Indian music music: India photoblogging travelogue

by Warren

14 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Musical Journeys in India: An Audio Travelogue

I must have been eight or nine when my Uncle Russell began taking me, once a month, to a lecture series at the university where he taught; each month a different world traveler would do a grownup version of show & tell. Slides, movies, anecdotes, facts. Exciting? I loved those outings, and I wish I remember more. But they certainly made their impression: as a boy, I knew that I wanted to travel, to see at least a few of those places first hand. Uncle Russ’ career as a management consultant for the Ford Foundation had taken him and his family to live in places far from the Boston suburbs where I grew up. One of those places was Hyderabad, India, and the souvenirs he and my aunt brought back from their years there were my first introduction to Indian culture.

I was seventeen when I encountered Indian music, and from the moment my ears opened to the sound of Hindustani ragas, I knew that this was something I had to do. Over the years that followed, I collected LPs and cassettes of Indian music with zeal; by the time I actually went to India, I had steeped myself obsessively in its classical and vernacular music. Now, thirty years later, I’ve got some show & tell of my own.

I was twenty-seven when I first went to India. I’d been studying Indian classical music with a teacher in Boston for a little more than eight years by that time, so the only thing that surprised my friends was that it had taken me so long to make the leap.

In 1985 I was awarded a substantial fellowship from the Council for International Exchange of Scholars to carry out research in my artistic discipline (Hindustani vocal music of the khyal genre). Nice; very nice indeed. I tidied up as much of my life stateside as I could and flew into New Delhi in September of 1985. A few days later I traveled to the place that has become my second home, the city of Pune in the state of Maharashtra.

Since then, I’ve been back and forth countless times, both for short visits (my wife’s family lives in Pune, so we go as often as we can) and sometimes for longer stays to continue my study and research. And over the years I’ve documented a lot of interesting sights and sounds: enough for many articles. So consider this the first of a series, with more to come.

This piece is in five parts:

Ganapati in Pune: a look and listen to the city’s biggest festival;

Yavatmal District: two different performances from a trip to a rural area in Central India;

One City, Two Musics: two very different musical events a few hundred yards apart, one July in Pune;

Kashmir: “If there is paradise on Earth, it is here, it is here!”;

In Memoriam: Pandit Shreeram G. Devasthali, 1935-2002.

We’ll begin with my adopted hometown of Pune, (formerly Poona), currently the eighth-biggest city in India.

===================================================================

……..G A N A P A T I…I N…P U N E…………..

When I checked into Pune’s Hotel Amir in September of 1985, I had no idea that I’d landed in the middle of the city’s largest festival; I assumed that rickshaw drivers always careened terrifyingly over the sidewalks and that there were drum groups on every corner. It wasn’t until the following year that I was able to venture into the wonderful madness of Pune’s Ganesh Chaturthi festival, and it was easily a decade later that I learned this riotous celebration actually had its origins relatively recently, in the Indian nationalist movement of the late nineteenth century:

In 1893, Lokmanya Tilak, an Indian nationalist, social reformer and freedom fighter reshaped the annual Ganesh festival from private family celebrations into a grand public event. [1] It is interesting to note that the festival was not celebrated in a public manner until this time but was a family affair among Hindus, who used to celebrate it in a traditional manner.

Tilak visualized the cultural importance of this deity and popularised Ganesha Chaturthi as a National Festival “to bridge the gap between the Brahmins and the non-Brahmins and find an appropriate context in which to build a new grassroots unity between them” in his nationalistic strivings against the British in Maharashtra.[2][3]

[snip]

Tilak was the first to install large public images of Ganesha in pavilions, and he established the practice of submerging all the public images on the tenth day[6]. The festival facilitated community participation & involvement in the form of learned discourses, dance dramas, poetry recital, musical concerts, debates, etc. It served as a meeting ground for common people of all castes and communities, in a time when social & political gatherings were forbidden by the British Rule to exercise control over the population.

At the time, I knew little or nothing of this. I was in Pune to study Hindustani classical singing, and that was the force that directed my days and nights (practice during the days, go to concerts at night). We’ll touch on that enormous musical tradition later; for now, let’s party!

