India Indian music music Personal vocalists Warren's music

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

University of Southern Maine, May 5, 2023

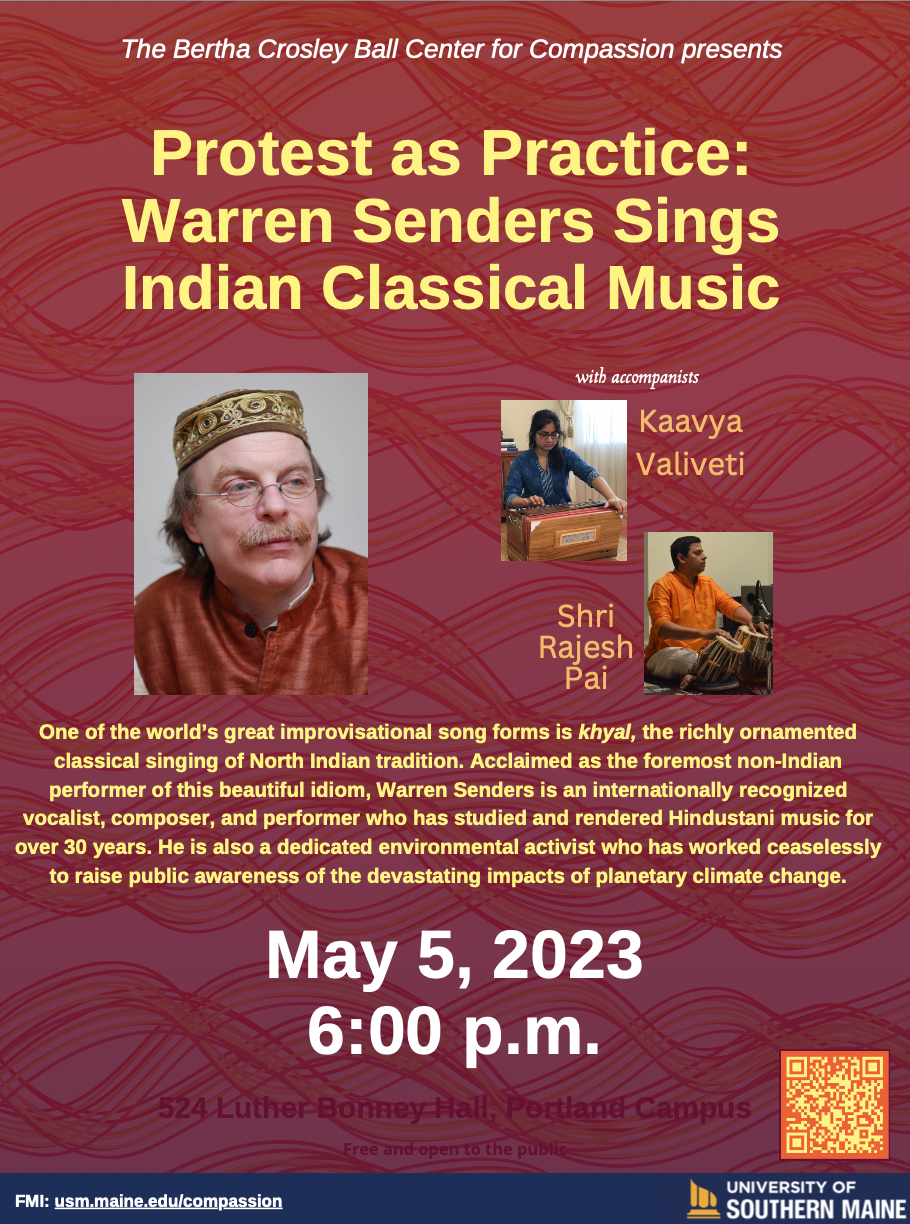

Earlier this year I gave my first public concert since before COVID. I had been invited to sing at the Bertha Crosley Ball Center for Compassion at the University of Southern Maine in Portland, and we wound up having a program almost concurrently with their Commencement.

Harmonium accompaniment was provided by Kaavya Valiveti and Rajesh Pai was on tabla. This was a very sympathetic team and I felt quite relaxed.

