Jazz music Personal Politics: genius improvisation

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Charlie Haden Sounds Like A Rain Forest

It was my fifteenth birthday, and my parents knew I was a budding jazz fan. They got me a wondrous thing: a six-lp set billed as The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz. And it was great. I started at the beginning and worked my way through Scott Joplin and Robert Johnson, Jelly Roll Morton, King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Roy Eldridge, Billie Holiday…it was incredible.

And after taking a breath I listened to Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Thelonious Monk (one entire lp side!), Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, Cecil Taylor…

And the last side had three pieces by Ornette Coleman and one by John Coltrane.

I put it on the player. Here’s what I heard:

Ornette Coleman’s Quartet plays “Lonely Woman”

It started with a melancholic strumming, a giant bass sitar, cushioned in cymbal shimmer. What the hell?

I’d never heard anything so lovely.

And that, dear ones, was my introduction to Charlie Haden’s bass playing.

The early Ornette Coleman Quartet, circa 1961.

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

The first few paragraphs of Charlie Haden’s bio, from his website:

Time Magazine has hailed jazz legend Charlie Haden as “one of the most restless, gifted, and intrepid players in all of jazz.” Haden’s career which has spanned more than fifty years has encompassed such genres as free jazz, Portuguese fado and vintage country such as his recent cd Rambling Boy (Decca) not to mention a consistently revolving roster of sidemen and bandleaders that reads like a list from some imaginary jazz hall of fame.

As an original member of the ground-breaking Ornette Coleman Quartet that turned the jazz world on its head the late 1950’s, Haden revolutionized the harmonic concept of bass playing in jazz. “His ability to create serendipitous harmonies by improvising melodic responses to Coleman’s free-form solos (rather than sticking to predetermined harmonies) was both radical and mesmerizing. His virtuosity lies…in an incredible ability to make the double bass ‘sound out’. Haden cultivates the instrument’s gravity as no one else in jazz. He is a master of simplicity which is one of the most difficult things to achieve.” (Author Joachim Berendt in The Jazz Book) Haden played a vital role in this revolutionary new approach, evolving a way of playing that sometimes complemented the soloist and sometimes moved independently. In this respect, as did bassists Jimmy Blanton and Charles Mingus, Haden helped liberate the bassist from a strictly accompanying role to becoming a more direct participant in group improvisation.

And just as important as his historic role in the evolution of jazz bass playing is his sound. No bass player anywhere has as big a sound as Charlie Haden, and his presence on a recording is always unmistakable (and a guarantee of quality — the man has, as far as I can tell, never played on a bad record).

Charlie talks about music. “I want to sound like a rain forest.”

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

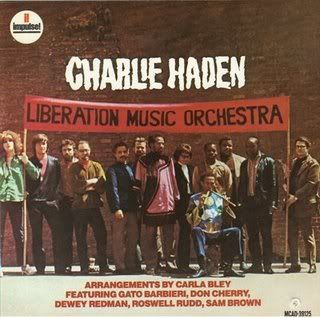

His huge sound is beautifully shown in this clip, where he directs his big band, the Liberation Music Orchestra, in a performance of “Sandino.” Notice, too, the extraordinary accompaniment he plays for Mick Goodrick’s guitar solo — full of drones, strums and pulsing rhythms, and utterly unlike any other bass player.

The Liberation Music Orchestra: “Sandino”

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

As the group’s name suggests, the Liberation Music Orchestra performs a great deal of music with a specifically political slant. In a 2006 interview with Amy Goodman, Charlie describes how the LMO got started:

AMY GOODMAN: You have four records/CDs out with the Liberation Music Orchestra. Can you talk about the first one, how it all began, how you established this orchestra, why its name?

CHARLIE HADEN: I established it from my concerns about what was going on in the world because of the Nixon administration and the war in Vietnam, and I started thinking about, “I’ve gotta do something about this.” And I had some music from the Spanish Civil War that was in my collection, and I started thinking about — maybe I can do — I mean, I had never done this before, you know? And maybe I could do something where I can play some political songs from the Spanish Civil War. I can write a song about my hero Che Guevara and call it “Song for Che.” I can write a piece about the Chicago Democratic Convention in Chicago in 1968, where people were, you know, beaten on the street and jailed.