…link…

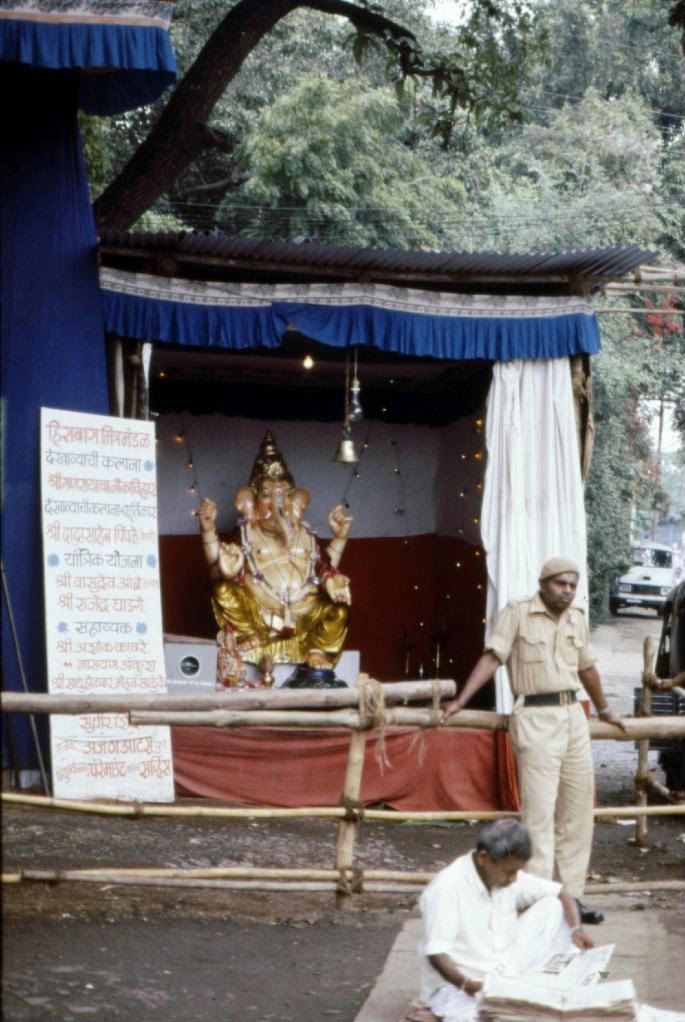

Since 1894, Pune has celebrated Ganesh Chaturthi as a ten-day long festival, in which most neighborhoods put up a pandal (tent) with an idol of Ganesha, often amidst a religious setting, complete with decorative lights and festive music. This festival culminates with a parade of Ganesh idols from across the city carried to the local rivers to be immersed (Ganesh visarjan). The Kasba Ganapati, as the presiding deity of the city, is the first in this parade. The idea of a public celebration was initiated by Lokmanya Tilak in Pune, and has since spread to many other cities, particularly Mumbai, which has a massive parade every year.

…

Ganapati in Pune is no half-way thing! Brass bands, drumming ensembles, student and professional groups — all take part in the great procession that begins on the final day.

Hundreds of plaster statues of Ganesh are taken to the river from the central market in a parade that dwarfs anything I’ve ever experienced. The total distance? Maybe a mile. Total time of parade? Well, it got underway at around noon on September 17, 1986, and it was still going strong at three AM. We’ll start with some images I took during the day, and then I’ll share some of the music and madness of the Ganapati festival’s finale.

just to give an idea of the crowd density…

Often community groups participating in the procession will have their own sound systems, which amplify prerecorded music to deafening levels.

Brass bands frequently have their own keyboard section, which travels in an elaborate chariot with an onboard sound system turned up to Spinal Tap levels; the brass players then overblow drastically to compete. It is an experience of volume that is not easily replicated in America’s very pale parade culture.

This thing was the loudest musical instrument I have ever heard in my life. Look carefully: it’s a solid disc of brass about a foot in diameter. It was heavy enough that two people were required to carry it, suspended on a crossbar. A third man walked alongside, striking it rhythmically.

With a hammer.

A hammer.

For several minutes after this particular group passed, nothing was audible. All auditory nerve signals had been blocked; the entire crowd was completely deafened.

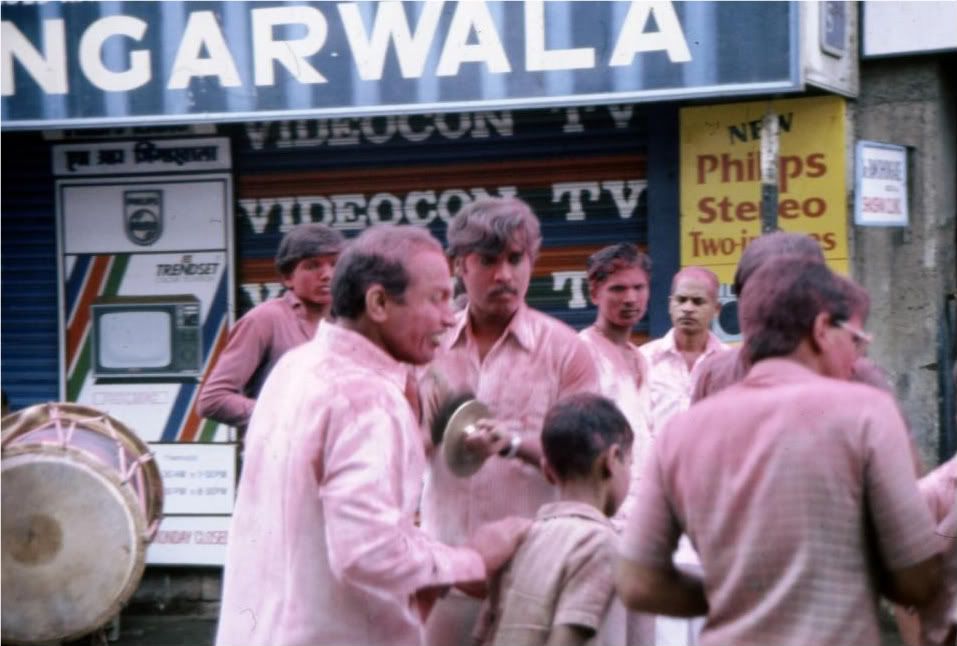

The drumming ensembles include the big cylinder drum, the bright-sounding tasha, and a great many cymbals all clashing together.