I opened with a full-length Puriya Kalyan. Vilambit: Hovana laagi saanjh / Drut: Jawoon tore charan.

The first half finished with one of my favorite light pieces, the Pahadi geet Jyuda kinjo dolna.

After the interval I started off with a two-parter in Hindol. The medium teentaal bandish Hori khelata hai giridhari is a great vehicle for bol-bant, and Rajesh and I got into some enjoyable rhythmic play. The drut composition Sundara aati chatur naar in ektaal has a very nice lilt.

The penultimate item was a tarana in Khamaj. This is an old traditional Gwalior cheez with some nice pakhawaj bols in the last line of the antara.

And I ended with Jamuna ke teer in Bhairavi.

I really enjoyed this concert. Though the audience was mostly newcomers to the music, they listened with great sympathy and feeling. There were several old friends there, including one person I’d last seen in 1976(!).

If for some reason you want to listen to the entire thing from beginning to end, with the introduction by Vaishali Mamgain and all of my remarks, here it is as a single uninterrupted file.

atheism environment Indian music Jazz music Personal vocalists Warren's music

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

“Singing The Long Now” — Concert Videos

The videos and sound recordings of the “Singing The Long Now” concert are now uploaded!

It was an extraordinary experience to prepare this material for performance, and to review it after the fact. Tufts University did a fine job with both audio and video, and I really enjoyed getting the pieces formatted and organized for this page. Please let me know your thoughts.

Needless to say, my most profound gratitude and love goes to the musicians:

Mimi Rabson — Violin, Voice

Helen Sherrah-Davies — Violin, Voice

Junko Fujiwara — ‘Cello, Voice

I’m presenting them all in order on this page, with some links to supplementary material as needed.

1. Hymn theme: “The Great Ocean Of Truth” / Raga Puriya Dhanashri: Alap, Khyal in 7 beats, Tarana in 12 beats.

Raga Puriya Dhanashri is usually meant for performance in the early evening. This suite of traditional Hindustani compositions is arranged for voice and string trio; the instrumental ensemble plays a redistribution of the standard accompaniment parts in support of vocal improvisation. The introductory alap is sung on open vowels and vocables, the medium-tempo khyal has a text in Braj (an archaic Hindi dialect) describing a scene from the life of Krishna, and the fast tarana is set entirely to non-lexical syllables.

2. A Hard Rain’s A-gonna Fall

Bob Dylan’s jeremiad is recomposed in Raga Mishra Dhani, the new melodic setting evoking both the apocalyptic surrealism of “Old Weird America” and the convoluted, polysemic language of the Urdu ghazal. The strings’ churning undercurrent hews to the basic 6-beat structure of the Hindustani Dadra taal, but can just as easily be heard as a group of rowdy country fiddlers.

3. “It’s Taken Me My Whole Life…”

This composition is built around the ritualized use of silence at different tempo levels. Every performer has a variety of pre-established melodic/rhythmic patterns, punctuated by extemporized “omissions” — this means that when (and how often) to be silent becomes the main focus of creative choice. Even segments of virtuoso free improvisation are built around the idea that the notes unplayed and unheard are the sweetest, the most expressive, the most crucial.

(Note: complete copies of the score and individual parts will be uploaded and posted within the next fortnight.)

4. Pete Seeger’s melodic setting of Malvina Reynolds’ lyrics (reflecting the words of the first astronauts to view our planet from space) is given a free rendering, with the strings providing a colotomic structure, timbrally aligned with the beautiful music of Sundanese tradition.

“From way up here, the Earth looks very small,

It’s just a little ball, of rock and sea and sand,

No bigger than my hand.

From way up here, the Earth looks very small,

They shouldn’t fight at all, down there,

Upon that little sphere.

Their time is short, a life is just a day,

You’d think they’d find a way,

You’d think they’d get along, and fill their sunlit days with song.

From way up here, the Earth is very small,

It’s just a little ball, so small,

So beautiful and dear.

Their time is short, a life is just a day,

Must be some better way,

To use the time that runs, among the distant suns.

From way up here.”