The first LMO album remains one of the great masterpieces of contemporary jazz — melodic, driving, and fiercely uncompromising in its linking of the struggle against Franco and the struggle against the Vietnam war.

Haden has always been an outspoken political progressive. One of his most controversial moments came on a 1971 tour with Ornette Coleman, when they were playing a festival in Portugal:

CHARLIE HADEN: …I saw on the itinerary before we left that we were playing in Portugal, and I didn’t agree with the government there. It was a kind of a fascist government. They had colonies in Guinea-Bissau, in Angola and Mozambique, and they were systematically wiping out the Black race, you know? And so I called Ornette, and I said, “You know, I don’t want to play in Portugal.” And he said, “Charlie, we’ve already signed the contract. We’ve gotta play. It’s the last country on the concert tour. Figure out — maybe you can do something to protest it, you know?”AMY GOODMAN: The Caetano regime.

CHARLIE HADEN: Yeah. And so, during the tour we were playing one of my songs, “Song for Che,” and I decided that when we played my song, because it was connected to me, because I was the guy that was going to do it, you know, I would dedicate that song to the Black peoples’ liberation movements in Mozambique and Angola and Guinea-Bissau.

(snip)

So I made the dedication, and I wasn’t arrested immediately, but, you know, when I did the dedication there were young people there, students, that were in the cheaper seats in front, and they all started cheering so loud that you couldn’t hear the music. And a lot of police were running around with automatic weapons, and they, right after we finished our set, they stopped down the festival, and they closed down…this big stadium that we were playing in. And we went back to the hotel, and so I was starting to get concerned about what was going to happen.

The next day, we went to the airport, and at the airport, I was trying to get my bass on the plane…there were hundreds and hundreds of people in front of the airlines’ counters. And finally, one of the people from TWA came around the counter and said, “There was a man over there who wanted to interview you, and you have to stay here.” And I said, “I don’t want to be interviewed.” And Ornette came over and said, “What’s going on?” And they say, “They want to interview Mr. Haden, and you guys are going to get on the plane. And he’s staying here.” And Ornette said, “No, we’re not going on the plane. We’re going to stay here with him.” And they said, “No, you’re not. You’re getting on the plane.” They took them by the arms, and they led them on the aircraft. And I stayed there, and they took me down a winding staircase to an interrogation room and started pumping me with questions.

(snip)

It was the political police of Portugal. And so I said, you know, “I’m a United States citizen with a United States passport. I demand to be able to call the embassy.” And the guy who worked for TWA looked at me and smiled and said, “It’s Sunday, Mr. Haden. You can’t call the embassy. You shouldn’t mix politics with music.”

(snip)

…And the next thing I know, I’m in a car, and we’re traveling to a prison. And I’m thrown into a dark room with no lights, and I stay there for I don’t know how long. A long, long time. And finally — I mean, I was traumatized. You know, I thought I’d never get to see my kids. I thought it was over. I didn’t know what they were going to do.

And they finally came and got me from the room and took me up to an interrogation room with really, really bright lights. I couldn’t see anything. And there was one guy who spoke English that started pumping questions at me right and left, and one of the questions, which I was kind of prepared for, because I thought I would kind of try to fool them. He said, “Why did you make this dedication?” And I said, “Well, I’ve been making a dedication at every country we went to. I dedicated something in Germany to the German people. I dedicated something in France.” And he said, “Do you expect us to believe that?” You know, anyway, they brought a statement to me to sign. I refused to sign it, and they started to look —- one guy had a trunch, and …hitting it against his other hand. And as soon as I thought like everything is over with, there was a guy that came down and whispered something in the head policeman’s ear. And all of a sudden he completely changed. He says, “Mr. Haden, you’re going upstairs. Someone from the American embassy is here to retrieve you.”