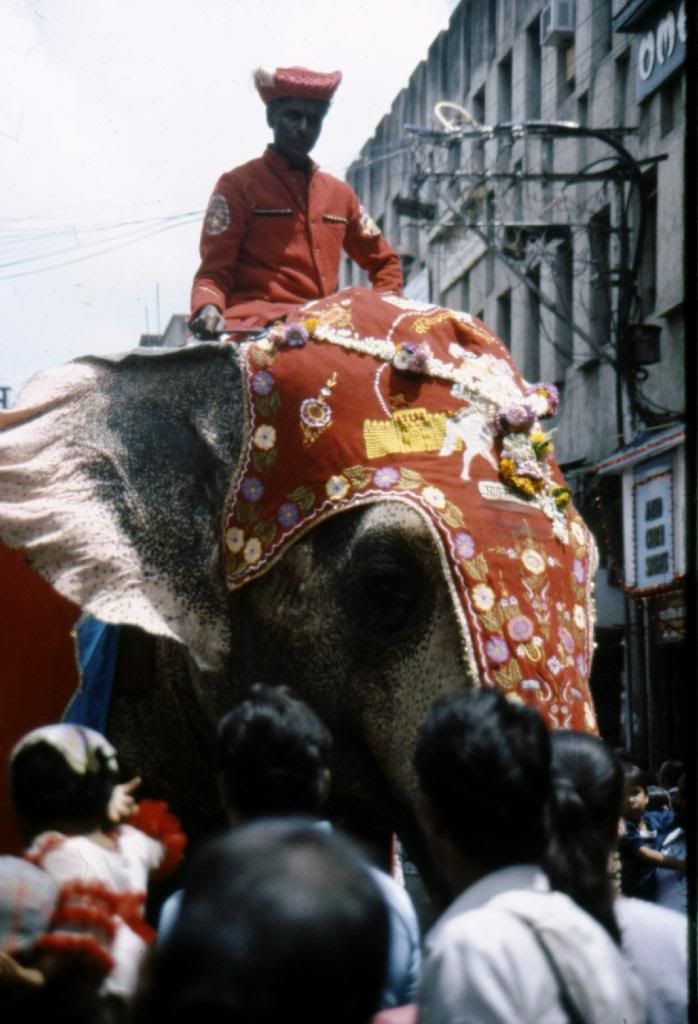

It’s not a parade unless you have at least one elephant.

While the majority of the participants are male, it has become more and more common for women’s organizations and girls’ schools to participate. An all-girl drumming ensemble…rocking out. I love their faces!

I stood and watched for a long time — I couldn’t do anything else, of course, because there were so many people on the sidewalks that I couldn’t move. Groups of young people held hands tightly, forming long “snakes,” and ran through the crowd at breakneck speed in order to get from place to place, yelling warnings to the onlookers. Those of us who were operating solo had to struggle to move more than a few feet.

Later that evening, I tied my glasses on with dental floss, put my camera in a plastic bag, taped my microphone to a stick and put a sock over it, threaded the mic cord through the sleeve of my shirt and connected it to my tape recorder, which I strapped to my body.

Why the elaborate precautions?

I had been warned that Ganapati involved a lot of Red Powder. “Gulal” is an essential part of the festival. During the day it’s possible to walk around without getting hit, but at night? Forget it. Anyone and everyone who was out walking was blasted with fine red dust. I would like to believe it was vegetable in origin, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it was powdered asbestos or something equally innocuous.

Gulal, ready for atmospheric distribution.

Here’s a drum group that got an early start on the red powder phase of the festivities.

By that time, the celebratory crowds have been raising a ruckus for quite a while. Some have been drinking; some have been taking bhang; some are just exuberant…all are noisy and intense in a way that puts American festivals utterly in the shade. Brass bands and drum groups stationed themselves at any convenient intersection and blasted away, regardless of whether there were other musicians within earshot. Walking from corner to corner was a a polyrhythmic, schizophonic experience.

It sounded just like it looks in this photograph. What more can I say?

When I say it was dusty, people don’t really get what I mean. This image gives the correct idea.

Needless to say, I got seriously hit by the gulal-throwers. As one of the very few foreigners walking around, I was an easy and obvious target.

Here’s a sample of what it looked and sounded like on September 17, 1986:

I finally ran out of film, tape and energy, and went home around 3 am. Early afternoon of the next day found me awakening with the Mother of All Sore Throats. When I went to my doctor, he said, “You went out into the festival, didn’t you?” Yup.

===================================================================

……..Y A V A T M A L…D I S T R I C T…………..