5. Man With Sign — For Speaking/Singing Voice and String Trio

A reading from my ongoing intersectional activism/performance project, now in its seventy-fourth week of rush hour mornings at Medford’s Roosevelt Circle.

6. “This Is A Composition Which Concerns Itself With Timescale”

Like Paris’ Centre Pompidou, this composition for intoning voices and instruments wears its infrastructure on the outside. To say anything more in these notes would be redundant, except to note that the complete texts of the spoken parts can be found here.

7. The Spider’s Web

E.B. White’s words, Pete Seeger’s melody — my arrangement of this love song is a kind of “folk minimalism,” using asynchronous repetition of simple melodic phrases to create background textures that allow the melodic line and its meaning to unfold.

“The spider dropping down from twig, unfolds a plan of her devising:

A thin, premeditated rig, to use in rising.

And on this journey down through space, all cool descent and loyal-hearted,

She builds a ladder to the place, from where she started.

Thus I, gone forth as spiders do, in spider’s web a truth discerning,

Attach one silken strand to you, for my returning.”

8. The great jazz innovator Ornette Coleman once remarked, “I wish people would play my tunes with different changes every time, so there would be all the more variety in the performance.” Whenever we approach Ornette’s music, we try to keep this in mind.

“What reason could I give to live?

Only that I love you.

How many times must I die for love?

Only when I’m without you.

Where will the world be, if not in the sky when I die?

What reason could I give to live?

Only that I love you.”

9. Ancient Light / Ab Hone Lagyo

A meditation on time, trees, and light — followed by a thumri composition in the morning raga Kalingda. Set to the slow 16-beat chachar tala, this song in Braj extols the beauty of the new morning light, the songs of birds, the effulgence of opening blossoms — a tender, optimistic meditation on possibility and the inevitability of rebirth.

10. The title of this piece references one famous quote from Isaac Newton, and the text is another equally well-known remark from the great scientist (here altered slightly in the interest of gender equity). The words are set to three different eleven-beat structures in medium, fast, and slow tempi.

“I don’t know what I may seem to the world, but as to myself I seem like a child playing on the seashore / diverting myself, now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell / while the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.”

Education music Personal Warren's music: sources temporacy temporal literacy Warren's music

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Texts for “This Is A Composition Which Concerns Itself With Timescale”

These are the texts used in the February 5 performance of “This Is A Composition Which Concerns Itself With Timescale.”

Details of the performance structure will be posted in the next couple of weeks as I get materials uploaded.

LUCA, an acronym for the last universal common ancestor, probably dates to around 3.8 billion years ago. At that time, LUCA was bobbing around on ocean waves with neither worries nor neighbors. Our human ancestors differentiated from other living beings about one billion years ago. About four hundred million years ago, the earliest froglike beings developed joints on their pectoral and pelvic fins and slithered out of the sea onto land.

About 1.8 million years ago, our African ancestors moved North into the Caucasus and slowly spread out across what is now Europe and Asia. Roughly forty thousand years ago, people crossed what we call the Bering Sea into the great landmass of the Northern hemisphere. Almost one thousand years ago, Europeans built small boats and sailed across unknown oceans toward an unknown land.

Mary Pipher — The Green Boat pp 188-189

The destiny of our species is shaped by the imperatives of survival on six distinct time scales. To survive means to compete successfully on all six time scales. But the unit of survival is different at each of the six time scales. On a time scale of years, the unit is the individual. On a time scale of decades, the unit is the family. On a time scale of centuries, the unit is the tribe or nation. On a time scale of millennia, the unit is the culture. On a time scale of tens of millennia, the unit is the species. On a time scale of eons, the unit is the whole web of life on our planet. Every human being is the product of adaptation to the demands of all six time scales. That is why conflicting loyalties are deep in our nature. In order to survive, we have needed to be loyal to ourselves, to our families, to our tribes, to our cultures, to our species, to our planet. If our psychological impulses are complicated, it is because they were shaped by complicated and conflicting demands.

The earliest known trade routes in regular use crisscrossed eastern Europe about 30,000 years ago, distributing prefashioned blanks of flint from mines in Poland and Czechoslovakia over a wide area. It was in eastern Europe, too, that the oldest ceramic objects yet discovered were made, [including] models of animals and…a ceramic “Venus” — a stylized figurine of a woman…this European site, shared by more than a hundred people, affords the eariest evidence of a quantum jump in the sizes of human groups and the advent of the first communities larger than family bands.