(snip)

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to the legendary musician, bassist and political activist, Charlie Haden. After this, did it change your thoughts about speaking out? Did it make you radioactive for other jazz musicians? Did musicians support you in what you had done?

CHARLIE HADEN: Most of the musicians that I performed and played and recorded with all supported me. You know, it’s such a struggle for jazz musicians in this country to get their music played and to the people. And in that struggle, they don’t really have time — or, you know, they’re struggling to play their music, and I think that that’s the reason that more musicians don’t speak out politically.

But I started getting worried when the FBI came to my apartment, and they had been watching the house. I saw cars out in front on 97th Street, where we lived, and I knew plain-clothes cars when I saw it, you know. And they finally came up to the door and rang the doorbell, and they said, “We’re FBI. We want to talk to you.” And I said, “Well, why should I let you in?” They said, “Well, we’re asking you if we can come in and talk to you.” So I said, “I don’t have anything to hide. Come in.” So, they asked me, you know, “Why did you do that?” And I told them. I said, “I don’t agree with the policies of the Portuguese government, and that’s why I did that.” And they had a whole dossier on me. I couldn’t believe it.

Anyway, but I thought about it afterwards, and if I had it to do again, I would do it again. And as a result, I think, of what I did, because nobody had ever done that in Portugal, my wife Ruth and I later learned that they put it into the school books of the schools in Portugal, what I did. And there was a revolution in 1974 of the young enlisted officers, and they overthrew Caetano. He fled the country. And I think it was a gentleman named Duarte [Soares] that took over, socialist government. They invited me to come back, and I came back and I played. And there were 40,000 people in this big meadow in Lisbon, and they were all chanting, “Charlie! Charlie! Charlie!” And I had goose bumps all over. It made me feel so good.

And then, my wife Ruth and I were invited back, because I met, while I was there, Carlos Paredes, who was this famous fado player, and I loved his playing, and so I said, “I want to play with you.” He had been arrested under Salazar. And we came back and did a film with him, and they took me back to the stadium where I was arrested in ’71. And they did a little documentary. It was all in Portuguese. And it was really nice to go back.

As part of his long-running project of recording duets with musical colleagues, Charlie and drummer Paul Motian performed a piece titled “For A Free Portugal.” The beginning of the piece uses the tape of him dedicating “Song For Che” to “the black people’s liberation movements” — onstage in Portugal. You can hear the crowd’s reaction.

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Although Haden has always been associated with jazz’ avant-gardists, he has deep sympathy for the entire stream of jazz tradition. On this recording, he accompanies the New Orleans jazz masters Henry “Red” Allen and Pee Wee Russell with such authority that Red Allen gave him the ultimate accolade: “Charlie Haden’s a stompin’ bass player!”

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

In the 1970s and early 1980s, Haden performed often with Old and New Dreams, a quartet built around Ornette Coleman’s concepts, featuring four musicians who’d learned from the eccentric saxophonist and composer. Don Cherry (trumpet, piano), Dewey Redman (tenor sax, musette), Charlie Haden (bass), and Ed Blackwell (drums) made some of the finest and most engaging free music ever recorded. I heard this band several times and will never forget the effect of Haden’s incredible beat in synergy with Blackwell’s percussive tapestry.

The Old And New Dreams Band plays Ornette Coleman’s “Happy House.”

This band gave a lecture-demonstration at Harvard University in 1980, where they discussed their musical approach and the influence of Ornette Coleman. I was in the audience, and several years ago I transcribed the tape. Here’s Charlie, talking about his early experience with Ornette Coleman:

Don Cherry: Charlie! What is the Harmolodic Concept?

Charlie Haden: (waits for audience laughter to die down)…Ornette asked me, when we were rehearsing…we would stop in the middle of a piece and he would say “What were you doing right there?” and I would say, “I was just listening to you and playing.” He’d say, “No, but you have to really know what you’re doing. You have to think about what you’re doing, and know about how it works, what makes it work.”