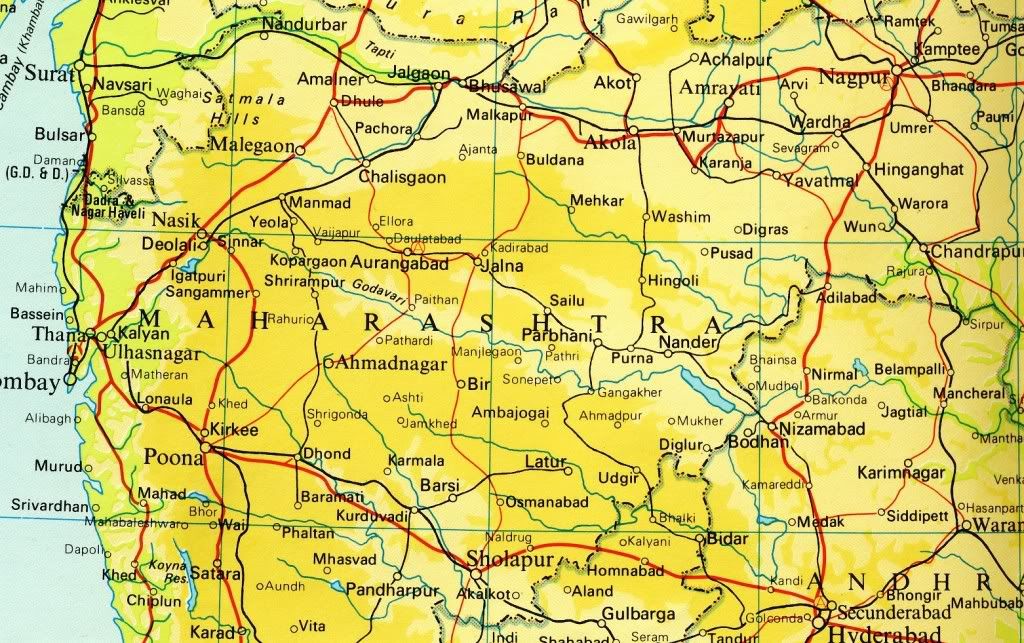

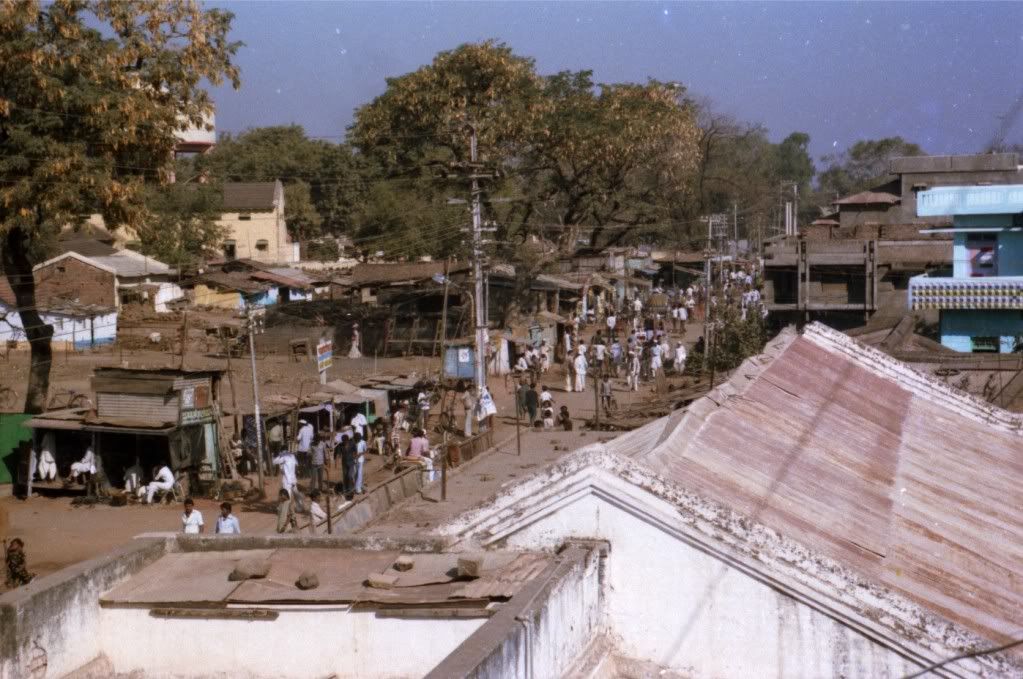

Around the end of 1985, my mother flew over to visit, and we did some traveling, including one of the most improbable destinations imaginable for Western tourists: a small town in Maharashtra’s Yavatmal District, a cotton-farming area where some of my Pune friends had an ancestral home. We were invited to be part of a huge gathering, joining the members of an extended family as they had a yearly reunion in an elaborate compound with multiple individual houses and common spaces. We flew from Bombay (now called Mumbai) to Nagpur, spent the night there and took a 5-hour ride on a State Transport bus that brought us to Warora town, where we were met by a driver with a rickety jeep and driven to our destination, the town of Wani. You can find this area on the right side of the map below; Wani is called “Wun.”

In subsequent conversations with sophisticated urbanites in Pune and Mumbai, I realized that “Yavatmal” is a synecdoche for “way the hell out in the boondocks.” Someone from Yavatmal is presumed to be a country bumpkin.

I will never forget the last two hours of the bus ride. We shared space on the hard bench seat with a village woman who had brought along a goat, which remained standing in the aisle. As we approached our destination, traffic slowed, finally coming to a dead standstill. We were in a traffic jam…of bullock carts, each piled 8-10 feet high with harvested cotton. The air was thick with cotton dust. The sun was merciless, the temperature probably in the mid-nineties with no moisture to be felt anywhere. It was the day after Christmas.

There’s not all that much to see in a cotton-farming town in central India. Cotton. More cotton. Cotton farmers. Dusty streets. We took a ride on a bullock cart (billed as an “authentic Indian experience” by the young man who guided us) and rode on a local bus to visit the family’s cotton plantation.

Knowing of my passion for music, our hosts had arranged for some of their field workers to perform, and I was astonished to see a group of frame drums and flutes accompany a lone male dancer with a massive load of ankle bells. They called it “Dhula Nautch” (“Nautch” means “dance”), and I have never heard any other Indian folk music that sounded remotely similar; in many respects it struck me as closer to the interlocked polyrhythms of African flute/drum ensembles.

After I published this piece on Daily Kos (as part of the Daily Kos Travel Board series), I received an email from a woman who had grown up in Yavatmal district. She told me that her aunt lived in Wani and knew something about “Dhula Nautch,” so I requested that the next time she spoke to her relative, she try to find out more. Here’s what she emailed me a few weeks later:

…I spoke to my mother and my aunt from Wani. According to both of them, dhula naach is performed in the month of March/April five days after the Holi Poornima (full moon day). On the internet you will find information on Holi Poornima. It is celebrated in different ways in North India and Maharashtra. In the Wani area, there is a large population of tribal people and their customs and rituals tend to be slightly different from the rest of the locals. The farmers who were performing for you were most probably enacting the dance that they perform on the panchmi (fifth) day following the full moon or Holi. The Dhul (dust) referred in the title is ash of the bon fire that is lit on the Holi day. The ash is sprayed on people almost in the same manner as gulal during the Ganpati festival. Apparently, the people have different types/forms of dance for different months or occasion. The music recorded by you (according to my mother) sounds euphoric. It is the kind of music played in the months of February/ March when the farmers have harvested good crops.

I have seen these people perform with similar instruments in July/ August for rains. I don’t have a recording but the melody in those cases is definitely more melancholy and the words in the songs convey a message of plea for water to the rain gods.

Not much to do or see in Wani.

As we returned on the local bus, a group of musicians got on, carrying a harmonium and a set of tabla. Irshad, our guide (and the third son of one of our hosts) negotiated with them, and a day later, they came to “Razzak Manzil,” the family compound in Wani, where I recorded eleven devotional pieces in the Marathi language, a type of song generically called Abhang or Abhanga.

