the direction of extreme intelligence, ambition, expressive abilities and a host of similar attributes (because in general, the people who finished at the bottom of their college classes never got scholarships, job offers or other opportunities to travel, work and reside abroad) — those “hippies” who made up Kapur’s demographic were the ones who combined spiritual aspirations, gullibility and family money in a manner which, as it were, epitomized the most extreme aspects of the zeitgeist, and which, even now, can be seen in India (outraging the sensibilities of most Indians, except for folks who make their money selling goods, services or advice to the you-know-who).

To Westerners who, like myself, have tried to live within the context of Indian culture in a respectful way, this can be quite galling, when it’s not humorous. When visiting my in-laws in the Bombay suburb of Thane about fifteen years ago, I took a walk through the neighborhood. A little old man with rumpled hair and a raincoat came up to me and said (in a tone of voice that suggested he was equally ready to retail me feelthy French postcards or hot wristwatches, kept beneath his grubby mackintosh) “you want meditation, sir? I have very good meditation!” Any Western traveller in India will tell you similar tales.

The point of this entire exercise, the writing of which has abstracted me from my multifarious domestic exigencies, is that the term “hippie” is so laden with contradictory meanings and emotional resonances that its use in a conversation is likely to be misinterpreted. I hope that in my own small way I have provided both a guide for those who, misinterpreting in one direction or another, find themselves baffled by unexpected rebuke or opprobrium — and a sort of operational glossary which casual readers may use to orient themselves.

And by the way…

Man, really want to know how can you be that smart, lol…great read, thanks.