So I thought about that afterwards. He was really right, because improvisation is very complex, it’s very difficult and emotionally draining. And the emotionally draining part of it takes you away from thinking about what it is that you’re doing technically. So from that point on I started really thinking about what it was that we were doing together. I know before I had met Ornette, this was, like, in 1956 in Los Angeles….I was playing with different jazz groups in Los Angeles, playing at jam sessions and jazz clubs….mostly bebop, and when it came time for the bass to solo, sometimes I felt that I didn’t want to play on the regular chord structure or the chord changes of the particular piece that we were playing. We might have been playing a standard tune or a blues or whatever. And sometimes I wanted to play on the feeling, or or the inspiration of the piece rather than the chord structure, um, and I was really not free to do that, because… when I tried to do that… the people that I was usually playing with were used to solos being played on the chord changes and they were used to knowing where the soloist was in the composition, and they wouldn’t know where I was if I would play on the way I felt about the piece, and when I did try, that was usually what would happen, a negative thing that would happen. The musicians would be…they wouldn’t know where I was in the piece, they would say “Hey, what are you doing?”

So I always held back from doing that until I met Ornette. And he was doing that. It was a way of life with him. That’s the way he improvised…was from the feeling of the piece, and creating his own chord structure spontaneously, anew, each time he played a composition, he would take his inspiration from that piece, or the feeling that he had for that piece…and he would create a new chord structure by a process of modulation, and intervals, phrasing, pitch and tonality.

Here’s a link to the complete Lecture-Demonstration. It’s fascinating reading and listening.

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Here’s some more music. How about “Farmer’s Trust,” a duet with Pat Metheney?

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Haden’s group Quartet West has produced a steady stream of wonderful albums, many reflecting the bassist’s love of songs and singers. Here’s a piece called “First Song.”

Quartet West: “First Song”

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

When asked about his playing, Charlie always gives respect to the tradition that started him out. He grew up in Oklahoma, playing “hillbilly” music with his family; he’s proud of his roots in bluegrass and country music (occasionally a bass solo in a free-jazz context will include quotes from “Old Joe Clark,” “Wildwood Flower,” or “My Home’s Across The Blue Ridge Mountains”) Recently he teamed up with some top acoustic players to make “Ramblin’ Boy,” a return to his country roots. In addition to an all star cast, the recording also features the harmony singing of his triplet daughters, Petra, Tanya and Rachel.

It’s a great record, and like much of his work, it conveys deep emotion and humanity through a seemingly effortless simplicity. Anyone with experience in music knows how hard that simplicity is to achieve. Here’s a link to an NPR piece on the project, with more music.

Despite having damaged vocal chords from a childhood bout with polio, Charlie was persuaded to sing for this record. Here’s his unaffected (but very affecting) version of “Shenandoah.”

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Tanya Haden is married to actor/musician Jack Black, who talks here about his father-in-law’s history and influence in music:

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Haden’s wide-ranging passions include many genres of Latin music.

Here he is with Gonzalo Rubalcaba (piano), Joe Lovano (sax), Federico Britos Ruiz (violin) and Ignacio Berroa (percussion), playing Artur Castro’s “En La Orilla Del Mundo.”

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

His two duet albums of African-American spirituals show him in intimate communion with the legendary jazz pianist Hank Jones. Both artists stay out of the way of these beautiful songs, embellishing tastefully but never grandstanding. The result is something sublime. (“Steal Away,” the first of the two, was one of the albums we had repeating during the long night and morning seven years ago when our daughter was born). Here’s “Wade In The Water.”

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

I could go on and on. But I’ll close with a track featuring the Quartet West and the Schleswig-Holstein Chamber Orchestra. This one’s called “There In A Dream.” Enjoy.

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Oh, and by the way, Charlie Haden just turned seventy-five a few weeks ago. Please join me in wishing him the happiest of happy birthdays — and let’s always keep working to bring about that better world his music makes us imagine.

Thanks for letting me share this.

Okay, that’s all.

Leave a Reply