Baban Keshav Thakre and the rest of his troup performed a mix of older traditional songs and items they had learned from commercial recordings by famous contemporary singers, including big names in Indian film music like Lata Mangeshkar and big names in Hindustani classical music, like Pt. Bhimsen Joshi.

Here is their version of a devotional song based loosely on one of the popular Hindustani ragas:

And here is one of the all-time most popular items in the Abhang canon, “Pandari Niwas,” which was made popular by the great classical singer Bhimsen Joshi. Thakre and his partners had certainly learned their version from Joshi’s commercial recording, which was extremely popular throughout Maharashtra. These songs all praise a particular form of Krishna:

“Vithoba”, “Pāndurang”, and “Pandharināth” are the popular alternate names of the deity, Viththal, who is regarded in Hinduism as a God form of Lord Krishna, who, in turn, is considered as an incarnation of Lord Vishnu.

link

===================================================================

…….O N E…C I T Y, T W O…M U S I C S……..

One evening in July 1986, I went out with plans to go to two separate concerts; two musical events about as different as they could be. The first? Pune’s number one rock band, “The Strangers,” were playing in the auditorium of Fergusson College, just a short walk from my apartment. A huge audience of college students was in attendance as the band did their set of covers (Clapton, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, etc.). I knew some of the members of the band; as a Western musician in an Indian city I’d become a resource and friend. They played well; Milind Mulick was an excellent lead guitarist (incidentally, he is a watercolorist of astonishing talent whose work has been exhibited internationally).

Milind and Nico, of the Strangers.

It was an interesting show for several reasons. First was that I hadn’t been to an actual rock concert since high school, so I felt more like an elderly anthropologist than I’d anticipated. Second was that it was the only rock concert I’d ever been to where the audience was gender-segregated: a big barricade of chairs and desks split the room, with college-age girls on one side, college-age boys on the other.

There was a fair amount of checking out the other side going on.

The last (but hardly least) reason it was an interesting concert was that the opening act was led by a superbly musical guitarist/vocalist I’d fallen in love with; we would marry two years later in a traditional Hindu ceremony with her parents’ approval, and twenty-three years down the line, Vijaya and I are still happily together.

My own true love, rocking out!

But I digress.

After the rock concert ended and I said goodnight to my sweetheart, I walked a few hundred yards to the main road, and another few hundred yards to the entrance of a popular restaurant, the Hotel Poonam (in India, restaurants are often called “Hotels.”). The Poonam had a large upstairs room which they rented out for private functions, and that evening I had been invited to attend a private concert given by the magisterial Hindustani singer Bhimsen Joshi. The daughter of one of his old friends was getting married, and he had agreed to perform as a wedding present.

I arrived as he was getting set up: tuning the droning tambouras, supervising the tuning of the tabla drums, and trading quips with his accompanists. He beckoned me to set up my tape-recorder at the front. I had received my Fellowship in part because Bhimsen Joshi had agreed to teach me music; while he was temperamentally uninterested in teaching, he was very generous in allowing me to record his concerts.

Hindustani classical concerts go on for 3-4 hours, so it doesn’t make sense to include much of his performance in this piece. One item, however, is relevant. The video/slideshow in 2 parts which follows is Bhimsen’s concert-length, classically embellished, virtuoso handling of “Pandari Niwas,” the same abhang presented by Baban Keshav Thakre in that little room in Wani, Yavatmal District. Remember, of course, that those vernacular musicians had learned the song from Bhimsen’s recording…which in turn was an adaptation and revamping of traditional lyrics and melodic material to begin with.

The total performance is 19 minutes long, so it’s in 2 parts. As you listen, enjoy the melodic variations, which incorporate tones from outside the original scale. The classical performance context allows for the rendition of lighter material: folk songs, devotional songs and the like — all categorized generically as “light classical music.” Well, this may be “light,” but Bhimsenji’s ornamentations and improvisations make this an extraordinary demonstration of musical creativity. Listen and enjoy:

Bhimsen Joshi: Pandari Niwas, July 26, 1986 — parts 1 & 2

===================================================================

…………..K A S H M I R…………..

Earlier in 1986, a friend and I traveled through multiple destinations in North India. One of the places I’d always wanted to visit was Kashmir, which had not yet become a problematic destination for Western tourists. I had been bewitched by Kashmiri music since first hearing David Lewiston‘s wonderful recordings on the Nonesuch Explorer label in the mid-1970s, and I knew that I wanted to see and hear Kashmir for myself.