Nigel Calder — Timescale, p. 159

A huge colony of the sea grass Posidonia oceanica in the Mediterranean Sea could be up to one hundred thousand years old.

(wikipedia)

An attosecond is 1 times 10- to-the-minus-eighteenth — one quintillionth — of a second.

It is the time it takes for light to travel the length of two hydrogen atoms.

An attosecond is to a second what a second is to about 32 billion years.

(wikipedia)

In hillside caves of southwestern Germany, archaeologists have uncovered the beginnings of music and art by early modern humans. .. New evidence shows that these oldest known musical instruments in the world, flutes made of bird bone and mammoth ivory, are even older than first thought.

Animal bones found with the flutes were 42 to 43,000 years old, [dating them to] around the time the first anatomically modern humans spread into Central Europe… along the Danube River valley.

If we imagine ourselves living in New England in the 1700s, and we then imagine ourselves looking from that vantage point into the future, does the rural landscape as we now know it seem unattractive because it no longer looks like it did when Queen Anne ruled the colonies? Would a longer step back to the 1500s make us protest the Spanish introduction of culture-changing horses to this continent? And would a step even farther back in time make us mourn the arrival of the first Stone Age humans who would slaughter the American mammoths and mastodons and thus leave our landscapes unnaturally silent — but much safer to walk in?

Curt Stager — Deep Future

Two-hundred and fifty million year-old bacteria, Bacillus permians, were revived from stasis after being found in sodium chloride crystals in a cavern in New Mexico.

Having survived for 250 million years, it is the oldest living thing ever recorded.

(wikipedia)

A visit to a Pleistocene cave in southern France reveals the past in subtle ways. Paintings on the cave walls and ceiling show a pack of wild horses galloping along a ledge, while vivid antlered reindeer leap toward the viewer from nearby walls. Bison scratched into stone show fine-line features of nostrils, eyes, and hair. Big- bellied horses lope toward us on short legs.

Some prehistoric master saw the essence of these animals embedded in the chance curves of the cave, [and] called them forth to the eye, using negative space in ways we do not witness again until the work of the sixteenth century.

These signals across tens of millennia carry a heady sense of graceful intelligence. We know well enough what animals lived then, but only in such paintings can we delve into the cerebral wealth of our ancestors…These paintings… are the best sort of deep time messages, conveying wordless mastery and penetrating sensitivity across myriad millennia and staggeringly different cultures.

Gregory Benford — Deep Time, p. 202

The galactic year, also known as a cosmic year, is the duration of time required for the Solar System to orbit once around the center of the Milky Way Galaxy. Estimates of the length of one orbit range from 225 to 250 million terrestrial years.

(wikipedia)

Biologists track the extinction of whole genera, and in the random progressions of evolution feel the pace of change that looks beyond the level of mere species such as ours. Darwinism invokes cumulative changes that can act quickly on insects, while mammals take millions of decades to alter. Our own evolution has tuned our sense of probabilities to work within a narrow lifetime, blinding us to the slow sway of long biological time.

Gregory Benford — “Deep Time”

One day in the life of Brahma is called a Kalpa, and lasts 4.32 billion years. Every Kalpa, Brahma creates 14 Manus, who in turn manifest and regulate this world.

Each Manu perishes at the end of his life, and Brahma creates the next. The cycle continues until all fourteen Manus, and the Universe, perish at the end of Bramha’s day. Then Brahma sleeps for a period of 4.32 billion years. The next ‘morning’, Brahma creates fourteen Manus in sequence, just as he has done on the previous ‘day’.

This cycle continues for 100 ‘divine years’ at the end of which Brahma perishes and is regenerated. Brahma’s entire life equals 311 trillion, 40 billion years.

Once Brahma dies there is an equal period of unmanifestation for 311 trillion, 40 billion years, until the next Brahma is created.

(wikipedia)

Jiahu was a Neolithic settlement in the central plain of ancient China, near the Yellow River. Settled around 7000 BC, the site was flooded and abandoned around 5700 BC.