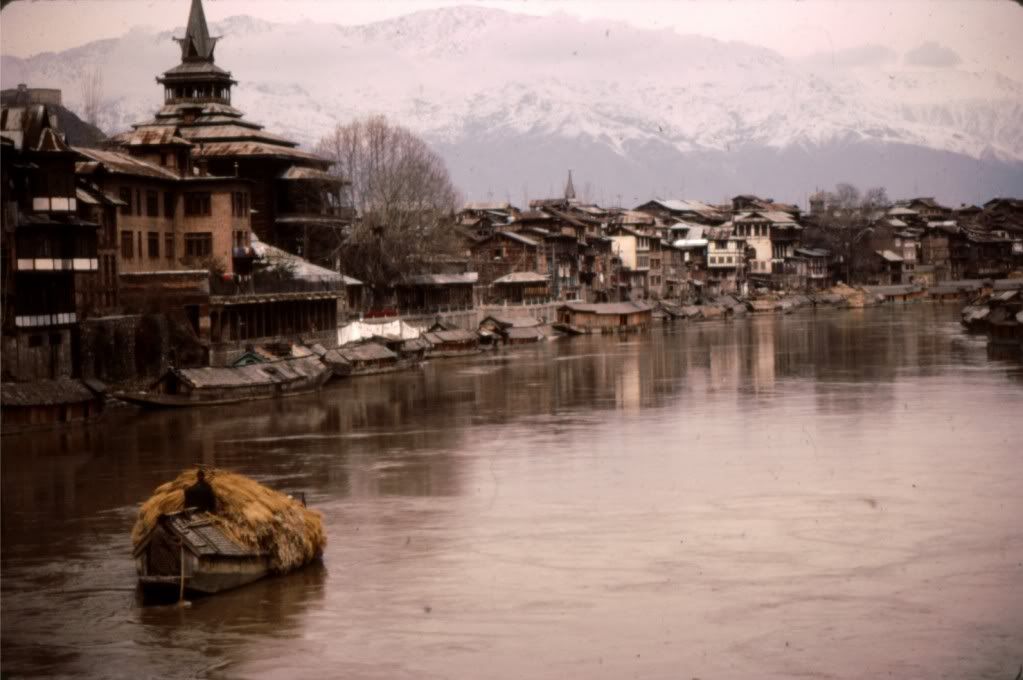

Cradled in the lap of majestic mountains of the Himalayas, Kashmir is the most beautiful place on earth. On visiting the Valley of Kashmir, Jehangir, one of the Mughal emperors, is said to have exclaimed: “If there is paradise anywhere on earth, it is here, it is here, it is here.”

Link

As schedules would have it, we wound up in Kashmir in March, which was a little early for tourist season. The flowers weren’t really blossoming in full force, and the city of Srinagar was just waking up from the winter. But that was okay; I didn’t really care about going trekking in the mountains. I love cities, and Srinagar was wonderful.

Kashmiris commonly wear pherans, comfortable wool poncho/capes. Note the bulge under the woman’s garment: she’s not misshapenly pregnant, she’s carrying a kangri, a small charcoal brazier filled with glowing coals and hanging from a small harness. On cold days it’s not uncommon for people to wear several of these portable heating units.

The river Jhelum runs through the middle of Srinagar; heavily laden boats move up and down. While the tourist houseboats are almost all floating in the Dal lake, there are many residential houseboats moored on the banks of the river.

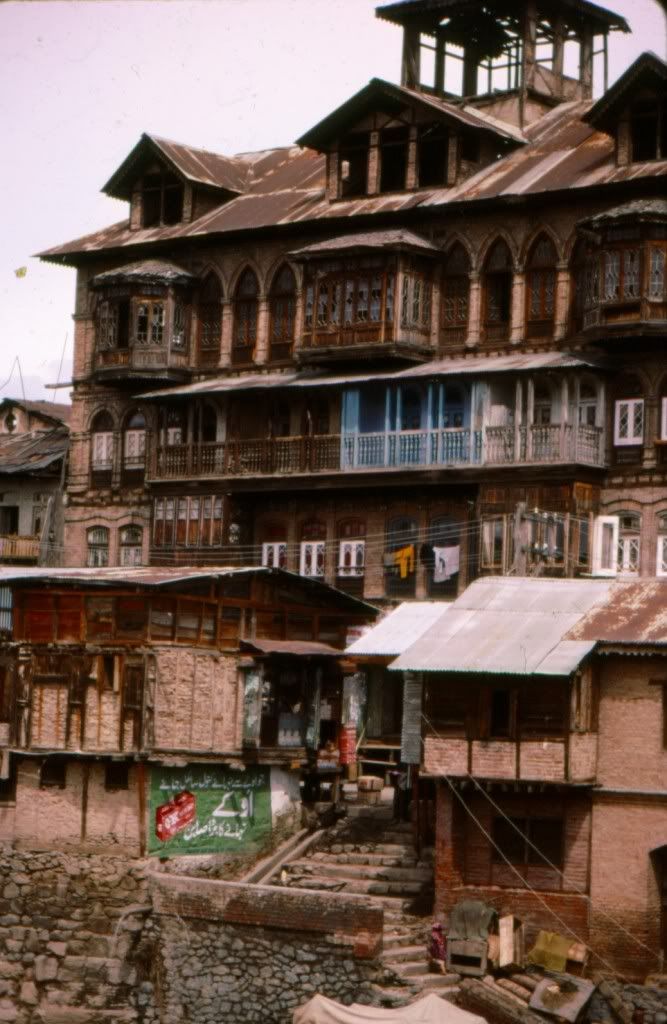

I greatly enjoyed the buildings that lined the river. Multi-story residential constructions, they all seemed to have grown up accretively, one or two rooms at a time.

If you’re not trekking, a lot of what you do when you’re a tourist in Kashmir is laze around in a boat on the Dal lake. Vendors come up to you and sell you everything imaginable from their boats: t-shirts, incense, antiques, flowers… Floating on the water, looking up at the awe-inspiring mountains. It just doesn’t get any better than that.

Another popular tourist attraction was the “floating bazaar.” One morning a week (for some reason I recall it as a Wednesday, although I have no reason to trust myself after all these years) there is a sort of “farmer’s market” where people sell vegetables from their boats, haggling, joking, yelling, calling out prices…while a few hardy tourists watch from the outskirts. It was pretty cold that morning and we were the only tourists present, which was excellent; being ignored is among the greatest pleasures of travel.

But enough with the pretty pictures. Let’s go check out some music, shall we?