Among the discoveries at Jiahu were playable flutes made from the wing bones of the Red- Crowned crane, tuned to the pentatonic scale.

(source)

Consider…a coniferous forest. The hierarchy in scale of pine needle, tree crown, patch, stand, whole forest, and biome is also a time hierarchy. The needle changes within a year, the tree crown over several years, the patch over many decades, the stand over a couple of centuries, the forest over a thousand years, and the biome over ten thousand years. The range of what the needle may do is constrained by the tree crown, which is constrained by the patch and stand, which are controlled by the forest, which is controlled by the biome.

Stewart Brand — Clock Of The Long Now, p. 34

We are ever restless, we hominids. It is difficult to see what would finally still our ambitions — neither the stars, nor our individual deaths, would ultimately form a lasting barrier. The impulse to push further, to live longer, to hourney farther — and to leave messages for those who follow us, when we inevitably falter and fall — these will perhaps be our most enduring features.

Still we know that all our gestures at immortality — as individuals or even as a lordly species — shall at best persist for centuries or, with luck, a few millennia. But ultimately they shall fail.

Intelligence may even last to see the guttering out of the last smoldering red suns, many tens of billions of years hence. It may find a way to duddle closer to the dwindling sources of warmth in a iuniverse that now seems to be ever-expanding, and cooling as it goes. Whether intelligence can persist against this final challenge, fighting the ebb tide of creeping entropy, we do not know.

But humans will have vanished long before such a distant waning. That is our tragedy. Knowing this, still we try, in our long twilight struggles against the fall of night. That is our peculiar glory.

Gregory Benford — “Deep Time”

humor India Indian music music Personal vocalists: dagarel doggerel

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Comic Verse About Indian Music, part 2

“Oral Tradition: Some Hidden Aspects — or, The Ustad’s Advice.”

When I was in my early days,

I fell in love with raags,

Though my mother said the singers

Sounded more like frogs.I learned to sing the alap,

I learned to sing the cheez,

My taan became proficient,

But still it failed to please.I asked an ancient ustad,

how to make a lovely note.

“My son,” he said, “it just requires

a clearing of the throat.”“You start down in the glottis,

and gargle up some phlegm,

then bring it through your larynx

for a truly great ACC-HEM!”“My son,” he then continued,

“Your music won’t be great, ’till

You can make a wad of mucus,

Stained red from years of betel.”I listened to the records

Of the pandits and ustads;

’twas true, I found: the greatest singers

Made the biggest wads.When Bade Ghulam Ali Khan

Throws all his weight around,

His taans, alaps, and gamaks

Produce a stirring sound.But he’s got something else, my friends,

Which modern singers lack:

A wonderfully resonating way

of going “Aaaaaaak!”I heard the maestro Faiyaaz Khan,

who sang in days of yore:

He’d scrape his learned larynx,

and bring up more…and more.Paluskar’s hack was beautiful,

And likewise Amir Khan…

But now this great tradition,

it seems cannot go on.The modern crowd of singers

Will stay forever small,

For though they may sing sweetly,

They cannot cough at all.

humor India Indian music music Personal: dagarel doggerel

by Warren

2 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

An Obscure Genre: Comic Verse About Indian Classical Music, part 1.

“Intonational Variation in Oral Tradition — or, Tutti Shruti”

In bygone days in India, the emperor Akbar

Had in his court a singer who was known both near and far.He had a wondrous repertoire, there was no doubt of that —

But every note in every raga came out slightly flat.Because his voice was out of tune, they called him Besur Khan,

He founded a tradition, so his gayaki lives on.For he had some disciples, and they disciples too —

And all of them sing ragas in a loud, discordant moo.And if you ask them nowadays, “why do you sing so flat?”

They’ll say, “it’s our gharana.”

That’s all there is to that.

India Indian music music Personal vocalists Warren's music: fundraising khyal

by Warren

4 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Making It Happen!

The Beauty of Khyal — A Recital of Night Ragas

I’m as happy with this recording as I’ve ever been. The recording session we did on August 16 of this year was wonderfully productive, and this CD represents the first installment of the raga performances Milind Pote, Chaitanya Kunte, and I laid down that night.