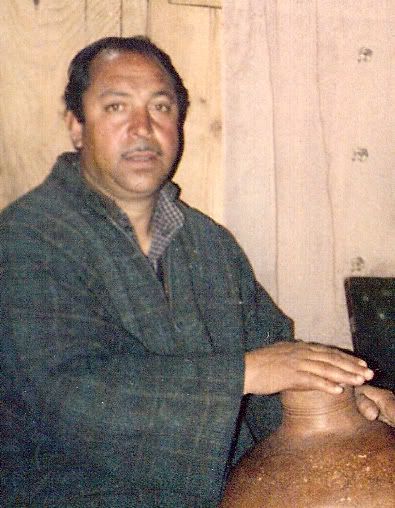

I asked the owner of the houseboat where we were staying to find me music and musicians. He was a trifle taken aback; most tourists are happy enough to hear Kashmiri music in their hotels, but don’t go actively seeking it. But tourism-based economies are all about supplying what the customers want, and a day later he told me that a session had been arranged. A guide came and got us in a cycle-rickshaw, and we rode to the banks of the Jhelum and walked down a small set of steps to a landing, where we boarded the houseboat of Ghulam Mohammed Ahangir, one of the three musicians who had agreed to perform for us. He seemed to be the musical director of the trio, dividing his time between singing, playing a small reed harmonium and providing rhythmic accompaniment on the nuht, an earthenware pot played by slapping and tapping across the sides and opening.

G.M. Ahangir, playing the nuht.

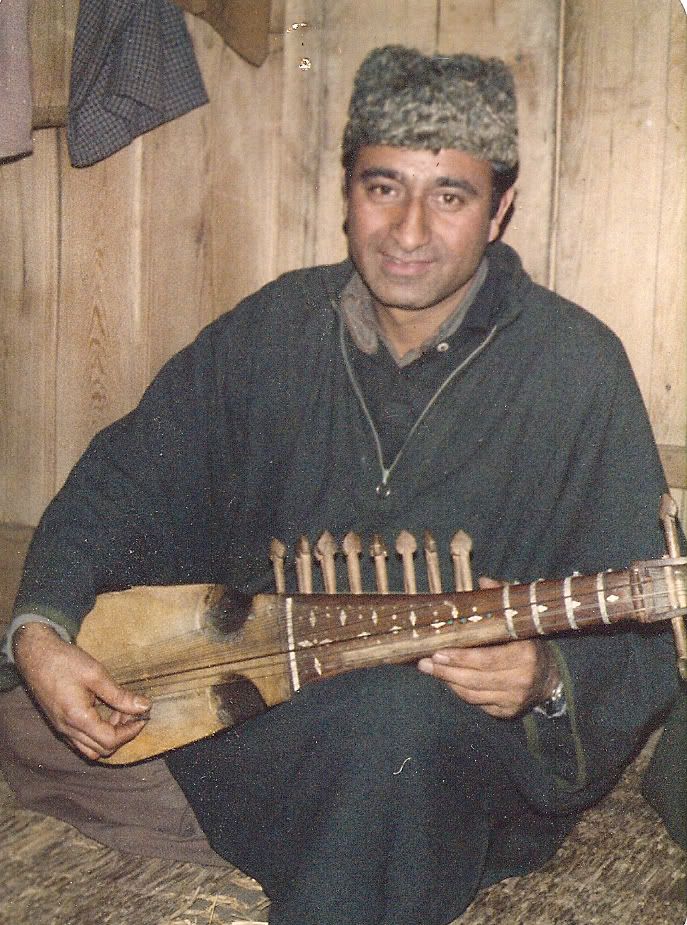

An instrument that I’d always loved is the Kashmiri Rabab, and I was delighted to meet Moi-ud-din Bhat, the rababiya for the evening. The Rabab is a plucked stringed instrument with a skin head, which gives it the projection and bright tone of a banjo. There are a few frets made of gut, tied on at the base of the neck. You’ll see two small semi-circular notches along the body of the instrument; these are reminders of the rabab‘s past as a vertically played fiddle in Arabic and Persian music. As the instrument traveled into India through Afghanistan, it lost the bow somewhere in the Hindu Kush and began to be played with a plectrum. In Indian classical music, the beautiful sarod is a direct descendant of the rabab.

Moi-ud-din Bhat, playing the Kashmiri Rabab.

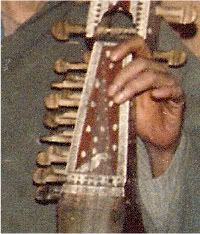

The third member of the trio was Abdul Aziz Parvez, who specialized in the Kashmiri Sarangi, a bowed instrument with a bright, resonant tone that belies its small size. The sarangi is common throughout North India; there are many folk versions as well as the “classical” sarangi found in Hindustani concert performances. The sarangi is played by touching the strings sideways with the cuticle; there is never any downward pressure exerted by the player’s left hand.

A closeup of Abdul Aziz Parvez’ left hand.

Abdul Aziz Parvez, playing the sarangi.

I recorded almost 90 minutes of music that evening, and the tape that resulted has continued to be a personal favorite over the ensuing decades. The musicians began with a medley of traditional Kashmiri melodies. The tunes they strung together had no titles; Ahangir noodled a bit on the harmonium, settled on a line and began playing it over and over until everybody joined in. They kept it up until the melody began to lose its power, at which point they all took a breath and started a new one. This piece was almost twenty minutes long, and allowed them to get their ears and instruments limbered up and synchronized. After that they presented some songs in the Kashmiri language, some shorter instrumental pieces, and a piece of Soofiyana Qalam (Sufiana Kalam), the Kashmiri version of traditional North Indian classical music.

Note: The videos combine the music I recorded with the photographs I took; I’ve included three in the body of this piece, but if you want to listen further, just investigate the “related videos.”

Here is a trio: rabab, sarangi and nuht:

Here’s a traditional Kashmiri song:

And here is some Soofiana Qalam:

===================================================================

……..I N…M E M O R I A M………..

It was in April of 1986 that I met the man who would become my true teacher of Hindustani music. While I loved (and still love) Bhimsen Joshi’s music, it was increasingly clear that he was not going to be the teacher I needed. A series of connections brought me to the home of S. G. Devasthali, in Pune’s Sahakar Nagar neighborhood. A heavyset man with the beard of an ancient sage and the demeanor of a take-no-nonsense high school teacher, he asked me about my experiences learning music thus far….and when he heard how little I’d received from the Great Master, he exploded angrily, “You have been betrayed! To have come so far and received so little!”

He then said, “I will teach you. In our tradition, we believe that you cannot attain moksha (liberation) until you have taught someone else everything you know.” He told me to come on Thursday, two days hence, and gave me directions to the children’s educational institute where he had a second job; his first was as a Hindi teacher at Pune’s Loyola School for Boys (and if there are any graduates of Loyola reading this, you are welcome to share your memories of Mr. Devasthali in the comments).

I arrived at 7 PM, right on time, and he directed me to a dusty room with a dusty rug, a dusty window and a dusty tamboura in the corner. “Tune the tamboura,” he said, “and I’ll come in just a minute.” And shortly thereafter he walked in, sat down, and began singing. Back and forth we sang; I struggled to duplicate his phrases. When I got one right he rewarded me with a megawatt smile before raising the bar a bit with a longer or more intricate passage.

A sound interrupted us. We looked up. It was his daughter, standing in the doorway. “It’s eleven o’clock,” she said in Marathi, “your dinner is cold.” We had been singing together for four hours. He got up and bade me goodnight, and said, “come tomorrow at the same time.”

And that was the day my life changed. Every day after that I had a lesson, lasting anywhere from three to five hours. When he missed a day or had to cut it short, Guruji was apologetic. When I offered him money, he refused it angrily (really angrily).

I have been fortunate in my life; I have worked with some of the greatest teachers in many different fields. I will state categorically that I have never experienced greater power in the transfer of knowledge than during those days when I sat with Pt. Devasthali, singing. My fiancee Vijaya joined us soon afterward, and the two of us were immersed in his music for years.

Guruji: Pt. Shreeram G. Devasthali

In 1991 a team from the American Institute of Indian Studies did a short video documentation of me getting a lesson from Pt. Devasthali. Here’s an excerpt. I hope you enjoy it.

Traditional “Taleem” (instruction) in Raga Shri: Pt. Shreeram G. Devasthali to Warren Senders, April 1991.

Thank you for reading, watching and listening this far. If you want to find out more about me and what I do, you can check out my website. An earlier version of the Pune Ganapati story was posted over a decade ago here (it’s pretty good, actually, and there are some music clips that didn’t make into this article). I have a YouTube channel where you can find more music and images.

This piece was originally posted as a diary on daily Kos. Link.

Hi Warren, I’m an Old Loyola Boy.And a product (I know that sounds a little crassly commercial) of ‘Devasthali Sir’. Not one of his “best products” but still very proud to be one. I’ve used the term ‘Devasthali Sir'(a slightly confused Indian modernism!) here though the actually appropriate term ought to be ‘Devasthali Guru ji’. As I found (pretty late) a Guru is not just a Teacher. He/She is a Parent (to the student/Shishya) and even more. That is precisely what he sought to be. And his statement that you’ve quoted above “I will teach you. In our tradition, we believe that you cannot attain moksha (liberation) until you have taught someone else everything you know.” is an explanation for that. When he taught us in school; I’d been exposed to Music at home (not so uncommon in an Indian Bengali ‘Bhadralok’ family) but that is far as that it went. So while I knew that he was knowledgeable in Indian Music; I had just no idea how deep it really went. Later when my own interest in Music got deeper I accidentally got to know how deep his knowledge of Music went. But that was really towards the end of his life and for a number of reasons; including the fact that I never tried to be a formal student of Music kept me away from accessing that part of his Genius. But Thank You; Warren for re-connecting to all that. Including the memory of the Man that I called ‘Sir’ when in fact he was ‘Guru ji’.

Pradeep Chakraverti; Loyola ’71

Hi,

My comment pertains to the old recording you made in India (Maharashtra, district Yavatmal). I discovered the video on youtube, from which I searched out your post on the Daily Kos (http://www.dailykos.com/story/2009/06/28/741879/-A-Musical-Journey-Through-India-DKos-Travel-Board-21#c29). And finally, I discovered your writings here.

In various parts of India, in her folk musical heritage, I have found parts of what I seek in music. Words fail me, and I can’t really describe it. But never have I felt this attraction more strongly than in Dhula Nautch. Some folk music from the Santhal districts in east-central India come close, however.

I would love to talk to you more about such music, but if you do not have the time, could you please tell me more about Dhula Nautch? Or point me to other sources from where I can learn more about it?

I shall be eagerly awaiting your reply.

Sincerely,

Ritwik Banerjee

Thanks good at last the musical journey have started in india, now from this journey they got the talented people

If only more people would read this..

Thank you for the help.

Great Audio info, i’m bookmarking the page for the great content.

Im new here and i enjoy music and movies alot , Hope lots of ppl like me here 🙂

Intresting, this was actually a very great read! thanks

Thank you! I would now go on this blog every day!

Whoa, cool post. I just found your website and am already a fan. =)

In New Guinea pidgin, throwim way leg means to take the first step of a long journey. Musical

After reading this, I will write something in hindi…which just came in my thoughts..

“smritiyaan bikhri aisii, jyuun kaanch pe neer.

Jeevan ka adbhut pahiya bhaiya, kabhi harsh kabhi peer.”

by Musical Journeys in India: An Audio Travelogue « Running Gamak … | danceteacher

[…] See the article here: Musical Journeys in India: An Audio Travelogue « Running Gamak … […]

Devasthali Sir seemed fierce but I remember him to be very soft hearted with us boys in school. I remember trembling with fear when he called me up to the front of the class. He just lightly tapped my cheek and smiled.