Please pitch in. You’ll love this music.

India Indian music music Personal vocalists Warren's music

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Bandra Concert, August 21, 2013

The music this evening was just gorgeous. Mukta Raste’s beautiful theka was inspiring and supportive, and Ravindra Lomate played excellent sangat on harmonium. The Bandra Base is a once-in-a-lifetime room: small, sympathetic, filled with excellent resonance and history. Dee Wood, proprietor of the Base, made the farmaish for Malkauns. I’m glad he did; this performance came out with lots of bhaav.

Mora bolere – vilambit teentaal

Banwari mori manata nahin – drut teentaal

Tarana – drut teentaal

Warren Senders – voice

Mukta Raste – tabla

Ravindra Lomate – harmonium

August 21, 2013

The Bandra Base, Bandra, Mumbai, India

Peer na jaanire – vilambit ektaal

Man man ab to man – drut ektaal

tarana – drut teentaal

Warren Senders – voice

Mukta Raste – tabla

Ravindra Lomate – harmonium

August 21, 2013

The Bandra Base, Bandra, Mumbai, India

music Personal Warren's music

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Yes, No, Maybe? (Trombone Duet)

This trombone duet was composed out of a need to write more music for trombone, because trombones are awesome. I was very fortunate to have Bob Pilkington and Jim Messbauer doing this version of the piece. There’s another performance from a JCA concert with Pilkington and David Harris; I’m going to try and find that and upload it too, to facilitate side-by-side comparisons for all you trombone geeks out there.

Indian music music Personal Warren's music

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Horn Gamelan (1990)

Back in my college days, I began working on a piece which would employ my very rudimentary understanding of gamelan structure to a brass ensemble. I worked on “Horn Gamelan” for a long time, filling in hundreds of teeny-tiny notes on a big folder of score paper, then copying out all the parts by hand. There were five sections, all timbrally more or less identical. The piece was performed in 1981 at a concert I produced at Boston’s Studio Red Top, a performance space run by Cathy Lee. That evening was a sort of “graduation recital” for my final year at Campus-Free-College (Beacon College).

For a long time after that the score lay dormant. In 1990 I was awarded a little grant from Meet The Composer, and part of it allowed me to resurrect Horn Gamelan. I picked the two best movements, wrote a fanfare/introduction (which included a sitar improvisation by my wife Vijaya) and an interlude which evoked some of the timbres of Sundanese music, and had a nice performance that evening. Somewhere I have a videotape of it…wish I could find it!

Here is the recording of my revised “Horn Gamelan” from its 1990 performance. Hope you enjoy it!

India Indian music music Personal Warren's music

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Interstices – String Quartet (composed 1984, performed 1993)

“Interstices” had its origin in a chart I wrote for the first incarnation of Antigravity, which included all the basic ingredients: a seven-beat vamp, a twisted melody in a Phrygian Maj7 scale, and the superimposition of 6-beat groups on the 7-beat structure to create a 42-beat cross-rhythm. But I feel that the full realization of these ideas was only made possible by the quartet format.

I composed the string quartet score of “Interstices” in 1984 on a visit to New Paltz, NY. The project was originally undertaken as a project for Mimi Rabson’s R.E.S.Q. (Really Eclectic String Quartet), which played it in a recording session before I left for India the first time in 1985.

The version for RESQ was through-composed for their unusual orchestration of 3 violins and bass. Their version sounded great and was the only recorded rendition for many years. In 1990 I assembled a “New Ensemble Music” concert and prepared the piece for performance by 2 violins, viola, and bass — but the woman who was to play 2nd violin disappeared 10 days before the concert and never returned, and it wound up being performed as a trio.

In 1993 I put together another “New Ensemble Music” concert, and this time I got lucky. John Styklunas was playing bass, and he brought his colleague Steve Garrett in on ‘cello; I rewrote the viola part for ‘cello, and I think it sounds great that way. Teresa Marrin and Tomoko Iwamoto did a great job on both violins. There is no distinction between first and second fiddles in terms of the complexity or ranking of the parts.